A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Maynard’s ‘Shades of Yellow’

Because I find it’s easier to get somebody else to do all the heavy lifting, I secured another guest poster for this week! Fellow Black Gater William Patrick Maynard knows more about Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril genre than anybody else I know. And if you see his credentials at the end of the post, you’ll understand why! Today, he takes a pulpy look at the ‘menace from the Far East’ topic. Read on!

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” — Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

Context is a challenge in politically correct times that seek to view the past through the myopic lenses of an eternal present. Over 130 years ago, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created an archetype in fiction with his consulting detective Sherlock Holmes. While Holmes lives on at least in name and reputation, most of his antecedents, contemporaries, and successors in the fantastic fiction of the Victorian and Edwardian eras are rapidly fading into obscurity.

Context is a challenge in politically correct times that seek to view the past through the myopic lenses of an eternal present. Over 130 years ago, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created an archetype in fiction with his consulting detective Sherlock Holmes. While Holmes lives on at least in name and reputation, most of his antecedents, contemporaries, and successors in the fantastic fiction of the Victorian and Edwardian eras are rapidly fading into obscurity.

While forgotten by the public at large, the traits and exploits of many of these same characters have been disseminated into today’s pop culture icons (James Bond, Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and the glut of superheroes that continue to dominate movie screens). What remains of the past is largely through the efforts of pulp specialty publishers and public domain reprint specialists who keep these classic works in print for a niche market that still reads works from a different, simpler, though not always better, world.

Much of this fantastic fiction sprung directly from colonial viewpoints of the British Empire. Among the xenophobic byproducts of colonialism in popular culture was the Yellow Peril, the paranoid delusion that Chinese immigrants were plotting to conquer the West. There was certainly crime in Chinatown: there is always crime among the economically underprivileged, but what made the Yellow Peril thrive as a sub-genre of the thriller was the creation of a brilliant, amoral Chinese criminal mastermind in the same fashion as Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty and Guy Boothby’s Dr. Nikola.

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu became the personification of the Yellow Peril. Without the character’s introduction, the sub-genre would never have prevailed. Fu Manchu took the reading public by storm just before the outbreak of the First World War and remained a bestselling franchise up to the Cold War. Rohmer’s insidious fiend was everywhere: magazines (slicks, not pulps), books, newspaper strips, comic books, radio series, films, the theater, and eventually television.

Holmes and Fu Manchu were certainly among the most influential characters in the first half of the last century. Arthur B. Reeve’s American variation on Holmes, the scientific detective Craig Kennedy was likewise pitted against a variation on Fu Manchu, the diabolical Wu Fang in The Exploits of Elaine (1914), The Romance of Elaine (1915), and The Triumph of Elaine (1915). The Elaine triptych were inspired by the phenomenal success of the 1914 serial, The Perils of Pauline.

The silent era’s perennial damsel-in-distress Pearl White (Pauline herself) took the role when Reeves brought his trio of Elaine thrillers to the screen (the books were specifically created as movie tie-ins to bring the American Sherlock Holmes to a wider audience). Significantly, Reeve’s Wu Fang appeared in silent films nearly a decade before Fu Manchu made the transition.

The next Yellow Peril to have a major impact was Achmed Abdullah’s serial, The God of the Invincibly Strong Arms (1915-16). As one would expect from the author of The Thief of Bagdad (1924) and The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935), it is very well-written. Unfortunately, the serial is severely hampered by exceptional (even for its era) racism. Despite the author’s pseudonym (he variously claimed to be a sheikh as well as a cousin of the Russian royal family), he broadly painted all non-Europeans as negative stereotypes by repeatedly stating characters cannot be trusted if they are not white.

The unprepossessing narrator’s trusted Portuguese valet is continually reminded he is really a white man, though the narrator makes it clear he only says this to manipulate him and does not consider him white as he is a half-caste. The criminal masterminds here are a Moslem and a blue-eyed Chinese mandarin (who, within the story, is the inspiration for Rohmer’s Fu Manchu). The pair manipulate a bloodthirsty Hindu death cult to achieve their political goals of ending European colonialism.

The conflict brought about by colonialism and the author’s knowledge of what was then broadly termed the Orient is always interesting and the prose is uniformly strong throughout. The jingoism, which is extreme even for its era, will likely challenge many modern readers. Only the first two-thirds of the serial were printed in book form (The Red Stain in 1915 and The Blue-Eyed Manchu in 1916). Altus Press is planning to reprint the entire serial so readers may judge the serial on its own merits in its entirety.

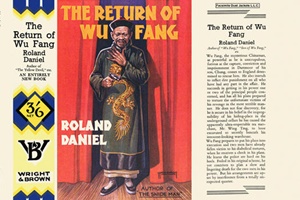

Interestingly, it was Wu Fang (as a name, if not a continuing character) who became ubiquitous with Yellow Peril villainy. Roland Daniel penned a very well-written series of Wu Fang thriller novels in the U.K. These are nothing like Fu Manchu or Arthur B. Reeve’s Wu Fang, as they are much more realistic crime stories set among London’s Chinese community. There were at least seven novels in the series published between 1928 and 1937. Two of them are back in print courtesy of Ramble House: Ruby of a Thousand Dreams (1933) and The Return of Wu Fang (1937).

Interestingly, it was Wu Fang (as a name, if not a continuing character) who became ubiquitous with Yellow Peril villainy. Roland Daniel penned a very well-written series of Wu Fang thriller novels in the U.K. These are nothing like Fu Manchu or Arthur B. Reeve’s Wu Fang, as they are much more realistic crime stories set among London’s Chinese community. There were at least seven novels in the series published between 1928 and 1937. Two of them are back in print courtesy of Ramble House: Ruby of a Thousand Dreams (1933) and The Return of Wu Fang (1937).

Daniel’s character is much more of a traditional Chinatown gangster, albeit one who has ambitions to cash-in and retire young. Daniel’s prose is smooth and his plots and dialogue are very reminiscent of British B-movies of the 1930s. The books are fast-paced fun with a surprising emphasis on female characters. Daniel’s female British spy is not a femme fatale or a damsel-in-distress, but a well-written independent woman. Of course, considering the era, she falls in love with the well-meaning Scotland Yard detective who is nowhere close to her equal, but that’s part of the charm of the stories.

Daniel deserves more attention. A very good writer who was anything but a Sax Rohmer imitator. His strong point is believable characters who manage to be something more than thriller stereotypes. Considering he was writing Yellow Peril thrillers, that is quite an accomplishment.

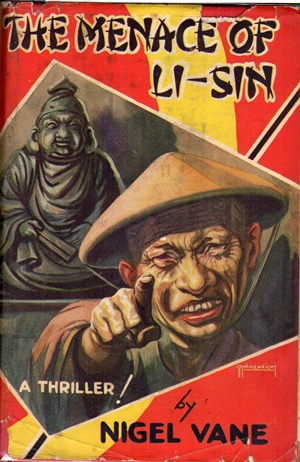

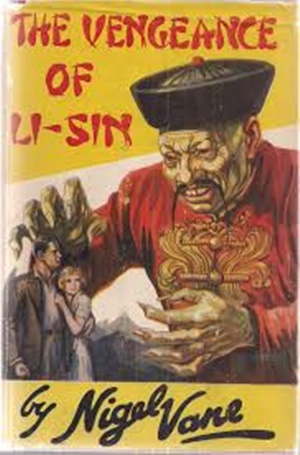

The Evil of Li-Sin (also available from Ramble House) collects a pair of entertaining Yellow Peril thrillers, The Menace of Li-Sin (1934) and The Vengeance of Li-Sin (1936). These are the only two of at least four novels in Gerald Verner’s Li-Sin thriller series that are still in print. Verner’s books are diverting hokum, but nothing more and marred by poor research on Asian cultures (for example, Buddha is repeatedly referred to as an Asian god). Verner’s dialogue sometimes seems risible at worst or charmingly quaint at best. To his credit, these are also not Fu Manchu imitations, but rather offer something a bit more grounded as Chinatown crime thrillers.

That said, the author was clearly familiar with Rohmer and late in his career, Verner penned a blatant Rohmer imitation, The Dragon Princess (1967) (which is back in print courtesy of Borgo Press) that features Yu-Malu, Verner’s imitation of Rohmer’s Sumuru, a female variation on Fu Manchu who appeared in five Rohmer novels of the 1950s (as well as an earlier radio serial, a pair of cult B-movies in the 1960s, and a bizarre sci-fi reboot in the 21st Century). Yu-Malu, like Sumuru, stands as entertaining late-period artifact of a bygone era.

That said, the author was clearly familiar with Rohmer and late in his career, Verner penned a blatant Rohmer imitation, The Dragon Princess (1967) (which is back in print courtesy of Borgo Press) that features Yu-Malu, Verner’s imitation of Rohmer’s Sumuru, a female variation on Fu Manchu who appeared in five Rohmer novels of the 1950s (as well as an earlier radio serial, a pair of cult B-movies in the 1960s, and a bizarre sci-fi reboot in the 21st Century). Yu-Malu, like Sumuru, stands as entertaining late-period artifact of a bygone era.

The Sign of the Scorpion (1935) offered a Hindu take on Fu Manchu amid well-worn Oriental trappings. This is the only book in Edmund Snell’s Chanda-Lung series still in print (again, courtesy of Ramble House), it offers readers a twist on the Yellow Peril formula by presenting a Hindu magician and criminal mastermind, Chanda-Lung and placing him in a series of vignettes drawn heavily from Sax Rohmer’s early Fu Manchu stories. Snell did better work elsewhere.

While some of his twists on Rohmer’s material are clever, the fact that he so blatantly copies the original is off-putting. The book is a fix-up (like the early Fu Manchu books as well) combining episodes from various Chanda-Lung short stories (though not in their order of publication) to knit a loosely-connected narrative. Snell’s prose intermixes wonderfully atmospheric scenes with hurriedly and poorly detailed action scenes. A frustrating book because the author clearly had the creativity and talent to deliver something much stronger.

The “Spicies” were considered pornographic pulps in their day, though the sex was mostly implied rather than explicit. Four Wo-Fan Yellow Peril stories credited to Bedford Rohmer appeared in New Mystery Adventures in 1935 and 1936. These were the work of the prolific H. Bedford-Jones and have not yet been collected in book form, but have been reprinted as facsimile editions of the original pulp magazines by Adventure House or in their ongoing reprint publication, High Adventure. The Wo-Fan stories are poorly written from a writer who was not above hack-work. You know you’re in trouble when the author’s pseudonym is the most entertaining part of a story.

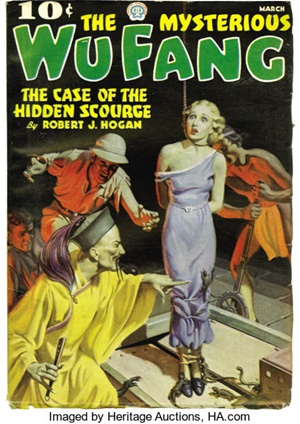

Popular Publications gave readers the finest Fu Manchu imitations this side of Robert E. Howard’s “Skull-Face” (1929) and “Lord of the Dead” (1934) which have been covered in detail elsewhere and are essential reading. Robert J. Hogan’s pulp title, The Mysterious Wu Fang and its successor, Donald Keyhoe’s Dr. Yen-Sin are the standout Yellow Peril titles. This ultimate version of Wu Fang (the Dick Tracy-inspired comic character, Dan Dunn also had a Wu Fang to contend with during the Depression) was pitted against G-man Val Kildare, an American variation on Fu Manchu’s nemesis, Sir Denis Nayland Smith of British Intelligence. Kildare, like Smith before him, was complemented by his own Watson, news correspondent Jerry Hazard.

Closely following the established Fu Manchu formula, Wu Fang’s unwilling femme fatale Mohra fell in love with Hazard and would repeatedly betray her master to spare the lives of Kildare and Hazard. Mindful of the audience demographics for pulp magazines, The Mysterious Wu Fang featured the reader identification character of Cappy, a spunky newsboy and boy scout who improbably accompanied Kildare and Hazard on their globe-spanning adventures. Hogan was also the author of Popular Publications’ successful G-8 and His Battle Aces pulp title which featured its own recurring Yellow Peril villain in the form of Dr. Chu-Lung.

Popular Publications employed Rohmer’s artist, John Richard Flanagan, to provide his lurid Yellow Peril artwork for covers each month. While there were many Fu Manchu imitations in the 1930s, The Mysterious Wu Fang looked and read almost like the genuine article and was providing readers with a new short novel each month. Popular Publications received a cease and desist letter from Rohmer’s attorneys. The Mysterious Wu Fang was promptly cancelled after its seventh issue while Popular Publications reworked the concept with a similar character.

The replacement title was Dr. Yen-Sin. While there was no mistaking Donald Keyhoe’s Yen-Sin was another variation on Fu Manchu, his nemesis was not another clone of Nayland Smith or Val Kildare, but a unique pulp hero who deserved greater recognition. Yen Sin faced Michael Traile, a G-man dependent upon yoga due to a freakish medical condition that prevents him from ever sleeping. Traile was ably supported by yet another newspaper correspondent, Eric Gordon.

Dr. Yen Sin belonged to the international criminal organization, the Invisible Empire, where he was known by the code name, the Cobra. Keyhoe detailed the character’s backstory involving the abduction of the Russian Grand Duke Damitri and Michael Traile’s first encounter with Yen Sin in China after the Great War.

Unfortunately, these points were drawn directly from Sax Rohmer’s 1919 Yellow Peril thriller, The Golden Scorpion which was part of the Fu Manchu continuity and featured Fo-Hi, known within the international criminal organization, the Sublime Order, by the code name, the Scorpion. Fo-Hi likewise was first glimpsed by the hero in China several years before the novel takes place and was likewise involved with the removal of a Russian Grand Duke just before the First World War.

Unfortunately, these points were drawn directly from Sax Rohmer’s 1919 Yellow Peril thriller, The Golden Scorpion which was part of the Fu Manchu continuity and featured Fo-Hi, known within the international criminal organization, the Sublime Order, by the code name, the Scorpion. Fo-Hi likewise was first glimpsed by the hero in China several years before the novel takes place and was likewise involved with the removal of a Russian Grand Duke just before the First World War.

Dr. Yen Sin made the same mistake that brought The Mysterious Wu Fang to a premature end by steering too closely to Rohmer. The third bi-monthly issue of Dr. Yen Sin had just gone to press when Popular Publications cancelled the series following a further cease and desist letter initiated by Rohmer’s attorneys. Perhaps without John Richard Flanagan’s artwork, so synonymous with Rohmer’s work, they might not have attracted so much unwanted attention.

More likely it was a combination of factors, the most important of which was a monthly (or bi-monthly) pulp title imitating (and sometimes outdoing) Rohmer was perceived as a threat to Fu Manchu’s marketability (particularly each new Rohmer novel’s being vied for by the slicks for serial rights) if it were seen so commonplace that the pulps had their own Fu Manchu using Rohmer’s favored Fu Manchu cover artist.

For just over a year, Popular Publications gave readers the next best thing to Rohmer’s Devil Doctor. The Mysterious Wu Fang and Dr. Yen-Sin are familiar, but stand on their own as classic pulp thrillers in the Yellow Peril sub-genre. Keyhoe, like Robert J. Hogan before him, is among the best of the Yellow Peril authors to follow in Fu Manchu’s wake.

There is no denying the inherent racism of Yellow Peril fiction. Much like minstrel shows, the racism is its reason for existing. At its best, yellow peril fiction offered readers exotic thrills and excitement that dared them to imagine adopting the values and mores of a different culture, one that withstood Western imperialism and tempted us with greater knowledge and power as well as the lusty allure of something far more dangerous and pleasurable than we could ever find back home.

Previous entries in the series:

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard is the licensed continuation author of the Fu Manchu series for the Sax Rohmer Estate. His third book, the long-anticipated Triumph of Fu Manchu, is due for 2019 publication by Black Coat Press.

Bob Byrne’s A (Black) Gat in the Hand appears weekly every Monday morning at Black Gate (until they finally get around to changing the password!).

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March 2014 through March 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!). He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.