A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask‘s Cap Shaw on Writing

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

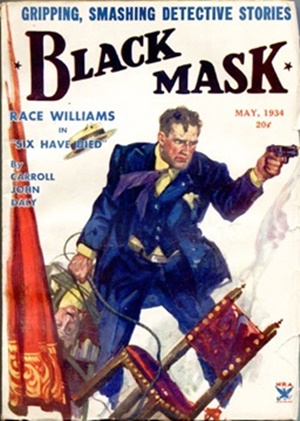

The hardboiled school was born in the page of Black Mask Magazine under the editorship of George W. Sutton, with Carroll John Daly’s “Three Gun Terry” (which I wrote about here…) and “Kings of the Open Palm,” and Dashiell Hammett’s “Arson Plus,” appearing in 1923. In 1924, Sutton resigned and circulation editor Phil Cody replaced him.

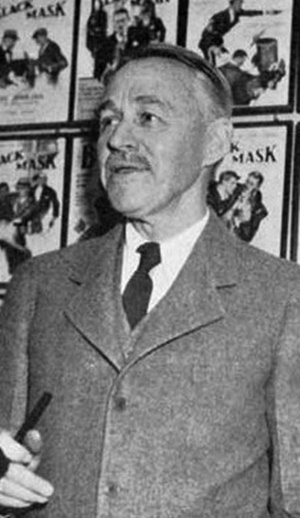

Cody pushed for more stories featuring Race Williams and the Continental Op, encouraged Erle Stanley Gardner to develop Ed Jenkins (‘The Phantom Crook’), and added Frederick Nebel and Raoul Whitfield to the magazine. Cody was pushed out by publisher Eltinge Warner in 1926, with Cody’s approval (he later became President of the company). Joseph Shaw, a former bayonet instructor in the army and an unsuccessful writer with zero editorial experience, took the reins (I mean, sure, why not?).

But it is Shaw who is revered as the editor who shaped and was largely responsible for the success of the hardboiled school. While he did not start the movement, it’s still a reasonable assertion. Shaw honed Black Mask into a razor sharp hardboiled pulp that dominated the field.

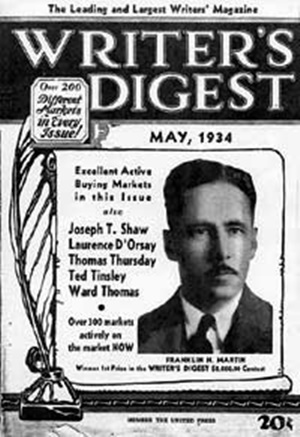

In May of 1934, Writer’s Digest featured a cover story titled, Do You Want to Become a Writer or Do You Want to Make Money? by Shaw. I’ve included that essay below, with a few comments of my own included in italics.

Two decades ago, Robert Thomas Hardy and Arthur Sullivant Hoffman were famed and loved by writers for their energy and patience in training and discovering new writers. Today, both these men are agents.

Robert Thomas Hardy was Erle Stanley Gardner’s trusted agent. When hardy passed away, his wife Linda took over the business. She and Gardner butted heads until he fired her. She badmouthed him in the industry, hurting his sales.

Their successor in the hearts of hundreds of writers is Joseph T. Shaw, editor of Black Mask, and prince among editors. At 578 Madison Ave., New York, Joe Shaw, about whom an enemy once said, “If he likes you, he’ll do so much for you, it’s pathetic,” is building up and developing scores of new writers.

Shortly we hope to have Mr. Shaw send us one of Black Mask’s published stories with running fire critical comment on the story by Mr. Shaw.

Writer’s Digest (May 1934)

Do you want to become a writer or do you want to make money?

You think the two are synonymous? Not with the frequency you might suppose.

If you want to make literature and a name for yourself as a really fine writer, you must face the fact that your market will be confined to a few quality magazines that pay low rates and to book publishers. If you believe you have it in you to be another O’Neill, Lewis, Hergesheimer, and are willing to endure the necessary years of struggle and apprenticeship, go to it; you’ll succeed eventually and make enough money to live a very full and happy life.

If, however, you want to write not for the sake of making literature, but of making a living, making money, in what seems to you to be an agreeable way of doing so, and if you want to accomplish this with the least possible delay, then forget literary ideals and concentrate all your efforts on creating what the great mass of the reading public want and are willing to pay for.

There are two main divisions in this field—the white paper magazines and the rough paper magazines. It is in regard to the latter that we are concerned in this article.

Here, Shaw is making a distinction between writing for the pulps and for the higher paying, higher quality, paper ‘slicks.’ His essay is about the pulps, of which Black Mask was arguably the best.

Rough paper magazines—wood-pulps, to use their facetious moniker—are very numerous, roughly they number more than a hundred, and their reader following goes well into the millions.

Rough paper magazines—wood-pulps, to use their facetious moniker—are very numerous, roughly they number more than a hundred, and their reader following goes well into the millions.

From the few hundred thousand of the first years of rough paper magazine appearance, this market has broadened satisfactorily and has now attained proportions that are very worthwhile to reckon with. When you consider that in numbers, approximately one out of every twenty men, women and children in the United States each month read a wood-pulp, you have an idea of what a source of entertainment and enjoyment to the people of the country this type of periodical has become.

It is too big a market to be taken lightly from any angle, too filled with possibilities to be looked upon disparagingly. Indeed, it is worthy and deserving of the most thoughtful consideration and serious effort not only to retain its present scope but also to increase its magnitude in possible and logical directions.

Granted a measure of natural gift and normal erudition, it should not be difficult to enter this broad field as a writer. To maintain it in an assured position of monetary success requires a measure of study, adaptability and whatever work may be necessary to attain facility and skill.

At the outset it might be helpful to the new writer to have a broad understanding of the field he is about to exploit.

In the first place, due to economic reasons, rough paper fiction attempts less to guide than it does to gauge and meet public taste.

Unlike the several contributing factors in the smooth paper magazines—format, illustrations, advertising, style, fad and what not—rough paper magazines are dependent for their circulation upon the popularity of their fiction alone. It must be popular, it must be what the majority of certain classes of the people want or they go out of business.

Under the circumstances you should not look for altruistic motives on the part of the editors and publishers of the pulps. No doubt many of them would like to see this distinctively virile field as a whole on a higher plane than its greatest volume typifies; but adventuring along such lines, commendable as it might be from certain points of view, is not warranted as a commercial experiment.

I’ve long felt that Shaw held his nose and put Carroll John Daly’s stories featuring Race Williams on the cover, knowing that sales were significantly greater when he did so.

Popular taste—honest, in that it reads what it likes regardless of fads and the preferences and opinions of others—popular demand molds the character of rough paper fiction more than does editorial and writer inspiration. The editors act for the most part in an interpretive capacity; the writers deliver merchandise specified.

Popular taste—honest, in that it reads what it likes regardless of fads and the preferences and opinions of others—popular demand molds the character of rough paper fiction more than does editorial and writer inspiration. The editors act for the most part in an interpretive capacity; the writers deliver merchandise specified.

Get clear in your mind, then, at the outset that to be successful in the rough paper field you must write to popular taste.

In this connection I am reminded of one very successful writer in this field who has spent years patiently studying and analyzing public mental capacity and taste of various markets and framed his stories for the respective magazines accordingly. The interesting points about this are that he has made money and is versatile. He has hit his markets with rare shrewdness. He is accounted among the most popular writers in widely divergent fields, for his stories in one magazine, for example, are not read or liked by the audience of another.

The ability to gauge this taste accurately is the key to the success of the best paid writers in the field today, and if they are at all versatile they can employ this ability to advantage in as many markets as they are capable of supplying.

The earlier newsprint magazines covered a wide range of subjects. Shortly there followed the idea of specialization, that is, a larger number of magazines each devoting its contents to a specific subject or section of the field-adventure, romance, sex, war, aviation, westerns, crime, detective, mystery, the pseudo-scientific, fantasy, and the like.

For an excellent look at the history of the various pulp genres, I HIGHLY recommend Ed Hulse’s The Blood ‘N’ Thunder Guide To Pulp Fiction.

The writer has a wide range here from which to choose and will no doubt make his first try in the particular subject in which he feels himself most familiar and to which he can give his most natural expression.

Generally speaking, the dominant demand in all sections of the field is in the matter of producing reader reaction or effects.

That these effects are exaggerated, often beyond the bounds of sane reason, must be put up to the tastes of this special reading public, many of whom seem not to quarrel with even absurdities so long as the particular story holds something of interest to them.

And now let us seek the elements which developed, will produce the most effective writing skill in this rough paper field, and particularly in its detective fiction.

Accepted a certain fluency and an adeptness in the choice of words to express the mental image simply, clearly and understandably, style has little to do with it and mannerisms far less if anything at all. Type and character of stories to be emphasized, likes and dislikes, the use or disuse of the familiar properties of the crime and detective story vary with the several magazines and can no doubt be ascertained by a study of the respective magazines or by inquiry of the editorial offices.

So far as Black Mask is concerned there is little we enjoy more in our editorial work than a chat with a serious writer of promise who wants to go somewhere.

With regard to our general requirements, we might say that Dashiell Hammett did his work very well. We are of course seeking another Hammett, but we distinctly do not want his imitation. And we expect it should be some time before we see another with his inflexible purpose and indomitable will that disregarded ill health, a measure of poverty, even the absence of an early scholarly environment and yet achieved their aim.

I like this. “Look, kid, you’re not Hammett. Don’t try to be.”

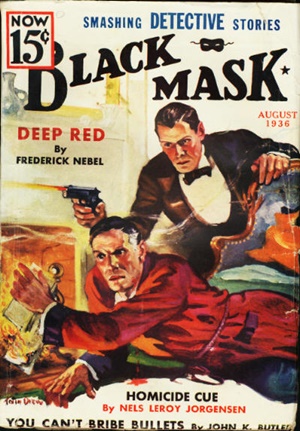

We are satisfied that Frederick Nebel, Raoul Whitfield, Erle Stanley Gardner, Carroll John Daly, George Harmon Coxe, Eugene Cunningham, W.T. Ballard, Theodore Tinsley, Roger Torrey, are all doing their work exceedingly well, and we do not need material along their respectively different lines. We do want stories unlike those of any one of them in type, character and treatment.

I’d like to point out that A (Black) Gat in the Hand managed to write at least a bit about every one of those authors above, except for Eugene Cunningham, over the course of this column!

But, as suggested, the requirements of the different magazines are superficial in many respects so far as the fundamental principles of writing skill are concerned, since the respective requirements can be expressed at will when writing skill is attained.

And among these cardinal principles simplicity and clarity must rank high. Your object is to accomplish an emotional effect upon your reader. You have a chance to do this if he can follow your story clearly and understands what it is all about. You have little or no chance, outside the sensation of shock, if your story confuses him, if it is too complicated in expression, structure or plot, or too subtle, so that he is at a loss himself to know exactly where his sympathy should lie or why it should be aroused at all.

Buyers in the majority of rough paper magazines want to take their stories in their stride, to read them while they run or ride. They do not want to stop in the middle of a story and go back to untangle confused threads or re-identify characters. It is for this reason that similarity of characters, particularly with respect to names of similar appearance, should be avoided.

I hate it when I can’t keep characters straight because their names are a bit too similar. Or start with the same letters. Especially if they aren’t one of the two or three main characters – the ones that have been impressed in my mind. If I have to stop and try and recall who is what, the story is losing me.

Swift movement and speed of action are other essentials in this age of fast tempo, but speed of action should not be confused with many rapid, meaningless notions.

Swift movement and speed of action are other essentials in this age of fast tempo, but speed of action should not be confused with many rapid, meaningless notions.

Long descriptive openings are for the most part taboo. For that matter these too often tedious stretches have little place in any part of a rough paper story of today.

Start your story in action if you can do so quickly. Identify your characters so that the action will be understandable to the reader; and keep it moving all the way to the end. To accomplish this, it is not necessary to stage a gun battle from start to finish, with a murder or a killing in every other paragraph. You can keep it alive and moving, when sympathy is once aroused, by tension and suspense, through dialogue or other form of plot development, when action is absent. Action in one form or another is, however, pretty generally in demand.

This!

Logic and plausibility are much abused terms. As a matter of fact, although they are at times mentioned editorially, in by far the greatest volume of crime and detective fiction they are completely disregarded, while rapidity of motion, exaggerated menace and exaggerated action are substituted in their stead, and, let it be said, with the apparent approval of many readers of the crime magazines today.

While it must be admitted that their use can produce the strongest possible emotional effects-since the happenings carry the illusion of reality-the danger lies in the fact that unless skillfully employed, their demands tend to clog the smooth, swift run of the story.

After all, their acceptability depends upon the treatment, upon the manner in which the material is presented to the reader. If it is done in such a way as to seem logical, the writer has little further worry in that regard and he may speed up his action as much as he sees fit. Where plausibility enters the question, the writer merely has to have his characters move and talk, act and react as real human beings would do in like situation, however imaginary, and his task in that respect is done.

Make your characters and their actions seem plausible, even if the setting isn’t. Huh…

In addition to these elements there is one general principle that is quite fundamental. Unless you have a clear mental picture yourself, you can scarcely expect your reader to get a clear, understandable impression of your thought. If your own ideas are undeveloped or confused, your purpose in your story unclear in your mind, its presentation will not be less so. Thus it would seem that word choice and arrangement, diction if you will, come secondary to clear thinking. If your mental image is clear, you will have no difficulty in expressing it in the simple language and simple technique of rough paper fiction.

In addition to these elements there is one general principle that is quite fundamental. Unless you have a clear mental picture yourself, you can scarcely expect your reader to get a clear, understandable impression of your thought. If your own ideas are undeveloped or confused, your purpose in your story unclear in your mind, its presentation will not be less so. Thus it would seem that word choice and arrangement, diction if you will, come secondary to clear thinking. If your mental image is clear, you will have no difficulty in expressing it in the simple language and simple technique of rough paper fiction.

I kinda feel like this is a swipe through time at pantsers…

I often wonder if this preliminary fumbling at the typewriter, of which writers so frequently speak, is not due less to meager facilities of expression than to a confused idea of what it is desired to express.

It is hardly to be expected that you will have a clear image of your whole picture before you begin to express a part of it; and often it requires a partial expression of the whole before you observe that it is not complete.

Of course, where speed of production is so important to the moneymaker in this field, such reworking is apt to be costly, but is nevertheless practiced by many successful rough paper writers whose hold upon the audiences they have built up seems to warrant a greater care in workmanship than is typical of the great majority of this fiction of the moment.

Thus, if a writer enters this field with the sole purpose of making money in it, particularly if he wishes to cash in on the wild surges that endeavor to capitalize the utmost of popular fancy, he should start with no illusions of literary ambition. If he will train himself in clear thinking he will have an asset that will contribute greatly to speed of production. If he will attain a writing skill combining the various elements suggested, and is possessed of ordinary creative imagination he should have all that will be required.

Authored by Joseph T. Shaw; from Writers’s Digest (May 1934).

Keep in mind, this was written eighty-four years ago, for a now long-gone market. But it’s an interesting look into the pulp market at the peak of its popularity. And have no doubt, there is still some solid advice in here. I thought it was a pretty interesting piece.

Previous entries in the series:

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

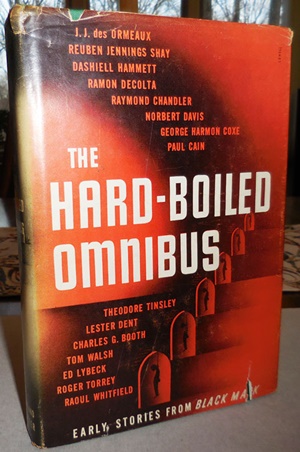

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #3

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #4

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #5

A (Black) Gat in the Hand will run through Tuesday, January 1st. A new Robert E. Howard-centric column will take its spot on January 8th. Hey – we are a World Fantasy Award-winning website, you know!

Bob Byrne’s A (Black) Gat in the Hand appears weekly every Monday morning at Bla ck Gate.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March 2014 through March 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!). He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he will be in the upcoming anthology of new Solar Pons stories!

[…] (Black Gate): The hardboiled school was born in the page of Black Mask Magazine under the editorship of […]