Vintage Treasures: The Hugo Winners, Volumes 1, 2 and 3, edited by Isaac Asimov

|

|

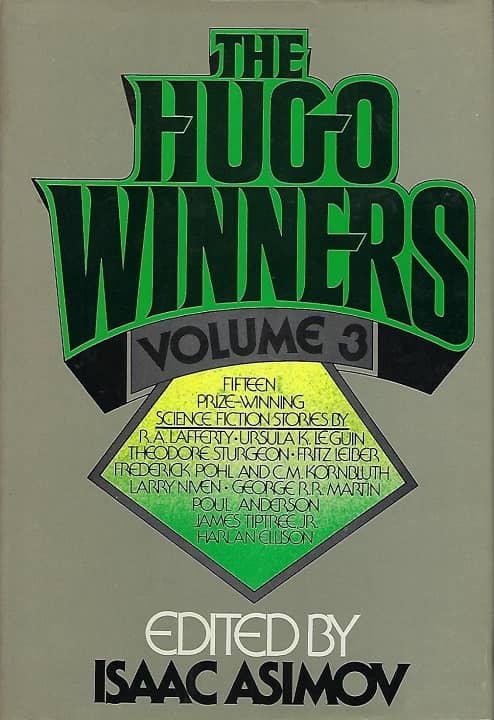

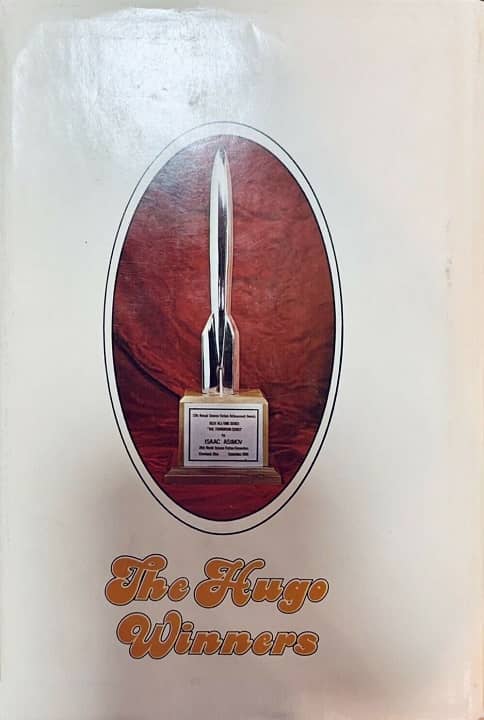

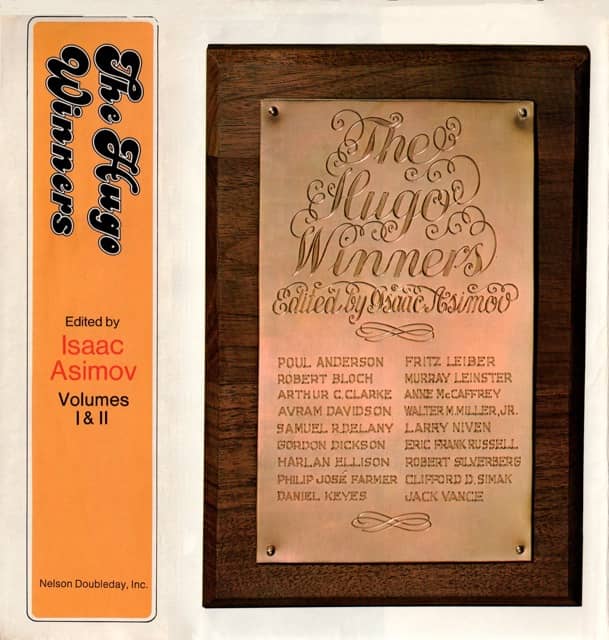

The Hugo Winners, Volumes I & II and The Hugo Winners, Volume 3 (Doubleday, 1972 and 1977).

Cover designs by F. & J. Silversmiths, Inc, and Robert Jay Silverman

I’ve written 1,973 Vintage Treasures articles for Black Gate. (That seems like a lot. Is it a lot? If it were, the paperbacks waiting to be written up wouldn’t be threatening to topple over in a spine-crushing avalanche, right? Still seems like a lot, somehow.) My Vintage Treasures pieces aren’t reviews, sometimes because it’s been so long since I’ve read the book in question that I don’t trust myself to do it justice — and sometimes because I haven’t read it at all.

But mostly because I know from experience it takes me forever to assemble a decently thoughtful piece on a book I really enjoyed (or really didn’t enjoy — that takes even longer). In the time it takes me to produce a review I’m happy with, I can write four or five chatty Vintage Treasures, and that seems like a fair trade.

I’m going to break with that tradition here to offer up at least a partial review of The Hugo Winners, the groundbreaking 1962 anthology edited by Isaac Asimov, and its two follow-up volumes, The Hugo Winners, Volume II (1971) and Volume III (1977), all published in hardcover by Doubleday. They are perhaps the most important SF anthologies ever published, and I’ve read them so many times I’m pretty sure I can talk about them entirely from memory.

[Click the images for Hugo-sized versions.]

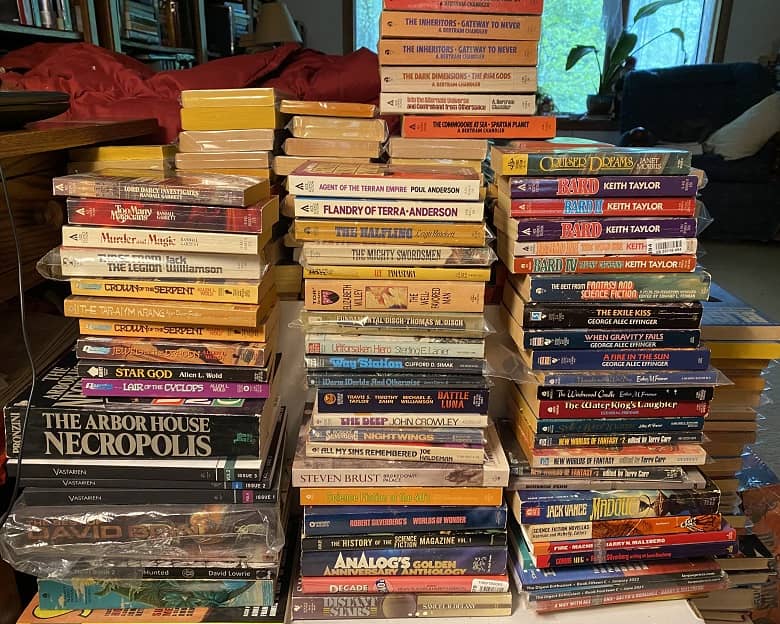

A few of the books piled next to my big green chair, waiting to be turned into Vintage Treasures

The Hugo Awards, of course, are voted on by science fiction fans and awarded every year at The World Science Fiction Convention. Since 1968 they’ve been given out in three categories for short fiction: Best Short Story (fiction under 7,500 words), Best Novelette (7,500 to 17,500 words) and Best Novella (17,500 to 40,000 words),

Back in 1998 Locus magazine, which knows its way around a poll, surveyed its readers on the Best All-Time titles in multiple categories. This was the result for Best Anthology.

- Harlan Ellison, ed., Dangerous Visions (Doubleday, 1967)

- Robert Silverberg, ed., Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One (Doubleday, 1970)

- Raymond J. Healy & J. Francis McComas, eds., Adventures in Time and Space (Random House, 1946)

- Harlan Ellison, ed., Again, Dangerous Visions (Doubleday , 1972)

- Isaac Asimov, ed., The Hugo Winners, Volumes 1 & 2 (Nelson Doubleday, 1972)

- Gardner Dozois, The Year’s Best Science Fiction (series, 1984-)

- Robert Silverberg, ed., Legends (Tor, 1998)

- Marion Zimmer Bradley, ed., Sword and Sorceress (DAW, 1984)

- Isaac Asimov, ed., Before the Golden Age (Doubleday, 1974)

- Ben Bova, ed., The Best of the Nebulas (Tor, 1989)

- Ben Bova, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Vol. 2a & 2b (Doubleday, 1973)

- Judith Merril, The Year’s Best SF (series, 1956-1968)

- Kirby McCauley, ed., Dark Forces (Viking, 1980)

- David G. Hartwell & Kathryn Cramer, eds., The Ascent of Wonder: The Evolution of Hard SF (Tor, 1994)

- Damon Knight, Orbit (series, 1966-1980)

- Andre Norton, Catfantastic (DAW, 1996)

- John W. Campbell, Jr., ed., The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology (Simon & Schuster, 1952)

- Robert Silverberg & Marta Randall, eds., New Dimensions (series, 1971-1981)

- Patrick Nielsen Hayden, ed., Starlight 1 (Tor, 1996)

- Patrick Nielsen Hayden, ed., Starlight 2 (Tor, 1998)

- Terry Carr, Universe (series, 1971-1987)

- James Gunn, The Road to Science Fiction (1998)

- Bruce Sterling, ed., Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology (Arbor House, 1986)

- various editors, Nebula Awards Stories (1966-)

- Robert Silverberg & Martin H. Greenberg, eds., The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction (Arbor House, 1980)

With all due respect to the learned readers of Locus, this list is hogwash. The best SF anthology of all time is obviously The Hugo Winners, Volumes 1 & 2 (followed closely by Before the Golden Age, but that goes without saying.)

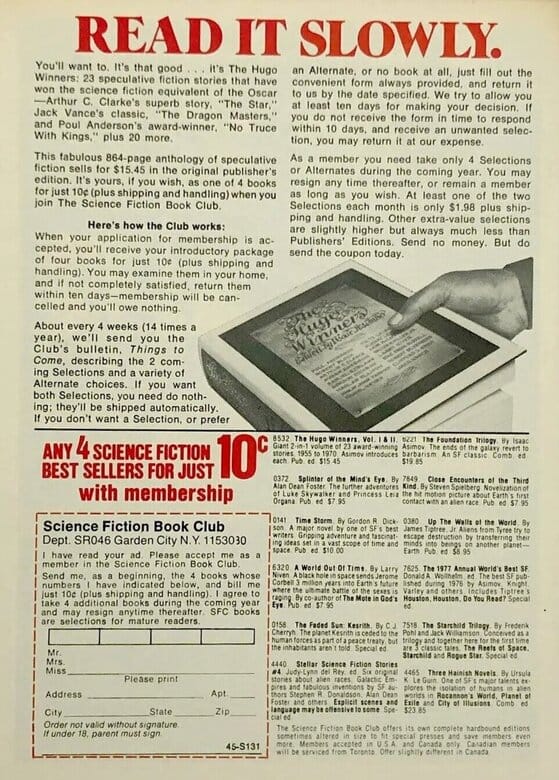

“Read it Slowly. You’ll want to…. it’s that good.” The classic Science Fiction Book Club ad featuring

The Hugo Winners (from the back of the premiere issue of Asimov’s SF Adventure Magazine, Fall 1978)

I ordered The Hugo Winners, Volumes I & II, like many thousands of others, as part of my introductory offer for the Science Fiction Book Club. It was 1977. I was thirteen years old, and living in Ottawa, Ontario. (The other two titles included in my intro offer, also written by or edited by Asimov, were The Foundation Trilogy and Before the Golden Age.)

The Hugo Winners, Volumes I & II was, of course, an omnibus volume of the first two Hugo anthologies published by the SFBC. I don’t have any hard stats, but just going by how long it featured prominently in SFBC ads (decades), I’m fairly confident it was one of the most popular titles ever published by the club.

In many ways, this was the book that introduced a generation to science fiction. That was certainly true in my case.

The omnibus volume includes stories from a veritable Who’s Who of mid-20th Century American SF: Walter M. Miller, Jr., Eric Frank Russell, Murray Leinster, Arthur C. Clarke, Avram Davidson, Clifford D. Simak, Robert Bloch, Daniel Keyes, Poul Anderson, Jack Vance, Gordon R. Dickson, Harlan Ellison, Larry Niven, Anne McCaffrey, Philip José Farmer, Fritz Leiber, Robert Silverberg, and Samuel R. Delany.

The Hugo Winners, with that iconic spine font

The stories include:

“The Darfsteller” by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

Ryan Thornier used to be a stage actor, in the days before they were replaced by robot mannequins. Now he works as a janitor in a theater. When he sabotages the tapes for the lead in an evening performance, he’s recruited at the last minute as a replacement. But the small improvisations and mistakes he makes on stage forces the master computer to make improvisations of its own…

A poignant tale of a man who learns you can never turn back progress, “The Darfstellar” is also a compelling character study of an aging creative who no longer has a place in the world. Buried cleverly underneath all of that, a story-within-a-story only partially revealed in snippets of on-stage dialog, is the fascinating play itself, the tale of a doomed love triangle that triggers the collapse of the Soviet Union. A masterpiece piece of SF storytelling

“Allamagoosa” by Eric Frank Russell

A classic slice of Golden Age science fiction, in which the cold steel corridors of spacegoing vessels look, smell, and sound just like the cramped below-decks quarters of enlisted men in the WWII Pacific Theater (and somehow feel all the more realistic for it). The crew of the deep-space vessel Bustler have a critical inspection coming up, and there’s one piece of equipment unaccounted for — an offog. What the heck is an offog? No one has a clue, but if they can’t produce one for the inspector, there will be consequences.

The resourceful crew quickly throw some unused parts together, and pass it off as the missing offog. They fool the inspector, and then quickly get rid of the thing with a fake service report. But their subterfuge proves to have far-reaching consequences… when the real offog shows up.

“The Big Front Yard” by Clifford D. Simak

Hiram Taine and his dog Towser live a pretty good life out in the country. Until Towser smells some strange critters in the walls, and starts digging frantically in the yard… and then the back of the house vanishes. Hiram finds the entire back wall of his home is gone, and the walls curve together to meet seamlessly.

At least, that’s the way it looks from the outside. Inside his home is totally normal, except his back porch now looks over an alien world. Setting out to explore with Towser, Taine finds other alien structures… and pretty soon, aliens (including a small pack of what looks like tiny alien engineers, walking off into the sunset after a job well done.)

Hiram is a completely normal guy in a completely unnormal situation, mankind’s sole ambassador in an unexpected First Contact. Hiram and Towser rise to the challenge stoically and with good humor, armed with Hiram’s one great gift — his ability to drive a hard bargain. It turns out to be just what the situation calls for. “The Big Front Yard” is one of the best first-contact stories ever written, and the antidote for anyone who finds modern SF too dark and humorless.

“Flowers for Algernon” by Daniel Keyes

Charlie is developmentally disabled, and works as a janitor. When an experimental technique turns him into a genius, his world rapidly turns upside down.

“Flowers for Algernon” is an absolute gut-punch of a story. Daniel Keyes wrote four SF novels and less than a dozen short stories, but nearly his entire reputation — and a very fine rep it is — rests on this one story. It was the basis for the 1968 movie Charly, which won lead Cliff Robertson an Academy Award.

“The Dragon Masters” by Jack Vance

Jack Vance was a master of gorgeously rich world building, and this short novel is a shining example.

The human settlers on the planet Aerlith breed alien dragons whom they ride into battle against the alien greph… who breed humans as slaves for much the same purpose. Joaz Banbeck, the descendant of the legendary Kergan Banbeck, who first captured the alien greph, tries to prepare his people for what he believes is an impending attack, while also coping with a devious human rival. Infighting leaves the humans woefully prepared for an attack that threatens to totally overwhelm the colony, and Banbeck find himself in a desperate battle to save what’s left of mankind.

Vance peopled his stories with fascinating aliens and equally fascinating and exotic human cultures, and set them on deeply interesting worlds. These isn’t anyone else like him, even today.

“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” by Harlan Ellison

Ellison’s post-apocalyptic tale of the last human survivors living inside a vast hostile computer is a crystalized nightmare. Each of the survivors has been psychological or physically maimed by the computer; the narrator believes (incorrectly) he is the only one left untouched.

After the latest in a sequence of unrelenting tortures devised by the machine, the humans find one last way to rebel, with unexpected results for the narrator.

Here’s the back covers for both books.

|

|

Back covers for The Hugo Winners, Volumes I & II and Volume III

In addition to the tales themselves, these volumes were famous for Asimov’s highly personalized introductions to each story. To a young teenage kid in Ottawa, Asimov’s chummy tales of the tight-knit American science fiction community somehow made writing science fiction seem like the most glamourous profession on Earth.

It was this book (along with The Early Asimov, which contained Asimov’s recollections of his early writing trials and successes) that made me dream of becoming a science fiction writer — a dream I eventually realized years later, when I published my first stories under the name Todd McAulty in Black Gate.

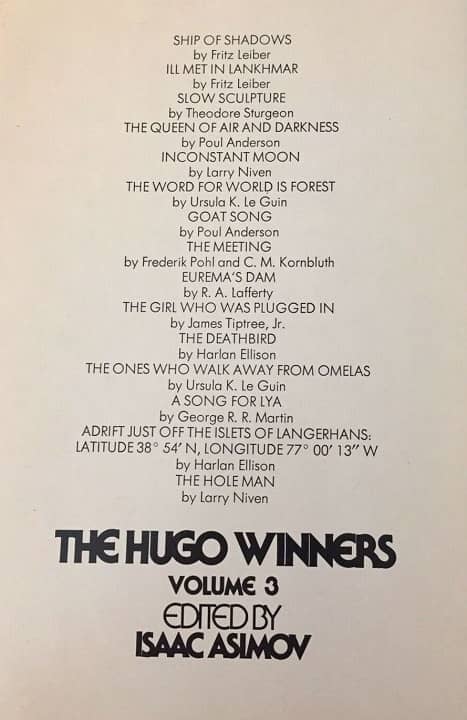

Here’s the complete Table of Contents for all three books (the first two are collected in one omnibus volume.)

The Hugo Winners, Volume One

Introduction by Isaac Asimov

“The Darfsteller” by Walter M. Miller, Jr. (Astounding Science Fiction, January 1955)

“Allamagoosa” by Eric Frank Russell (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1955)

“Exploration Team” by Murray Leinster (Astounding Science Fiction, March 1956)

“The Star” by Arthur C. Clarke (Infinity Science Fiction, November 1955)

“Or All the Seas with Oysters” by Avram Davidson (Galaxy Science Fiction, May 1958)

“The Big Front Yard” by Clifford D. Simak (Astounding Science Fiction, October 1958)

“The Hell-Bound Train” by Robert Bloch (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, September 1958)

“Flowers for Algernon” by Daniel Keyes (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, April 1959)

“The Longest Voyage” by Poul Anderson (Analog Science Fact -> Fiction, December 1960)

Postscript by Isaac Asimov

Appendix: The Hugo Awards

|

|

|

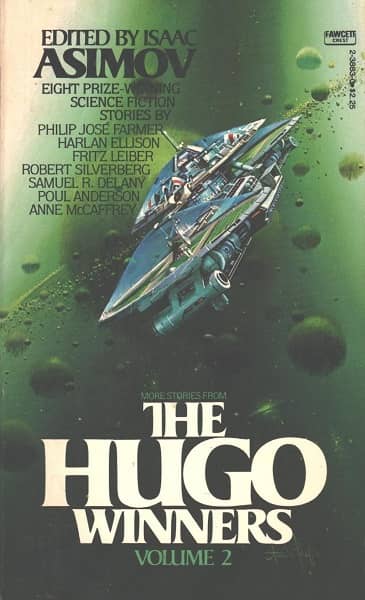

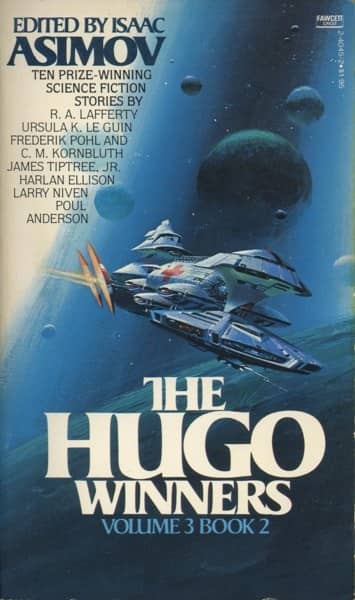

1979 Fawcett Crest paperback editions. Covers by Attila Hejja

The Hugo Winners, Volume Two

Here I Am Again, by Isaac Asimov

“The Dragon Masters” by Jack Vance (Galaxy, August 1962)

“No Truce with Kings” by Poul Anderson (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, June 1963)

“Soldier, Ask Not” by Gordon R. Dickson (Galaxy, October 1964)

“Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman” by Harlan Ellison (Galaxy, December 1965)

“The Last Castle” by Jack Vance (Galaxy, April 1966)

“Neutron Star” by Larry Niven (If, October 1966)

“Weyr Search” by Anne McCaffrey (Analog Science Fiction -> Science Fact, October 1967)

“Riders of the Purple Wage” by Philip José Farmer (Dangerous Visions, 1967)

“Gonna Roll the Bones” by Fritz Leiber (Dangerous Visions, 1967)

“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” by Harlan Ellison (If, March 1967)

“Nightwings” by Robert Silverberg (Galaxy, September 1968)

“The Sharing of Flesh” by Poul Anderson (Galaxy, December 1968)

“The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World” by Harlan Ellison (Galaxy, June 1968)

“Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” by Samuel R. Delany (New Worlds, December 1968)

Appendix: Hugo Awards 1962-1970

The Hugo Winners, Volume Three

Introduction: Third Time Around, by Isaac Asimov

“Ship of Shadows” by Fritz Leiber (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, July 1969)

“Ill Met in Lankhmar” by Fritz Leiber (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, April 1970)

“Slow Sculpture” by Theodore Sturgeon (Galaxy, February 1970)

“The Queen of Air and Darkness” by Poul Anderson (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, April 1971)

“Inconstant Moon” by Larry Niven (All the Myriad Ways, 1971)

“The Word for World Is Forest” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Again, Dangerous Visions, 1972)

“Goat Song” by Poul Anderson (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, February 1972)

“The Meeting” by C. M. Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, November 1972)

“Eurema’s Dam” by R. A. Lafferty (New Dimensions II, 1972)

“The Girl Who Was Plugged In” by James Tiptree, Jr. (New Dimensions 3, 1973)

“The Deathbird” by Harlan Ellison (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1973)

“The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin (New Dimensions 3, 1973)

“A Song for Lya” by George R. R. Martin (Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, June 1974)

“Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Latitude 38° 54′ N, Longitude 77° 00′ 13″ W” by Harlan Ellison (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1974)

“The Hole Man” by Larry Niven (Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, January 1974)

Afterword by Isaac Asimov

|

|

|

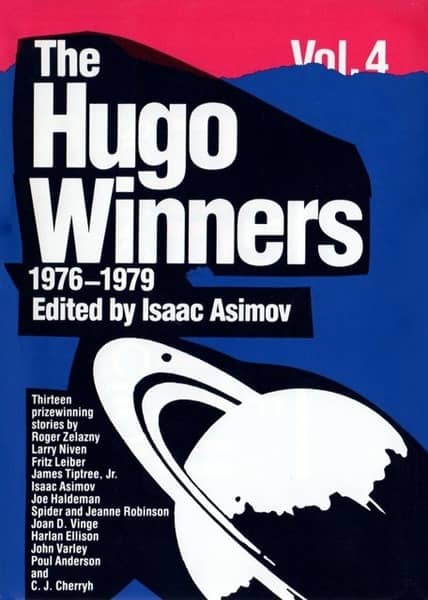

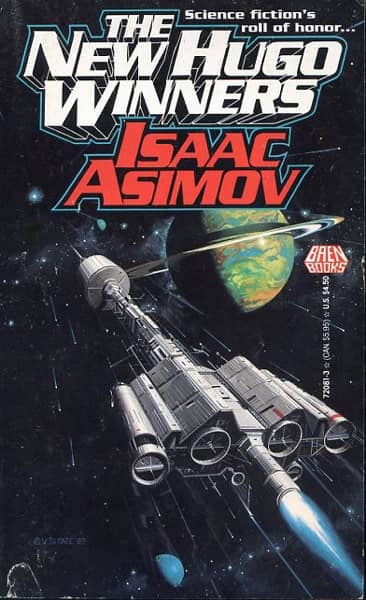

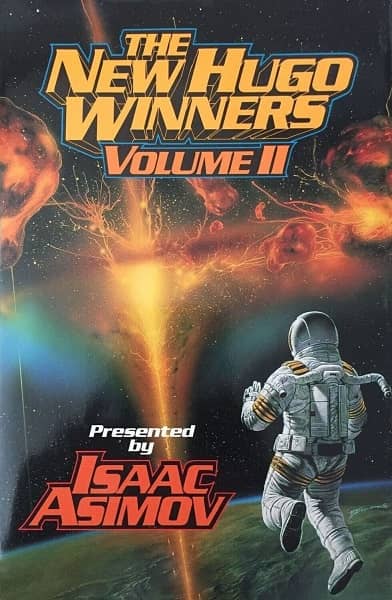

The Hugo Winners, Volume 4 (Doubleday, 1985), The New Hugo Winners (Baen, 1991) and

The New Hugo Winners Volume II (Baen, 1992). Covers by Kiyoshi Kanai, Vincent Di Fate, and Bob Eggleton

Asimov eventually produced eight volumes of Hugo Winners (nine if you count the Science Fiction Book Club omnibus edition of the first two). Here’s the complete list, with links to our coverage so far.

The Hugo Winners (Doubleday, 318 pages, $4.50 in hardcover, 1962) — cover uncredited

The Hugo Winners, Volume Two (Doubleday, 667 pages, $9.95 in hardcover, September 1971) — cover by Alan Peckolick

The Hugo Winners, Volumes One and Two (SFBC, 849 pages, $3.98 in hardcover, January 1972) — cover by F. & J. Silversmiths, Inc.

The Hugo Winners, Volume Three (Doubleday, 622 pages, $12.50 in hardcover, August 1977) — cover by Robert Jay Silverman

The Hugo Winners, Volume 4 (Doubleday, 575 pages, $19.95 in hardcover, April 1985) — cover by Kiyoshi Kanai

The Hugo Winners, Volume 5 (Doubleday, 384 pages, $18.95 in hardcover, April 1986) — cover by Tita Nasol

The New Hugo Winners (Wynwood Press, 320 pages, $17.95 in hardcover, December 1989), edited by Isaac Asimov with Martin H. Greenberg — cover by Britt Taylor Collins

The New Hugo Winners, Volume II (Baen, 375 pages, $4.99 in paperback, January 1992), edited by Isaac Asimov with Martin H. Greenberg — cover by Bob Eggleton

The Super Hugos (Baen, 424 pages, $4.99 in paperback, September 1992) — cover by Frank Kelly Freas

After Asimov’s death in 1992, Connie Willis and Gregory Benford edited two additional volumes for Baen.

The New Hugo Winners, Volume III (1994) edited by Connie Willis

The New Hugo Winners, Volume IV (1997), edited by Gregory Benford

I hope to cover all ten anthologies in future Vintage Treasures posts here.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Great overview!

Re: your photo of the forthcoming Vintage Treasures piles–I own quite a number of those books, and am so going to look forward to seeing your take on some of them!

Thanks Lou! At the rate I write these articles, it’s going to take many years to get through them all.

Let me know if there are any you’d like me to get to first. 🙂

I love the A. Bertram Chandler John Grimes space operas, so they get my vote. Several years ago when Baen came out with six enormous omnibus volumes collecting them all, I snapped them up even though I already had most of the books in old Ace editions. You know how it is…

Thomas — I didn’t even know about those! I just found all six on Amazon, and they look terrific. Most of them are still available in mass market. I’ll order a couple today, and make sure to feature them in the article.

Thanks!

The SFBC published hardcover versions of collected Chandler too, John, and there are 6 in that set, published from 2000-2005. I have all those, plus the paperbacks shown above, and for the most part, both the Baen pbs and the SFBC hardcovers have the same overall contents, though arranged differently and with differently titled volumes. It’s been a while since I looked through them, but I think the Baen and the SFBC each have a few things the other doesn’t. The SFBC volumes are listed on the ISFDB under “John Grimes, SFBC Set.”

Smitty,

I forgot all about the Science Fiction Book Club versions!

For the most part I actually prefer the SFBC covers, too. I hadn’t realized they were organized differently. Something else for us collectors to obsess over. 🙂

The Grimes sequence is torture for me, obsessed as I am with reading things in sequence – do I read the books as they were published or do I follow the two different “internal chronologies” in the series? Aarghhh!

I am a sucker for a good spaceship picture, so would definitely go for the Fawcett versions if i could lay my hands on them. So many great stories.. I see that Allamagoosa made it. The one story that seems to come up in so many anthology. I got curious, went to ISFDB, 81 instances of this story published in various forms. If my count us correct.

Wow…. 81 reprints! You can see how, if you were prolific and good enough, it was possible to make a living as a short story writer in the middle of the 20th Century. One good story could continue to bring in a tidy income stream for decades.

And I know exactly what you mean about those Attila Hejja covers on the Fawcett versions… I’ve been trying to gather a complete set for years! They are lush and evocative of old-school space adventure.

Well, I learned we have tow things in common from this post, John. I also got The Hugo Winners and the Foundation Trilogy in my SFBC intro order, although it was a few years later. I had to get Before the Golden Age in a 2nd hand shop. It was no longer offered by the club.

I’ve also got most of the books in the photo.

Great minds think alike!

I knew you were a man of discerning taste, Mister West! 🙂

Just based on how long the SFBC kept THE FOUNDATION TRILOGY (with that classic chessboard cover) and THE HUGO WINNERS in print, I sometimes think half of the people who joined had them in their club sign-up package.

Glad to hear you’ve also got most of the books in that photo. Which ones should I start with?

That’s a tough question. I’m partial to Anderson, Williamson, Simak, Brackett, Effinger, and Garrett. Any of Terry Carr’s anthologies would also be good.

I have separate stacks for Terry Carr’s BEST SCIENCE FICTION OF THE YEAR and his hardcover 70s anthologies (there’s a LOT of them). It’s probably a fantasy to think I’ll get to most of them, but they certainly deserve the attention.

I got the same books when I joined, and they’re still on the shelf. What a terrific post! Sometimes it seems to me those were the great days of SF!

Thanks R.K. I’ve been meaning to do this one for a while.

It’s easy to be blinded by nostalgia, and miss out on the great work being done by talented new writers — and I saw that happen all the time in the 80s, with some older fans I knew stubbornly insisting that science fiction had gone downhill since the 50s — but there are times when I find myself falling into the same mindset, especially when I look over all those great anthologies from the 70s and 80s.

I wouldn’t give up all the amazing progress the field has had since, and I’d be an idiot to ignore the fantastic stuff being written today. But that era truly was a wonderful time for the genre.

They’re the same books I got too – I guess we’ve pretty conclusively carbon-dated ourselves, huh fellas?

I can’t remember two thirds of the classes I took in college, or name a single text book. But I recall every detail of the introductory package from the SF Book Club — including how wonderful they smelled. 🙂

What was your third book, Thomas?

I think it was the two volume Treasury of Great Science Fiction; if you want to take that set away from me, you’ll have to pry it from my cold, dead hands, if only because that’s the first place I read Alfred Bester and The Stars My Destination.

Excellent choice! I had to buy the set as a full-price selection. And it was absolutely worth it.

These books deserve a Vintage Treasures entry all of their own.

The Mystery Book Club offered a two volume Treasury of Great Mysteries; I’ve always wanted to pick those up.

I just reread this fabulous post, and while doing so was struck by some things. First, my sign-up for SFBC was years before the back cover you show. Hmmm. I was a subscriber to Astounding SF beginning 1950, and no doubt took the plunge that decade or just after. I kept that subscription through the mid-Eighties.

Oh! How I remember those issues coming in the mail, those fabulous covers! How I wish I still had those issues today. Sigh.

I scrupulously preserved and collected every issue of the Science Fiction Book Club’s newsletter, THINGS TO COME, since I joined in 1976. But they vanished when I moved to Illinois in the early 90s.

I assumed they were still in my parents’ basement in Ottawa. I made several searches for them over the years, and when we cleared out my parents house for good last year I spent hours sorting through junk in the basement looking for them with no luck (though I did find a big box of vintage 1970s Marvel Comics buried under a ton of junk, so it wasn’t wasted effort!)

You and I aren’t the only folks who still wish we had those old newsletters, Smitty. They command some high prices on eBay! If I could have replaced my old issues I would have, but they’re well out of my price range.

I still hope I’ll find mine someday. 🙂

I also got that Hugo Winners anthology as part of my introductory package for the SFBC. My second book was Again, Dangerous Visions, and I’m not sure about the third — maybe the package of The SF Hall of Fame, Volume IIA and IIB.

That was really a great way to be introduced to short SF — early stuff, mid period stuff, and “new for then” in the Ellison anthology. (Now 50 years old, alas!)

And, yes, I loved all of Asimov’s chatty introductions — in the Hugo books, and in The Early Asimov, and in Before the Golden Age …

Rich,

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame volumes were a fantastic choice. Even back then, it’s clear you had good taste! 🙂

Just a pedantic little correction: The three short fiction categories became standard only in 1973, not 1968. The years 1970 – 1972 reverted to only two short fiction categories (novella and short story), but there has been complete consistency since 1973 (provided of course we ignore the occasional overrun of the relevant word counts). Since 1973 the Hugos and Nebulas have had the same short fiction categories.

Right you are Piet. That was sloppy Hugo research on my part.

Thanks for the correction!