The Fantastic Novels of Harlan Ellison

Harlan Ellison speaking to the audience at the Los Angeles

Science Fantasy Society, May 1982. Photo by Pip R. Lagenta

Harlan Ellison published three novels early in his career, and spent the rest of his life trying to complete another1. Despite a large and successful body of work, and the willingness of publishers to pay large advances for a novel, he never succeeded.

Returning to the novel form was important for Ellison; he announced the titles of works in progress as “forthcoming” in the front matter of his short story collections, ghost titles that would appear in successive volumes, sometimes for years, then vanish to be replaced by new ones. In 2010, when he was 76 and announced he was dying, Ellison said that he was working on a new novel, The Man Who Looked for Sweetness;2 and in 2014, shortly before he suffered the stroke that ended his writing, he returned to an earlier project.3 Completing another novel was a dream he never relinquished.

All writers leave behind abandoned or unfinished projects, and those incautious enough to include forthcoming volumes in lists of their published works will sooner or later include a title that never appears.4 If Harlan Ellison differed from his peers in this respect, it is in how early and how often he did this. As early as 1962, in his collection Ellison Wonderland, his list of published titles included a “forthcoming” one: Don’t Speak of Rope, a crime novel to have been written in collaboration with Avram Davidson. (He later described the project as ill-conceived.) A 1967 collection cited two more “forthcoming” novels, Demon with a Glass Hand (an adaptation of a teleplay Ellison had written in 1964 for The Outer Limits, which in turn was based on an abandoned novel entitled Obituary for an Instant5), and Dial 9 to Get Out (a novel about contemporary Hollywood that Ellison called “more than slightly autobiographical”6). A year later — in the late sixties and early seventies Ellison was publishing a short story collection every year — he added The Sound of a Scythe, described as “a revised, expanded version” of his SF novel The Man with Nine Lives.7 These three titles continued to be listed in his books for several years.

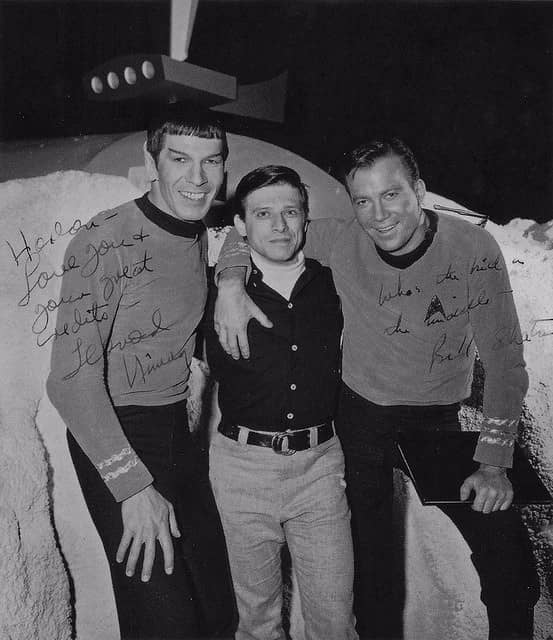

Harlan Ellison with Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner during

filming of Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever”

In 1972, at the Los Angeles World Science Fiction Convention, Ellison told a large audience that his 1970 novella “The Region Between” would form the middle third of a novel, The Prince of Sleep. Ellison made the story sound exciting (the published novella ends with the destruction of the universe), which somewhat made up for his other announcement: that he had broken with Doubleday and The Last Dangerous Visions would soon be with another publisher. Not long after this, Locus announced the sale of the novel to Ballantine8. The novel, which was never completed, would in time be sold to at least two subsequent publishers.

It was two years after the Locus item, however, when Pyramid began to issue a uniform edition of old and new Ellison titles, that the “forthcoming novels” truly began to flourish. The list of Ellison titles in the front matter of The Other Glass Teat (published June 1975) included two more “forthcoming” novels, The Dark Forces #1: The Salamander Enchantment, based on a never-produced TV script Ellison had written a few years earlier10 and something called RIF. (Oddly, it would be a few years before Ellison listed The Prince of Sleep.) The Dark Forces #1 was identified as forthcoming in 1975 — that is, within the next six months — while RIF, which Ellison later said was based on the life of Robert E. Howard,11 was given as a 1976 title.

When Ellison published Deathbird Stories later that year, no fewer than twelve “Forthcoming” titles were listed: collections, novels, a textbook, and The Last Dangerous Visions. It was a delirious apotheosis, and the next year12 Ellison added a third forthcoming novel, A Boy and His Dog, which would become, after The Last Dangerous Visions, his most notorious unfinished project.

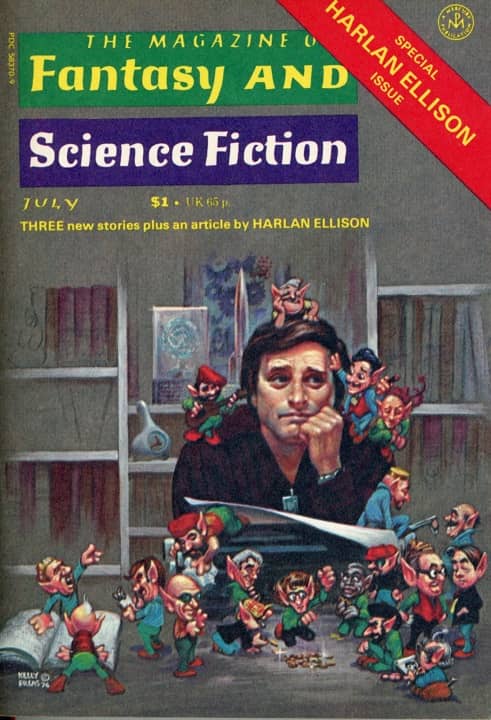

The special Harlan Ellison issue of The Magazine of

Fantasy & Science Fiction, July 1977. Cover by Frank Kelly Freas

Ellison’s 1969 novella had won a Nebula Award and was made into a film in 1975. That spring, while visiting Yale, Ellison told me that there would soon be a Special Harlan Ellison issue of F&SF, which would include a 25,000 word novella, a sequel to “A Boy and His Dog,” to be called “Blood’s a Rover.” Evidently the story, which Ellison regarded as a personal favorite, continued to tug at him.

(Later he claimed that the story had been conceived as a novel all along, and that he had only acceded to publication of the novella because Michael Moorcock asked for a contribution to New Worlds and that section could stand alone.13 His insistence on this point, despite ample evidence that it could not be true, was evidently connected with his frequent insistence that he had never written a sequel and never would.14)

When he announced in 1976 that the project would be a novel, it was listed as due for publication that year, the same dates now given for RIF and The Dark Forces. Did Ellison actually expect to complete and publish three novels that year (along with, we were assured, The Last Dangerous Visions)? Evidently he did. And a year later, in honor of the Special Harlan Ellison issue of F&SF, Dell Books congratulated Ellison and announced the that it would be publishing “The Prince of Sleep, his first novel in over fifteen years, a major work of fantasy for 1978.”14

Despite this severe overcommitment, Ellison continued to propose and sell more novels. On August 29, 1980, the New York Times ran a small item by Herbert Mitgang in its Books section.

Quite often these days publishers sign up authors for multibook contracts to provide security and insure they will stay put. For example, Harlan Ellison, a West Coast writer, has a three-book contract with Houghton Mifflin. ‘Shatterday,’ a collection of short stories, is due in November. It will be followed next year by a fantasy novel, ‘The Prince of Sleep,’ and later by ‘Shrikes,’ which Houghton’s editor in chief puts in the category of a ‘best-selling mainliner.’ And what are its best-selling ingredients? Well, the story concerns five women who determine, each for different and valid reasons, to kill their husbands. That sounds pretty mainline.15

Shatterday duly appeared, but neither novel ever saw light of day. Ellison had bragged to an interviewer that Houghton Mifflin had paid $154,000 for Shrikes “just on the basis of telling the plot to the editor.”16 Possibly that amount represents the full advance — the last portions of which would be paid only after delivery of the finished manuscript — but the Houghton editor’s words suggest that they indeed had big hopes for the novel.

Certainly Ellison did. Speaking to another interviewer in 1979, he said:

I’m a word-of-mouth, underground writer, really. I won’t be that two years from now, I promise you. There’s something in the offing. Two years from now, I will be on the top of the best-seller list, and everybody will know the name and everybody will buy the book. Every asshole who reads under a hairdryer or while sitting with a can of beer in his hand is going to be buying and reading the book that I will be writing, the novel that I’m writing and that will be top of the best-seller list. I promise you. Number one best-seller in the nation.17

It seems clear that Ellison is talking about Shrikes, although he wished to keep both the title and the “high concept” to himself. His confidence that he could complete the novel in time for it to be published two years later, is, once more, striking.

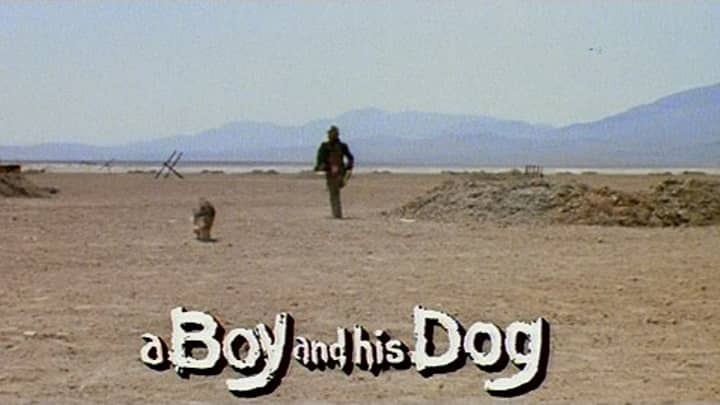

Don Johnson in A Boy and His Dog (1975)

The Dark Forces and RIF soon vanished from the lists, but A Boy and His Dog, now retitled Blood’s a Rover, had been purchased by Ace a few years earlier, for a reported $50,000. In a 1981 interview Ellison declared that “My novels Shrikes, Blood’s a Rover, Nights in the Gardens of Trepidation, and The Prince of Sleep will all be out in the near future.”18 (Nights in the Garden of Trepidation he described as “a light fantasy about a troll who inherits the Brooklyn Bridge” that he had also sold to Ace.)

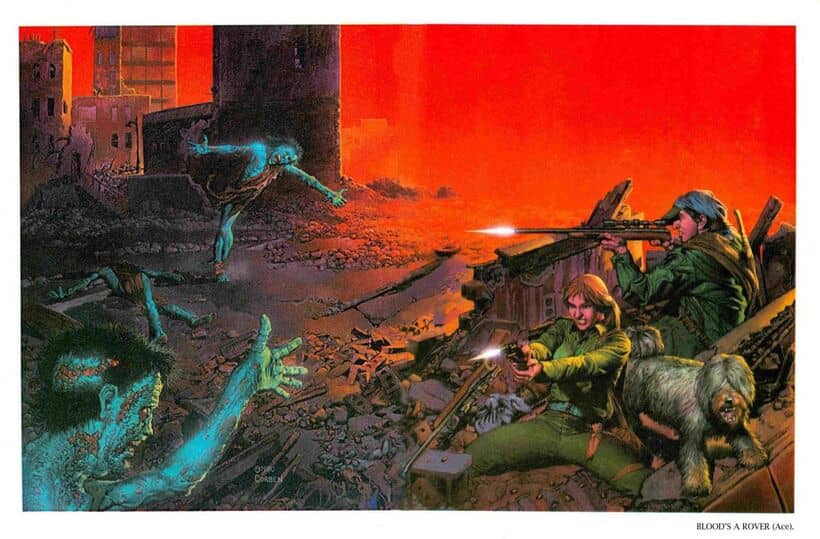

Keen to publish Blood’s A Rover as a trade paperback, Ace (which had taken over Ellison’s backlist from Pyramid and would soon be issuing a uniform edition of its own) printed up a number of wraparound cover flats — an unusual practice for a novel whose manuscript had not yet been delivered — that hailed the book as “Harlan Ellison’s First Novel in 19 years.”

Richard Corben’s cover art for the unpublished Ace edition of Blood’s a Rover.

From the Richard Corben Collector Cards set published by Comic Images (1993)

They scheduled the book for October 1980 and that summer took the unusual step of soliciting orders from bookstores, something one only does when publication is imminent. “Has Harlan delivered the book?” the proprietors of The Other Change of Hobbit bookstore pointedly asked the Ace salesman. “He’s delivering it on Monday,” the salesman assured them. They laughed at him.19

Ellison never delivered the manuscript, and later in 1981 Ace cancelled the contract and demanded a return of the advance. The galling details were reported in Locus20, which noted that the advance was absorbed into the accounting of the reprints Ace would go on to publish).

Poster for A Boy and His Dog (LQ/Jaf Productions, 1975)

Ellison announced no new novels for the rest of the eighties, or the nineties. (The appearance of “The Region Between” in his 1988 collection Angry Candy suggests a tacit acceptance that he would not complete The Prince of Sleep.) Of those already-announced titles, the only one he continued to mention was Blood’s a Rover. During the years that Ellison was trying to turn “A Boy and His Dog” into a novel, he published two short stories set in the same background: “Eggsucker” (1977) and “Run, Spot, Run” (1980). In 1989 Vic and Blood: The Chronicles of a Boy and His Dog, a “graphic adaptation by Richard Corben” of the three stories, was published under the two men’s names. In an afterward Ellison declares these stories “the first three sections” of Blood’s A Rover, which would run 100,000 words and which, “If the heavens don’t part and swamp us,” would be published in 1990.21

No further stories from the sequence appeared. When the graphic novel was republished in 2003, Ellison wrote an introduction in which he declared:

And I’ve written the rest of the book, BLOOD’S A ROVER. The final, longest section is in screenplay form – and they’re bidding here in Hollywood, once again, for the feature film and TV rights – and one of these days before I go through that final door, I’ll translate it into elegant prose, and the full novel will appear.22

I’ve written the rest of the book. Ellison spoke as though to adapt a teleplay into prose was such an easy task that one could treat it as already accomplished, although he had never turned Demon with a Glass Hand or The Dark Forces #1 into their promised novels, and he had handed off the task of novelizing his teleplay Phoenix Without Ashes to Edward Bryant. Writing a sustained piece of prose, something longer than the novellas he occasionally published, was something he could no longer do.

It was not until 2010 that Ellison again announced that he was working on a novel. That was the reference to The Man Who Looked for Sweetness, which he declared “three quarters”23 finished. Whether this project was based, like nearly all the others, on some already-written version (published story, script, television treatment) that he believed he could expand quickly, or whether it was conceived as an original work, is not known.

The following year, however, Ellison actually published one of these long-promised titles. The Sound of the Scythe appeared in an omnibus, The Sound of a Scythe and 3 Brilliant Novellas, which Ellison self-published under the imprint, Edgeworks Abbey, that he created to bring his works back into print. The original novel (first published in shorter form in Amazing Science Fiction Stories in 1959 then as part of an Ace Double a year later) seemed unpromising enough — Ellison was still an extremely crude writer at that point in his career, and outer space adventure was never a genre in which he excelled — that one wondered what a “revised and expanded” edition could salvage of it.

Although the book’s publicity material declared that it had been “expanded by 25% from its 1960 publication and extensively rewritten by Ellison for this appearance. Virtually every page has been finessed by the author,”24 it is difficult to see much evidence of rewriting. The opening line of the 1960 edition — “His relatively new face was clammy with sweat,” which is characteristic of Ellison’s early prose style — is unchanged in the 2011 text, and when I looked for the worst-written sentence I could find in the original edition (it was “Lederman’s voice cut through with softness as calm as a quicksand bog”), I found it was present, unchanged, in the new one.

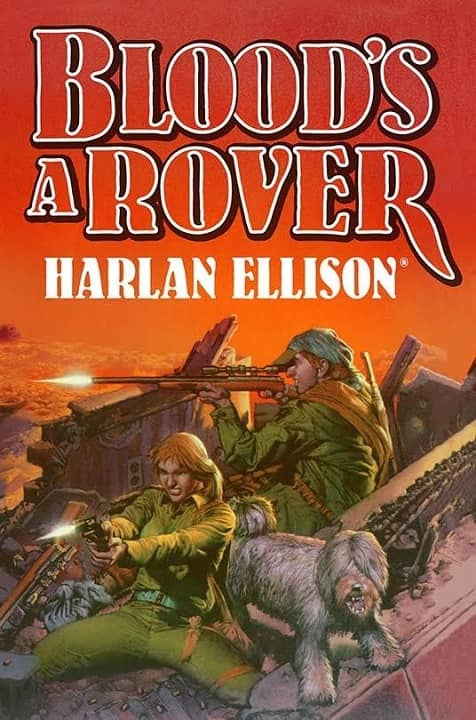

Blood’s A Rover (Subterranean Press, 2018). Cover by Richard Corben

One more “forthcoming” title eventually appeared, at least in some form. In 2018, long after anyone had given up on ever seeing the completed novel, Ellison published Blood’s A Rover, a limited-edition volume comprising the three stories, a few snippets, plus the teleplay that Ellison had written in 1977. The script is a sequel to the three stories, and it seems clear that Ellison’s plan in the late seventies to turn this into a novel involved converting the screenplay into prose. These disparate bits, running 232 pages, is as close to a finished novel as Ellison could get, and he clearly published it in its present form when he finally gave up on completing the project.

Why was writing a novel so important to Ellison, and why was he, after his mid-twenties, unable to complete one?

The first question is more easily answered: The novel, in the 1950s and 1960s (and it is important to remember that Ellison grew to adulthood in the Fifties) reigned supreme in American culture. D.H. Lawrence had called the novel “the one bright book of life,” while Gore Vidal called it the “Great Bitch” of modern literature. By the 1950s, when Vidal made this remark, a writer could no longer make the literary big time by producing short stories, or plays, or poems, as had been possible at various times over the previous half-century. Even in science fiction, to be a major writer was to be someone who wrote novels.

This was important to Ellison, who never wished to create art in obscurity. Whatever Ellison wrote in the sixties and later, he was thinking about novels. When his screenplay for the first episode of his television series The Starlost was novelized by Edward Bryant, Ellison claimed co-credit for the novel, which was not standard practice for novelizations. A few years earlier, in the closing pages of Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison remarked that his Introductions totaled 60,000 words of copy, and added, “That’s a novel.”25 And when Ellison published “Cutter’s World” in the third volume of Brain Movies, The Original Teleplays of Harlan Ellison (2013), it is identified on the cover as “an original novel as screenplay.” These are strange claims to make, and speak to how important writing a novel was to him.

For more than fifty years — from the early sixties to his death in 2018 — Harlan Ellison worked to complete another novel; to scant this element of his career is to misrepresent it. That’s one of the reasons that Nat Segaloff’s awful biography is so bad: save for the debacle of Blood’s a Rover, of which Segaloff gives a brief, embarrassed account, he seems to be unaware of these novels, though Ellison mentioned them over and over again.

As to why Ellison could not complete a novel, I can only venture a theory. Ellison’s volatile, mercurial temper; his difficulty in completing projects on time; his trouble with completing long projects at all; the intensity of his prose, which always shines brightest in his short stories and falters in his longer fiction — all of these suggest (I am not the first to suggest this) that Ellison suffered from an attention deficit disorder.

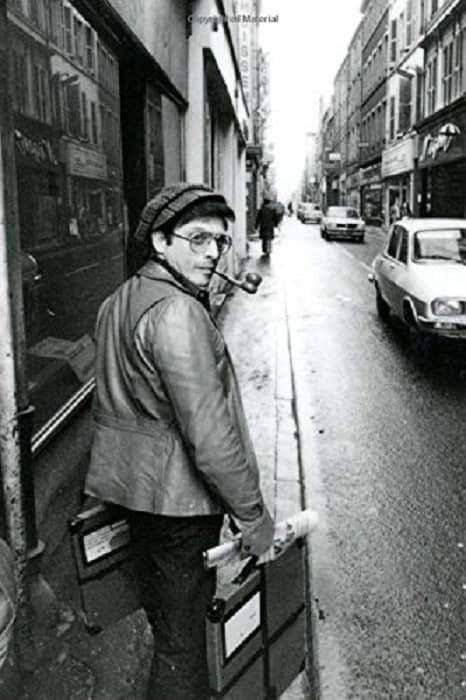

Ellison in the early 1970s

This is not an astonishing claim: lots of writers do. And historically, writers who need to maintain their focus long enough to complete their work have resorted to varieties of self-medication. Nicotine was always the big one, although writers in the fifties took recourse, to a surprising degree, in amphetamines. (Robert Heinlein used Dexedrine, and both W.H. Auden and the monstrously prolific L. Ron Hubbard swore by Benzedrine. Philip K. Dick famously relied on a variety of amphetamines to maintain his writing output.) Harlan Ellison did not take drugs, but he smoked heavily as a young man, using his four-pack-a-day habit to meet writing deadlines. (Barney Dannelke, a longtime friend, recalls being told that when the habitually neat Ellison needed to finish a story, he would deny himself the right to empty his overflowing ashtray until he had completed it.) Ellison quit smoking in 1962,26 and was never again able to complete a novel.

This was very likely the result of his abandonment of nicotine with its potent power to focus attention. Although Ellison soon moved to Hollywood, where he began a successful career working for television and movies, writing a 120-page (or shorter) script is a very different undertaking than completing a 200-page (or longer) work of prose, and Ellison’s ability to carry out the former did not mean he could still do the latter. Even the strategy of adapting a finished script into prose, a plan that Ellison confidently announced on various occasions, proved unfeasible.

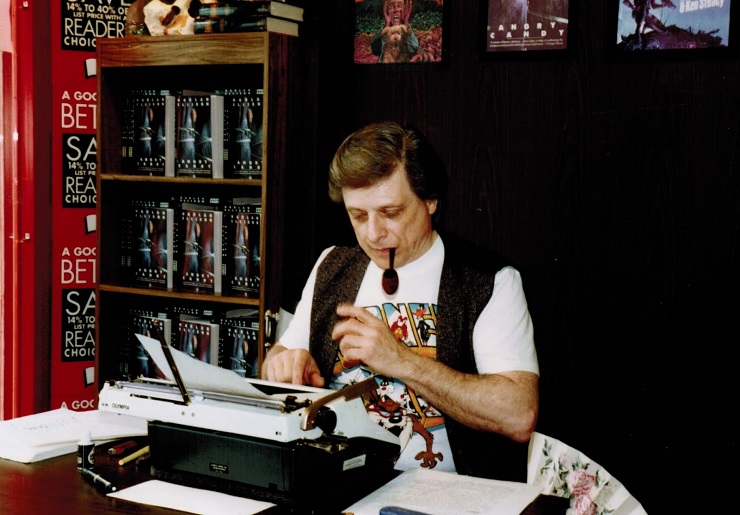

Harlan Ellison writing “Jane Doe #112” in public at Bookstar Bookstore,

New Orleans, March 1990. Photo by O’Neil De Noux

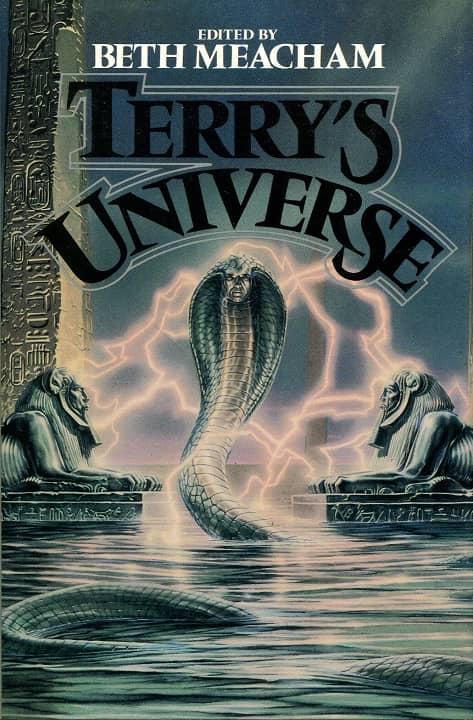

As it was, Ellison found himself resorting to various expedients in order to complete projects. He often arranged to work under self-imposed deadlines, writing in a bookshop window or finishing a short story just in time to give a scheduled reading at a convention.27 Even these constraints were not always enough to allow him to focus long enough to finish a story: he promised a contribution to the Terry Carr memorial anthology Terry’s Universe, but though he persuaded Tor Books to use the painting he hoped would inspire his story for the book’s cover28, he never managed to finish it.

Harlan Ellison decreed that all of his unfinished manuscripts be burned upon his death. If his literary executors carried this out, Ellison scholars (should his work become the subject of scholarship and study in the years to come) will never know how much of Nights in the Gardens of Trepidation or The Man Who Tasted Sweetness was written, or whether anything existed of the other works beyond the shorter, published texts or the dramatic versions.

Terry’s Universe, edited by Beth Meacham

(Tor Books, June 1986). Cover by Mike Presley

My guess is that little exists. Even Vladimir Nabokov (not someone given to hyperbolic claims about forthcoming work) described as “not quite finished” a late novel that, when the manuscript was posthumously published, proved to be but a fragment of perhaps eight thousand words.29 Harlan Ellison lived prospectively, anticipating the completion and attending acclaim of works that seemed so real to him that he could not help exaggerating the particulars. He also lived anxiously, spending a quarter century promising the imminent delivery (and sometimes announcing the completion) of The Last Dangerous Visions before he finally declared he would no longer answer questions about it.

The final question is: How good would these novels have been, had Ellison been able to complete them? My guess is, not very good. Many were conceived around screenplays and teleplays, and Ellison’s scripts were always plot-driven, highly dramatic stories. However good they are as scripts (I am not qualified to judge), plot dynamics never played a large role in Ellison’s best fiction. Much of his best stories (the “Ticktockman,” “At the Mouse Circus,” “Eidolons,” “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore”) possess no dramatic arc, while the stories that execute plot twists and neat reversals are usually among his more facile works.

Ellison’s gift lay in his style, in the intensity of his imagery and the vividness of short, explosive scenes that at their best possessed an almost hallucinatory power. Stories in which multiple scenes happen in succession, joined by logical causality, were something that Ellison was surprisingly bad at. “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” (to take a celebrated story) comprises several short scenes that, save for the last one, could have taken place in any order. (And as Larry Niven once observed, the story’s climax relied on Ellison changing the rules about whether the evil computer could bring victims back from the dead.)

He worked best in electrically sharp prose that does not carry well into extended scenes. Those stories that venture much longer than 8000 words (the length of “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes”) tended to rely on routine dramatic structures, such as Ellison used — as he had to — for his Hollywood scripts.30

Short stories can be dreamlike, non-linear, poetic — the Ellison stories just cited earlier are all these — but a book-length narrative requires control over cause and effect, nuance in characterization, plausible motivation in secondary figures. Ellison could manage or finesse these within the formal constraints of Hollywood treatments and scripts — his screenplays and teleplays essentially follow templates — but not really otherwise.

None of his stories are notable for their dialogue. Ellison is a highly visual writer, and while his own voice is memorable in his prose, one rarely recalls things his characters said. His scripts, composed of dialogue and action, have little in common with his best stories, and efforts to convert them into prose fiction were foredoomed to failure. Edward Bryant was able to turn the teleplay of “Phoenix without Ashes” into workmanlike prose, but Ellison, had he imprudently sought to undertake the job himself, would probably have foundered. The “Blood’s A Rover” teleplay was written in 1977; Ellison was still preparing to “finish the whole novel” — that is, turn the script into prose — twenty-five years later in 2002.31

When, twelve years after that, Ellison was encouraged by editor Jason Davis to return to the project, he chose not to take up the task of adapting the teleplay that had so long defeated him, but rather to begin a new story. He managed to write a few pages of “Lying Doggo” before suffering a stroke that October.32

What would have come of this, and how much had Ellison managed to write of The Man Who Looked for Sweetness, we will never know.

Notes

- Ellison’s three published novels are Web of the City (1958), The Sound of a Scythe (magazine text 1959; 1960), and Spider Kiss (1961). (All were first published under different titles.) In addition, he published a number of novellas that, after their initial magazine appearances, were reprinted in book form, and his teleplay “Phoenix Without Ashes,” novelized in 1975 by Edward Bryant, was credited as a collaborative novel.

- “At MadCon, An Ailing Harlan Ellison Will Say Goodbye” by Josh Wimmer. Isthmus, September 23, 2010.

- Davis, Jason. “From ‘A Boy and His Dog’ to BLOOD’S A ROVER: Nearly Fifty Years in the Post-Apocalyptic Wastes.” In Blood’s A Rover by Harlan Ellison. Edgeworks, 2018.

- For example, James Blish’s 1972 novel Midsummer Century lists two titles, Beep and King Log, as “in preparation”; the latter was never published.

- See Jason Davis’s discussion in Brain Movies: The Original Teleplays of Harlan Ellison, Volume Three, p. 82.

- Headnote to “Try a Dull Knife,” The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1968, p. 70.

- These can be found in the front matter pages of the original editions of I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (Pyramid, 1967) and Love Ain’t Nothing But Sex Misspelled (Trident, 1968).

- I have not yet traced the issue in which this appeared.

- The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, July 1977, p. 4.

- Davis, Jason. “Editor’s Note: Life Isn’t a Fountain?” Brain Movies: The Original Teleplays of Harlan Ellison, Volume 5, 2013, p. 194.

- In conversation with Gregory Feeley, 1988. Jason Davis notes that RIF, outlined in 1971, was based on a proposed episode for a television series that Ellison had pitched two years earlier. Brain Movies: The Original Teleplays of Harlan Ellison, Volume Eight, p. 3. The outline for the episode, “Barbarian!” (clearly based on the life of Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian), is on pp. 65-66.

- When Pyramid published the paperback edition of Love Ain’t Nothing but Sex Misspelled in February 1976.

- Prior to its sale to Moorcock, the manuscript had been offered to Robert Silverberg and Harry Harrison, who both rejected it. See Silverberg, The Best of New Dimensions, p. 71, and Tomlinson, Harry Harrison: An Annotated Bibliography, p. 41.

- See, for example, “Harlan Ellison on the Art of Making Waves,” Twilight Zone, December 1981, p. 16. Available at archive.org/details/Twilight_Zone.

- Mitgang, Herbert. “Publishing: Bidding for Readers.” New York Times, August 29, 1980, p. C17.

- “Harlan Ellison on the Art of Making Waves,” Ibid.

- “Interview with Harlan Ellison” by Gary Groth. The Comics Journal #53, Winter 1980. Available at tcj.com/the-harlan-ellison-interview.

- “Harlan Ellison on the Art of Making Waves.”

- Debbie Notkin, in conversation.

- Locus, September 1981, p. 5.

- Ellison, Harland and Corben, Richard. Vic and Blood: The Chronicles of a Boy and His Dog. St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1989. Unnumbered final page.

- Ellison, Harlan. “Latest Breaking News: The Kid and The Pooch.” Available at bookscool.com/en/Vic-and-Blood-567248/1

- Wimmer, Ibid.

- Untitled web page at harlanellisonbooks.com/project/the-sound-of-a-scythe.

- Ellison, Harlan, ed. Again, Dangerous Visions. Doubleday, 1972, p. 744.

- Shellenbarger, Shane. “Neither Your Harlan Nor Mine: The Morning, Afternoon, and Two Evenings of Delicate Terrors.” Available at http://www.harlanellison.com/gallery/contributions.htm.

- When Ellison promised a short story for the program book of the 1978 World Science Fiction Convention (where he was Pro Guest of Honor), two staff members were compelled “to drive from Phoenix to L.A. to obtain said story after Harlan missed several deadlines with ever-more-colorful explanation. (He cooked them hamburgers and let them sleep overnight on his couch while he ‘put finishing touches’ on the story.)” See “Gary Farber’s Iguanacon II Reminiscence,” Fancyclopedia 3. Available at fancyclopedia.org/Iguanacon_II_Reminiscence_(Farber)

- Ellison, Harlan. “Last Words About Terry,” Terry’s World Beth Meacham. Tor Books, 1988, pp. 233-34.

- “Author’s Authors.” The New York Times Book Review, December 5, 1976, Page 5. Available at www.nytimes.com.

- The opening moment of “The Function of Dream Sleep,” in which the protagonist awakes to see a large mouth closing in his side, from which something immaterial escapes like a breath, is deeply and mysteriously beautiful; it is worthy almost of Kafka. It is much stronger than the rest of the novelette: Ellison simply asserts that his protagonist’s profound sense of loss is genuine (and others’ are superficial) and then moves his story towards an extended and routine conclusion.

- Ellison, Harlan. Brain Movies Presents Harlan Ellison’s Blood’s a Rover, 2019, p. 6.

- Davis, Jason. “From ‘A Boy and His Dog’ to BLOOD’S A ROVER: Nearly Fifty Years in the Post-Apocalyptic Wastes.” In Blood’s A Rover by Harlan Ellison. Edgeworks, 2018, p. 13.

I’ve read Web of the City and Spider Kiss. The first is very much a period piece, an immature work full to the brim with 1950’s NYC juvenile gang cliches, but I still found it energetic and readable. Spider Kiss, on the other hand, I thought was quite good. Its portrait of the demonically talented and completely immoral rock singer Stag Preston was melodramatic but effective, and Ellison’s overheated style suited the material. Of course, once Stag Preston was transmogrified into the vicious actor Frankie Fane in Ellison’s risible script for The Oscar, things went rapidly south.

I think you’re certainly right that Ellison’s talents made him better suited for sprints than for marathons.

Fascinating. I remember him being a big name when I was a teenager, but rarely coming across any of his stuff – I’m guessing because even by then the SF market was defined by books rather than short stories. Pretty long books, too.

Excellent piece — I’ve seen you expand a bit on Harlan’s novelistic ambitions and his failure to realize them before, but this essay is a really neat compendium of his entire history of announced and abandoned novels.

He truly had talent — as you say, best expressed at under perhaps 10,000 words — and while I know he was proud of his short fiction it’s rather a shame that he couldn’t fully embrace his identity as a short story writer and revel in that accomplishment.

Thought about this for a day then thought -why not? Years ago back in my Shadow pulp collecting days Ellison announced a graphic novel called Dragonshadows to be published by Fantagraphics for $5. I sent in the pre-order cost and waited. Michael Kaluta provided a cover and this was going to be wonderful which was previewed on the back of a Comics Journal. I think it would have been a fine tribute story. For the record I have only a read a story or two by Ellison as printed in the Saint Detective digests. What I HAVE always enjoyed by him are his straightforward pull no punches essays on all sorts of topics in books and primarily back in the Comics Journal in the 70s. I followed the libel lawsuit served against him by Michael Fleisher over comments made in the Comics Journal which totally agreed was meant as a compliment to any discerning reader when discussing Fleisher’s Jonah Hex and Spectre work. Ellison’s sympathy for the man after it was over was a true reflection of the man’s empathy for others. (Posted by an occasional fan of the site under the old name Allard).

Richard! Great to see you again. I was wondering what became of Allard — I always enjoyed your comments. Welcome back. 🙂

Many thanks for this article! I understand the reasons for Ellison’s unfulfilled desire to write novels as well as short stories, but I also find it unfortunate given the frustration it caused him. I agree completely with Rich’s remark: “it’s rather a shame that he couldn’t fully embrace his identity as a short story writer and revel in that accomplishment.” He could have followed the example of Borges (whom he so much admired), who never wrote a novel and who had the confidence to openly proclaim his preference for the short story form.

Thanks. I’d never run across that 1980 Mitgang piece referring to the plot of SHRIKES. After reading “Mefisto in Onyx” with its use of “shrike” I’d thought that the novella was what finally became of the never-completed novel.

[…] TITLE SEARCH. At Black Gate, Gregory Feeley finds that “The Fantastic Novels of Harlan Ellison” were more honored in the breach than the […]

My favorite clause from this excellent piece is this: “Harlan Ellison lived prospectively…”

I recently read several volumes of fannish history, and of course Ellison came out of fandom (“Seventh Fandom” apparently, though I’ve yet to be convinced that those numbers mean anything). I hesitate to relate this because I can’t put my finger on the passage, but there’s a paragraph or two of discussion of some fannish project Ellison announced he was undertaking (I think this is probably in Harry Warner, Jr.’s book about the 1950s) that never came to anything. The outlining of the particulars was skeletal, but it mapped onto Platt’s history of the Last Dangerous Vision in the blow-by-blow, as it maps on to this material.

I’ve never been the fan of Harlan Ellison (at any length, in any genre, fiction or non, filmed or unfilmed) that many of my peers and forebears were (mostly were, fondness for all things Ellison seems to fade with age)–I personally find all of his moves obvious, most of them painfully so, and most of them clumsily made. But neither can I deny the vitality and energy that MANY people obviously have taken and perhaps continue to take from his work.

So this is a welcome piece, though I do have a caveat. I don’t think, Greg, that you are a psychiatrist, and while it has been a tactic of historians and biographers for a long time now to offer up various diagnoses of their subjects, I’m not personally comfortable with it. Does it seem likely that Ellison had ADHD? I can’t say. Rather, I don’t believe I SHOULD say. He certainly exhibits behaviors that map onto some of my own, and yes, I have been diagnosed in a clinical setting with ADHD. But that doesn’t mean he suffered from the condition.

Anyway, not to distract from this otherwise excellent account, that’s just a matter of personal taste. Like my taste for Ellison’s work, I suppose!

[…] The Fantastic Novels of Harlan Ellison […]

Is Man With Nine Lives worth reading? Or should one buy Sound Of a Scythe?

The new version is not really very different from the old. Unless you are seriously interested in tracking the (very minor) revisions, either the magazine text, the original paperback, or the revised version are pretty much the same.