A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Will Murray asks, ‘Do Lost Raymond Chandler Stories Exist?’

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.

– Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

Will Murray makes a return to A (Black) Gat in the Hand. Last month, Strand Magazine (who I wrote DVD reviews for in a prior century) published a lost Raymond Chandler story. Which got Will to thinking…

The recent discovery of a previously unknown and unpublished short story by Raymond Chandler reminded me of a question that’s lingered in my mind for a very long time.

How did Chandler in the early years the Depression support himself and his wife writing for Black Mask and other titles when he only sold a two or three stories a year?

Black Mask was then paying only a penny or a penny and a half a word for fiction to any but their top writers. Chandler was writing stories that were roughly 12 to 18,000 words long. He received $180.00 for his first sale, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot.“ Even considering what a penny could buy in 1933, when a loaf of sliced bread cost 3 cents, Chandler wouldn’t have been able to survive solely writing for Black Mask.

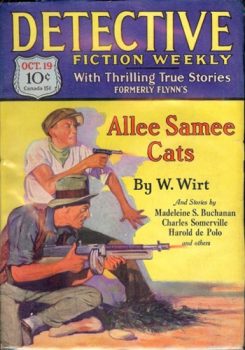

It wasn’t until 1935 that he broke into Munsey’s Detective Fiction Weekly, which probably paid him two cents a word, and possibly more. A considerable raise, but still far short of what was required for subsistence living. And he only sold one story to DFW, “Noon Street Nemesis.“

Since Chandler had been a well-paid oil company executive until he lost his job in 1932, conceivably his savings carried him for some period. But according to Chandler biographer Tom Hiney, by the time he started working on “Blackmailers,“ Chandler’s savings had been all but exhausted. The story took him five months to write. Add another month or so until he received the acceptance check. So that’s $30.00 a month for six months toil, paid at the end of the six-month period. At his old executive position, Chandler’s salary had approached $10,000 a year.

As Chandler himself once admitted, “I wrote pulp stories with as much care as slick stories. It was very poor pay for the work I put into them.“

As Chandler himself once admitted, “I wrote pulp stories with as much care as slick stories. It was very poor pay for the work I put into them.“

During this period, Chandler received $100.00 a month for helping the plaintiff in a lawsuit against his old employer, which was intended to keep him financially above water while he broke into the field of writing. But that could not have lasted long. According to biographer Tom Williams, the Chandlers eked out a bare subsistence living on $25.00 a week.

Over time, his Black Mask word-rate rose to five cents a word. It’s estimated he earned on average $1,000 a year during the mid-to-late 1930s, and sometimes a few hundred dollars more.

Would Chandler’s annual pulp magazine sales have carried him clear up to 1939-40, when he broke into hardcover print?

I have my doubts.

There’s an aside in the newly discovered Chandler story, “Nightmare,” directed to his wife: “This will remind me of the days when I used to get returned manuscripts.” This appears to contradict Chandler’s assertion that he sold the first story he ever wrote and landed every submission thereafter.

Of course, editor Joe Shaw was infamous for sending stories back to be rewritten according to his exacting standards. So that might account for some of that. And the story that landed in DFW might have been a BM reject.

I have noticed some Black Mask writers popping up in obscure pulp magazines, what were back then called “dump market” magazines––low paying periodicals where seasoned professionals sent their rejects after higher paying magazines refused them.

One would think that the industrious Chandler would have encountered a few outright rejections and availed himself of the opportunity to submit them elsewhere.

However, some pulp writers tore up their rejects, either because an editor savaged them, or in the mistaken belief a reject meant it was worthless.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

There are many known examples––and no doubt, a great many more unknown ones––of stories that were rejected for reasons that have nothing to do with their inherent quality.

In the 1930s, in an effort to strengthen their brands, magazines tended to slant and specialize to a greater degree than they had in the previous decade. Some editors went so far as to exclude women characters––or at least significant women characters––from their pages. A perfectly good story violating that unexpressed taboo was summarily rejected.

One pulp writer had a story bounce back for reasons other than its merits. In his rejection letter, the editor explained that he was very close to buying the story when a better manuscript of its type happened to land on his desk. He took the one by the presumably better-known author.

The fact that the “reject” was on the verge of being accepted indicates there was nothing fundamentally wrong with it. The manuscript was perfectly publishable. It simply fell victim to unfortunate timing.

A baffled Western pulp writer once received an editorial response stating how wonderful his submission was. Then came the “but…“

In my book, Wordslingers: an Epitaph for the Western, I quoted writer Stephen Payne about another such an editorial blind spot.

“In other quarters it was carried to the point of ridiculousness, as witness an editor speaking: ‘Our staff had agreed that this story was a “must” for our book before they passed it on to me. I liked it, too, and was about to okay it when I suddenly discovered it didn’t fit our formula. So of course I had to reject it.’”

This was hardly an unusual occurrence. Taboos from No Snakes to No Sex abounded in the pulps, but lesser taboos were specific to certain pulp houses. Fiction House wouldn’t accept yarns laid in a jungle––any jungle. For years, the Thrilling Group wouldn’t allow Jewish character to appear in the pages of their magazines––despite the fact that most of their editors were Jewish!

Chandler’s byline does not regularly appear outside of Black Mask until the year 1937, when he jumped ship to Dime Detective after Joe Shaw left Black Mask. But seasoned professionals, knowing that editors looked askance at their top writers selling to cheaper magazines, especially if they were rival magazines, would understand that the best course of action would be to sell those rejects under pseudonyms not connected to the actual author.

If Chandler did this, no one living knows anything about it. No record of any such sales survive. If they ever existed.

If Chandler did this, no one living knows anything about it. No record of any such sales survive. If they ever existed.

But since so few Chandler short stories and novels exist, it’s a tantalizing thought that buried in the back pages of some obscure detective pulp might be found cast-off Raymond Chandler pieces.

I am reminded of a conversation I had with Jack Schiff of the Standard Magazines, otherwise known as the Thrilling Group, at a Pulpcon back in the early 80s. We were sitting in the hotel lobby and Jack started to tell a story about a writer whom they published under one of their house names, or perhaps it was a pseudonym, I don’t recall. He said it would amaze modern readers to know who it was.

In the middle of the telling the story, Schiff caught himself and remarked something to the effect that it probably was best that he kept that secret.

I didn’t try to pry it out of him. But I remember that at the time the name Raymond Chandler popped into my head because there were so few writers who might write for the magazines he co-edited, such as Thrilling Detective, whose identity might be so relevant that 50 years later Schiff thought he should keep mum about it.

Schiff was one of the group of sub-editors that included Mort Weisinger, Donald Bayne Hobart, Bernard Breslauer, and others who worked under Standard Magazine‘s editor-in-chief, Leo Margulies. Standard, which started early in the Depression, grew to be a powerful chain of pulp magazines during the following decades.

They had some editorial peculiarities. Some of which writer Howard Wandrei (brother to Donald Wandrei) detailed in a letter to his father back in Minnesota during the period where Howard was writing for various pulp magazines ranging from Munsey’s Detective Fiction Weekly to the Spicy group. The letter is dated June 21, 1935. Here is a revealing excerpt:

According to [Weisinger’s] statement, the market is a great, gawping maw, and for God’s sake why don’t we send in some stories or else the gang at the office has to write the damned things themselves. As a matter of fact, the market is wide open at the present time for anything at all good. The local boy could be making good right now, but even fair stories, unfortunately, can be turned out only at a certain speed. I am working as fast as I can. Weis. said that all the good stories go to Munsey‘s first, next to S&S, third to Standard. Still, I am somewhat surprised to have a man request me for stories that he knows another company has rejected. Further complication in that Standard will pay Don and me 1 cent when they re-write yarns, or use them straight under their cover or house name (Scanlon), and one and a half cents when their own names are used.

Standard will buy as many stories as we can produce, in lots up to twenty, payable on acceptance. Each story need only be a who-done-it, which is to say the presentation of murder, the introduction of suspects, the settlement of guilt on a rather unsuspected person. This is routine, not writing, but you can see how desperately in need some of these editors are. The magazines in that group must have between eighteen and thirty stories before the end of next week, or the staff must do them. They make out checks every Friday afternoon. […] Their system is as follows: an ms. arrives in the office. Someone picks it up and reads it and writes a comment on it, to wit: “Lousy.” “Fair.” “Good.” “Phooey.” “Swell.” “Tear- jerker.” “No.“ You get the idea. If the story gets two bad comments, it’s rejected. If two good, sale.

They claim that if any ms. has anything in it that is likable, they’ll rewrite it themselves to suit the mag and buy it. The outfit is positively cuckoo.

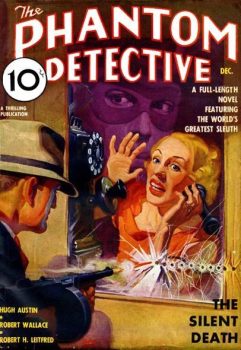

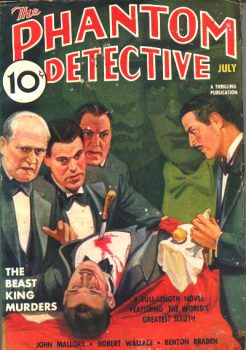

Schiff was one of the sub-editors whose job it was to take a rejected manuscript and whip it into shape so it was publishable. They did it with everything from their lead novels in Thrilling Detective and Popular Detective to back-of-the-book stories in The Phantom Detective.

Lester Dent once sold a flock of his rejects to Margulies, putting a pen name he had used at another pulp house, Cliff Howe. Unbeknownst to Dent, the original publisher had appropriated that byline, turning into a house name.

Margulies ran Dent’s rejects under his company’s own house names, Robert Wallace and C. K. M. Scanlon. These bylines appeared so often in the Thrilling magazines they were virtually ubiquitous for some twenty years.

I once happened upon one series character, who ran in back pages of The Phantom Detective, where the byline on one story was C.K.M. Scanlon, but in follow up story, the real author was revealed to be Leonard B. Rosborough––proving that Standard editors slapped their house names on stories without consideration for the writer.

I once happened upon one series character, who ran in back pages of The Phantom Detective, where the byline on one story was C.K.M. Scanlon, but in follow up story, the real author was revealed to be Leonard B. Rosborough––proving that Standard editors slapped their house names on stories without consideration for the writer.

It may be far-fetched, but it’s probably not out of the realm that some of the Thrilling pulps printed stories by rather well-known authors who sold their cast-offs to Margulies, who then tossed them to his so-called “trained sealed” editors to polish and fix and repair until they were passable and publishable.

Unfortunately, the payment records for the Thrilling group were trashed long ago. And manuscripts revised in-house might have been reworked from first sentence to final paragraph, making detection of a specific author’s style difficult.

One of the sub-editors at Thrilling, Samuel Mines, once told me that they were very formulaic with their lead character novels. They insisted something like eight elements that had to be present in chapter 1. And if those required elements weren’t in the author’s original manuscript, one of the trained seals would rewrite that opening chapter to include them–-sometimes from scratch.

Mines sold a lead novel to one of their western titles, Range Riders. When he read it in print, he discovered that several chapters were completely rewritten and otherwise altered. I believe the first chapter was one of them.

Consequently, the homogenized product the Thrilling group published was often a collaboration between the original author and one of several sub–editors.

Finding traces of the original author can be difficult. I detected the certain stylistics of Norvell Page of Spider magazine fame in one Phantom Detective novel, Death Glow, but the first chapter was the work of an entirely different writer––no doubt one of Margulies’ trained seals.

And of course, there were other lesser short-lived dump markets. The early Black Book Detective, Super–Detective Stories, and many others. Some of these are so rare that picking through them for hints of a recognizable style would be a bibliographic challenge, not to mention a fool’s quest.

I’m reminded of the story Orson Welles told of selling pulp stories in collaboration with another writer whose name he did not recall, when he lived in Spain and Africa circa 1933. He had no recollection of the details other than that one series involved a “rich, aristocratic sleuth living with his three elderly aunts in Baltimore” and they produced “a good deal of science fiction of the Lobster-Men type.” Other stories were laid in the Far East, and a few landed in the top-flight Adventure.

Welles vaguely remembered the name Clayton in reference to these stories, which has caused confusion.

Some thought he might be referring to William Clayton, who published a powerful pulp chain until the Depression killed it in 1933. Clayton published Astounding Stories until 1933, which dovetails with the Lobster-Men reference––except that the authors who appeared in its pages were largely known quantities. A Frederick Clayton was the editor of Argosy in 1934-36, which falls close to the 1933 timeframe when Welles was in Europe. But neither of those individuals appear to be the Clayton Welles invoked.

Specifically, Welles stated that his collaborator was named Clayton. One of Welles’ Chicago friends of that era was John Clayton, former foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune who started writing radio drama for WLS in 1933. He is a strong suspect, having lost his newspaper job prior to that year. Welles stated that these collaborations appeared under the other writer’s noms de plume, and that Welles did wrote pulp for the better part of a year.

But finding those stories may also be too much of a challenge to undertake since it would require a systematic review of magazines that are not easily accessible as a group. Never mind the fact that Welles never saw this series in pouring and we might assume some never sold.

Which brings us back to Raymond Chandler.

Fundamentally, the inescapable and unsolvable problem of searching for pseudonymous Raymond Chandler stories in the pages of 1930s pulp magazines is that we don’t know with any certainty such ephemera actually exists. And since you can’t prove a negative, even a comprehensive search conducted by a discerning investigator and possibly backed by artificial intelligence analysis might be ultimately pointless.

Still, it couldn’t hurt to try….

If one were to go looking for pseudonymous Chandler stories in the 1930s pulp detective magazines, one would start with the usual dodges writers often employed to coin pseudonyms.

I started with Chandler’s middle name, Thornton, but that only led me to a single appearance in Real Detective, January 1933, Jack Thornton’s “Death Throws the Dice!” But it’s an article, not a short story. Not much to go on there. Since it predates Chandler’s first pulp sale, we can more than likely dismiss it.

Other inquiries using mother’s maiden name (Dart), wife’s maiden name (Pascal), produced nothing tangible.

While mulling over this problem, I remembered a byline scattered through the detective pulps of that decade that has long intrigued me: John Mallory.

Mallory was the protagonist of Chandler’s first two Black Mask stories. He was never given a first name. Chandler abandoned the character in 1933, with “Smart-Aleck Kill.”

So I looked up John Mallory in the online FictionMags Index. What I found was intriguing.

Between 1935 and 1938, that byline appears in an even dozen detective magazines, beginning with a quartet in Super–Detective Stories before it folded.

(An Arthur Mallory also appeared once in Super–Detective, but that was a known pseudonym of Ernst M. Poate, who had a story under his own name in the issue containing that solitary Arthur Mallory story.)

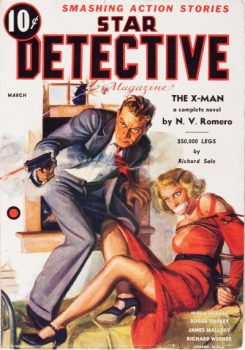

Most of the rest were printed in Thrilling Detective and Popular Detective, which Jack Schiff co-edited. A few ran in bottom-of-the-barrel titles such as Martin Goodman’s Star Detective Magazine and Associated Authors’ Detective and Murder Mysteries.

Titles like “Murder Pay-Off,” “Dead Center Murder,” “Five Grand Kill,” and “Smart Guy” don’t tell us very much on the face of it. All were short stories. Mallory produced no novelettes.

Titles like “Murder Pay-Off,” “Dead Center Murder,” “Five Grand Kill,” and “Smart Guy” don’t tell us very much on the face of it. All were short stories. Mallory produced no novelettes.

After a three-year hiatus, in 1941, John Mallory pops up for a final appearance, “Extra Service,” in Detective Fiction Weekly. Coincidentally or not, 1941 was the year Chandler made his only sale to Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine. This was after Chandler was absent from the detective pulps of two years. Suspiciously parallel, but not evidential. By 1940, one would think Chandler’s byline would have sold any story for a far more princely sum than John Mallory would have fetched. And DWF was no downriver half-penny pulp market, but a top title in its field.

Circumstantially, we have here a reasonable ground for inquiry. The chronology of Mallory’s pulp career is strikingly parallel to that of Chandler’s. Chandler rarely wrote outside of the detective field, and Mallory never did. If Chandler were to coin a pen name, evoking the protagonist of the story that launched his career is exactly the kind of sly gimmick pulp writers favored. It all tracks. Except for conclusive proof.

And at a penny a word, or less, those dozen mid-1930s stories would have made a significant difference in the Chandlers eating regularly. If only.

I happen to have one John Mallory story available to me. “Pushover,” in the July 1937 issue of The Phantom Detective. So I read it.

Detective-Sergeant Ken Fortune is the lead character, not one of Chandler’s usual private eyes. Not a promising start.

The early pages read exactly like any number of short stories that ran in the back of Standard’s detective magazines. There was no strong suggestion of a style beyond the familiar Thrilling house style.

Deeper into the text, I detected flashes of semi-poetic hard-boiled Chandleresque touches. Here are two examples:

‘Fortune felt the bottom of things letting go. His hunch, which had seemed so hot in Livy’s, was now as dead as last night’s newspaper.’

‘Forked lightning was tame beside Fortune’s gun draw. He shot without aiming, without thinking. Door glass rattled with the explosion.The bodyguard’s nose disappeared and crawling blood took its place as he landed in the corridor. Slick’s gun went off, jumping. The bullet tore Fortune’s .38 from his fingers, flinging it across the room. Shock sizzled up his arm—a monstrous sense of utter defeat followed.’

I was not persuaded. By 1937, virtually every pulpster producing detective fiction was emulating the prevailing hard-boiled style as exemplified by Dashiell Hammett, Chandler and other Black Mask regulars. I found nothing conclusive, nothing that would make me jump up and proclaim, “That sounds exactly like Raymond Chandler!”

Perhaps an examination of other John Mallory stories not worked over by Standard editors might reveal something different. But let’s not get our hopes up. Lost Raymond Chandler stories many be a pulp chimera, nothing more.

Yet all these decades later, I still wonder about the famous author Jack Schiff had been about to reveal to me….

Hey! Do you suppose it might have been Orson Welles?

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2025 (10)

Shelfie – Dashiell Hammett

Shelfie – Dashiell Hammett

Windy City Pulp & Paper Fest – 2025

Will Murray on Who was N.V. Romero?

Conan – The Phoenix in the Sword in Weird Tales

More of Robert E. Howard’s Kirby O’Donnell

More Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard – Conrad and Kirowan

Hardboiled Gaming- LA Noire

Western Noir: Hell on Wheels

T.T. Flynn’s Mr Maddox

Dashiell Hammettt’s The Scorched Face (my intro)

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2024 Series (11)

Will Murray on Dashiell Hammett’s Elusive Glass Key

Ya Gotta Ask – Reprise

Rex Stout’s “The Mother of Invention”

Dime Detective, August, 1941

John D. MacDonald’s “Ring Around the Readhead”

Harboiled Manila – Raoul Whitfield’s Jo Gar

7 Upcoming A (Black) Gat in the Hand Attractions

Paul Cain’s Fast One (my intro)

Dashiell Hammett – The Girl with the Silver Eyes (my intro)

Richard Demming’s Manville Moon

More Thrilling Adventures from REH

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (15)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery (my intro)

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams

T,T, Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part II

William Patrick Murray on Supernatural Westerns, and Crossing Genres

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘Getting Away With Murder (And ‘A Black (Gat)’ turns 100!)

James Reasoner on Robert E. Howard’s Trail Towns of the old West

Frank Schildiner on Solomon Kane

Paul Bishop on The Fists of Robert E. Howard

John Lawrence’s Cass Blue

Dave Hardy on REH’s El Borak

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (7 )

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (21)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Phantom Crook (Ed Jenkins)

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘The Shrieking Skeleton’

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

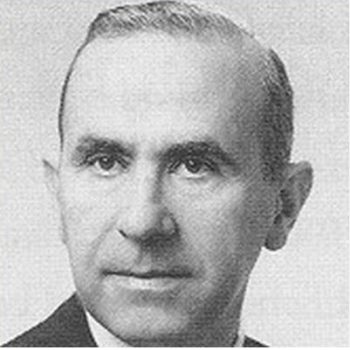

There are some outstanding names in the ‘New Pulp’ field, but William Patrick Murray’s probably stands above them all. Along with Doc Savage, Will has written Tarzan and The Spider. And he’s quite the Sherlock Holmes writer. Short stories, comic books, radio plays, nonfiction essays and books – Murray has done it all. He created The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl for Marvel Comics, and his collection of essays on Doc Savage, Writings in Bronze, is a must read. I love a good book introduction, and Murray has written some fine ones for Steeger Books. Visit his website Adventures in Bronze.

There are some outstanding names in the ‘New Pulp’ field, but William Patrick Murray’s probably stands above them all. Along with Doc Savage, Will has written Tarzan and The Spider. And he’s quite the Sherlock Holmes writer. Short stories, comic books, radio plays, nonfiction essays and books – Murray has done it all. He created The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl for Marvel Comics, and his collection of essays on Doc Savage, Writings in Bronze, is a must read. I love a good book introduction, and Murray has written some fine ones for Steeger Books. Visit his website Adventures in Bronze.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, and founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

You can definitely ‘experience the Bobness’ at Jason Waltz’s ’24? in 42′ podcast.

[…] (Black Gate): The recent discovery of a previously unknown and unpublished short story by Raymond Chandler […]