A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘Pulp Repurposed – They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?‘

Fellow Black Gater Thomas Parker and I have been exchanging our thoughts on the various topics covered here in this column. I mentioned Horace McCoy’s Jerry Frost, head of Hell’s Stepsons, sort of a Seals team for the Air Texas Rangers (also fictional). McCoy is, of course, best-known for his novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?. Which I’ve never read. Nor have I seen the movie. So, I asked Thomas. if he’d like to write a guest post on that book. And boy, did he! Read on.

Fellow Black Gater Thomas Parker and I have been exchanging our thoughts on the various topics covered here in this column. I mentioned Horace McCoy’s Jerry Frost, head of Hell’s Stepsons, sort of a Seals team for the Air Texas Rangers (also fictional). McCoy is, of course, best-known for his novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?. Which I’ve never read. Nor have I seen the movie. So, I asked Thomas. if he’d like to write a guest post on that book. And boy, did he! Read on.

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” — Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

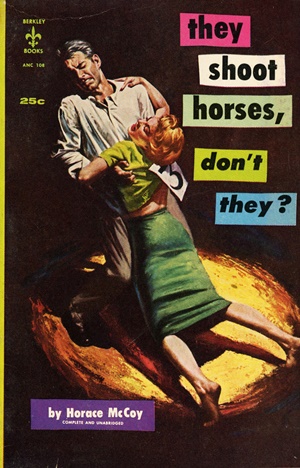

A while back our own Hardboiled Bob Byrne gave us a run-down of the May, 1934 issue of Black Mask, which featured a story by Horace McCoy, a writer whose fame rests solely on his 1935 novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? which probably more people know from the fine 1969 film version starring Jane Fonda than from actually having read. McCoy’s novel is an ambitious piece of work, and with it he was clearly seeking to extend himself beyond the boundaries of commercial pulp – and yet, the mark of Black Mask and its ten and fifteen cent brethren is everywhere in the book. In They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, pulp atmosphere and pulp devices are deployed, but with a deadlier intent than any found in the pages of Dime Detective. Call it pulp repurposed.

In what amounts to a manifesto for the American pulp style, Raymond Chandler famously declared (in his 1944 essay, “The Simple Art of Murder”), that Dashiell Hammett had started the ball rolling because he

gave murder back to the kind of people who commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not with hand-wrought dueling pistols, curare, and tropical fish. He put these people down on paper as they are, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily use for these purposes.

In other words, Hammett and those who followed him were realists, in both style and substance – at least as compared with proponents of the unbearably artificial (in Chandler’s estimation, anyway) English school like Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, and the American S.S. Van Dine, the creator of amateur sleuth Philo Vance, dismissed by Chandler as “the most asinine character in detective fiction.”

If the American pulp style praised by Chandler consists of realistic characters with realistic motives using realistic means to commit crimes in contemporary urban settings, then They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? must be considered a prime example of the form, even more so than Chandler’s own Philip Marlowe stories, with their stainless hero and romantic patina.

A story of crime it undoubtedly is; it is not, however, a mystery in the conventional sense, because we know from the first page that Robert Syverten killed Gloria Beatty, shooting her in the head as they sat next to each other on the Santa Monica pier. The only mystery is — why?

The novel is nothing less than the answer to this question in the form of Syverten’s confession. Robert begins his account of the weeks leading up to the murder by portraying himself as an optimistic young man who’s trying to break into movies as an extra, but who hopes to ultimately be a director (The great names of the era – Von Sternberg, Mamoulian, Borzage – are always on his lips and in his thoughts). One day outside Paramount Studios, he meets Gloria, an aspiring actress. Neither of them is having much – or any – luck storming the gates of Hollywood, so at Gloria’s instigation they decide to enter one of those staples of depression-era America, the dance marathon.

The last couple standing will split a thousand dollars (a tidy sum in 1935), along with receiving free food and a free bed as long as they last. In addition, Gloria tells the initially reluctant Robert that producers and directors often attend the marathons, looking for fresh talent for the pictures. Robert finally agrees to be Gloria’s partner. It’s a fatal decision, and, like most such, goes unrecognized at the time.

The marathon turns out to be a torturous, brutal ordeal. The set up couldn’t be simpler:

The rules were you danced for an hour and fifty minutes, then you had a ten-minute rest period in which you could sleep if you wanted to. But in those ten minutes you also had to shave or bathe or get your feet fixed or whatever was necessary.

The relentless grind quickly wears the contestants down; the contest begins with one hundred and forty-four couples, and sixty-one drop out during the first week. Feet and legs swell and bleed, unwashed bodies reek, stress causes tempers to fray, fistfights and knifings break out on the dance floor, and mental and physical exhaustion lead to disjointed and irrational thinking, and even to outright paranoia.

It’s all made worse by the cynicism of the marathon’s promoters, who are always on the loudspeakers bellowing hearty exhortations and encouragements full of fake praise and solicitude for these “wonderful kids.” Their exploitative priorities become apparent (not that there was ever any doubt) when they decide that attendance can be boosted — and the pack of remaining contestants thinned – by staging a race (a sort of roller derby without skates) each evening, with the last place couple to be eliminated from the competition.

It’s all made worse by the cynicism of the marathon’s promoters, who are always on the loudspeakers bellowing hearty exhortations and encouragements full of fake praise and solicitude for these “wonderful kids.” Their exploitative priorities become apparent (not that there was ever any doubt) when they decide that attendance can be boosted — and the pack of remaining contestants thinned – by staging a race (a sort of roller derby without skates) each evening, with the last place couple to be eliminated from the competition.

When one contestant is recognized as an escaped killer and is hauled off the floor by detectives, the promoters are delighted; it’s great publicity, and they follow this unexpected boon by persuading a couple to get married during the dance. (In the midst of the depression, a hundred dollars could be a great persuader.) It’ll increase interest in the contest and the pair can always get divorced afterwards. Life and show biz at the marathon (and by implication, in the society that spawned it) – it’s all the same. Since this is the case, it’s only natural that as the contest gains in notoriety, film people actually do start to show up to watch, though needless to say, no drooping dancer ever gets pulled out of this purgatory to star with Garbo – or even with Rin Tin Tin.

Finally, after 879 hours, a murder occurs at the bar that’s attached to the dance hall and the marathon is shut down. The promoters give each of the twenty remaining contestants fifty dollars. Everyone wins… and everyone loses.

Robert and Gloria walk outside for the first time in over a month. They sit at the edge of the continent, that ultimate dead end, and look at the sunset over the ocean… and Gloria takes a pistol out of her purse and asks Robert to kill her, which he does. Why? Because he was her friend – he was her only friend.

Robert and Gloria walk outside for the first time in over a month. They sit at the edge of the continent, that ultimate dead end, and look at the sunset over the ocean… and Gloria takes a pistol out of her purse and asks Robert to kill her, which he does. Why? Because he was her friend – he was her only friend.

Throughout the story, Gloria has been a bitter hater of life, or at least a hater of the kind of life that is the only one that she will be permitted to live, and her rage at the emptiness of her existence is only exacerbated by the unrelenting stress of the contest. For her, the only escape from this abyss is death, and this conviction colors everything that she says and everything that she does. Robert describes her as “morbid,” and it’s an understatement.

Believing that life is a trap, Gloria tries her best to persuade a pregnant fellow contestant to have an abortion; she spews obscenities at fellow dancers, contest officials, and even well-wishers in the audience; she loses no opportunity to denigrate and destroy the hopes of every person she comes in contact with, Robert’s most of all. With her continual talk of suicide (her most characteristic and oft-repeated words are, “I wish I were dead”) Gloria is the embodiment of the bleak, bottom-of-the-barrel, breadline nihilism of the darkest days of the depression, and she doesn’t so much convince the friendly, sunlight-loving Robert that her hopeless view of life is correct as she catches him with his defenses decimated by his five week ordeal and fatally infects him with it.

Gloria’s philosophy was probably not completely shared by Horace McCoy (he neither shot himself nor persuaded anyone else to do it for him, instead dying of a heart attack in 1955), but her loathing of the world she found herself in is conveyed with an intensity that seems too strong to be nothing more than a literary device. Certainly, the book mounts a searing and deeply felt critique of the callousness, hypocrisy, vulgarity, and shallowness of American society, especially in its California iteration. In the dance marathon, where you never stop moving and yet never get anywhere, McCoy found his perfect metaphor for the cruel void that he saw in 1930’s America.

In this, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? is one of a group of distinguished, bitter books that see Hollywood – and Los Angeles, the pustule that surrounds it – as hell on earth, the Epicenter of ‘All That’s Wrong,’ the spot of mold that relentlessly spreads out to corrupt and spoil the whole loaf: Nathaniel West’s The Day of the Locust, John Fante’s Ask the Dust, Aldous Huxley’s After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, and Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One. These books were all products of the bleak 30’s and the chaotic 40’s, but McCoy’s novel came before any of them and in that sense is truly prophetic.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? differs from these other books, not in its acid vision or sour diagnosis of a patient already dead, but in its origins; it’s the only one to emerge from a pulp sensibility rather from an overtly “literary” one, and it kicks all that harder for that.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? differs from these other books, not in its acid vision or sour diagnosis of a patient already dead, but in its origins; it’s the only one to emerge from a pulp sensibility rather from an overtly “literary” one, and it kicks all that harder for that.

McCoy’s novel is obviously more seriously intentioned than his stories for the crime pulps, not least in its lack of a conventional hero and in a downbeat ending that solves nothing but only reinforces the meaninglessness and absurdity of what’s gone before. He also employs a startlingly effective device that he likely couldn’t have used in a commercial magazine story: the book’s chapters come in between the words of the judge’s sentencing speech. The first page contains nothing but the judge’s first words: “THE PRISONER WILL STAND.” Between the first and second chapter the judge says, “IS THERE ANY LEGAL CAUSE WHY SENTENCE SHOULD NOT NOW BE PRONOUNCED?” It continues this way until the end, with each between-chapter pronouncement in all capitals, and each one in larger and larger type until, on the last page of the novel, the final seven words take up the entire page: “…MAY GOD HAVE MERCY ON YOUR SOUL…”

The device is simple but the effect is powerful, not least in reinforcing our knowledge that Robert’s fate is already sealed and that there is nothing that he can do or say to change it. The inexorable march of the sentencing speech is like the striking of a great bell, tolling louder and louder until the final, deafening note. It greatly contributes to the atmosphere of doom and fatality that pervades the book.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? has great literary distinction, as the editors of the Library of America recognized when they included it their volume Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930’s and 40’s, but pulp fingerprints are on every page. Here are the realistically gritty people Chandler extolled, living in a recognizably real world of everyday things and everyday events, and acting in natural ways that are shaped by the constraints of their character rather than dictated by the needs of an unreal plot.

And within that commonplace story of down-on-their-luck people trying to grab a little money and fame in a dance contest, McCoy told a tale as brutal in its way as any Black Mask yarn of a back-alley bootlegger’s brawl or tabloid tommy-gun massacre. The novel is filled with lightening-quick outbursts of violence, not all of it emotional (One of the contest emcees keeps order on the floor by using a blackjack on obstreperous contestants. Race Williams or the Continental Op couldn’t have done any better).

But perhaps the place where They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? shows its pulp allegiance most clearly is in its language, especially the dialogue, which is as realistic and unembellished as could be. In one amazing scene, Gloria confronts two censorious ladies from The Mother’s League for Good Morals and fires off a salvo that would lay Miss Marple out with apoplexy and compel Hercule Poirot to jump off the Orient Express:

“Do you ladies have children of your own?” Gloria asked, when the door had closed.

“We both have grown daughters,” Mrs. Higby said.

“Do you know where they are tonight and what they’re doing?”

Neither woman said anything.

“Maybe I can give you a rough idea,” Gloria said. “While you two noble characters are here doing your duty by some people you don’t know, your daughters are probably in some guy’s apartment, their clothes off, getting drunk.”

Mrs. Higby and Mrs. Witcher gasped in unison.

“That’s generally what happens to the daughters of reformers,” Gloria said. “Sooner or later they all get laid and most of ’em don’t know enough to keep from getting knocked up. You drive ’em away from home with your god**** lectures on purity and decency, and you’re too busy meddling around to teach ’em the facts of life —”

“Why —” Said Mrs. Higby, getting red in the face.

“I —” Mrs. Witcher said.

“Gloria —” I said.

“It’s time somebody got women like you told,” Gloria said, moving over and standing with her back to the door, as if to keep them in, “and I’m just the baby to do it. You’re the kind of bitches who sneak in the toilet to read dirty books and tell filthy stories and then go out and try to spoil somebody else’s fun —”

“You move away from that door, young woman, and let us out of here!” Mrs. Higby shrieked. “I refuse to listen to you. I’m a respectable woman. I’m a Sunday School teacher —-”

“I don’t move a ******* inch until I finish,” Gloria said.

“Gloria —”

“Your Morals League and your god**** women’s clubs,” she said, ignoring me completely, “—filled with meddlesome old ******* who haven’t had a lay in twenty years. Why don’t you old dames go out and buy a lay once in a while? That’s all that’s wrong with you….”

Mrs. Higby advanced on Gloria, her arm raised as if to strike her.

Go on — hit me,” Gloria said, not moving. “Hit me! —You even touch me and I’ll knock your ******* head off!”

It goes downhill from there.

It’s hard to know where you would get a scene remotely like that in 1935, if it weren’t in the pulps or in the few books by writers who weren’t afraid to be influenced by them. There’s certainly nothing like it in Goodbye, Mr. Chips or Gone With the Wind, two of the typical bestsellers of the era, and it’s not just that the language is radically different, it’s that the language is necessary because McCoy is reporting on an entirely different world than the one that produced most other books.

The raw-edged pulp magazines of the 30’s had a powerful (if unacknowledged, at least at the time) and generally beneficial effect on American literature, as They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? demonstrates. It wouldn’t be the novel that it is without the work that Horace McCoy did in the pulps and the lessons in sharp, unsentimental, pared-to-the-bone storytelling that he learned from it. His great, ferocious novel reads like it was written by a hungry man in a hurry, for no-nonsense people who didn’t have a minute to waste; just like they do, it knows the score. Once in motion, the story moves with all the unstoppable momentum of a steel safe pushed down an elevator shaft, and when you turn the last page, with the sentence of the judge still echoing in your head, you may just feel as if you’re the one the safe has landed on.

Just like a lead-shot sap to the back of the neck.

Previous entries in the series:

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife.

Bob Byrne’s A (Black) Gat in the Hand appears weekly every Monday morning at Black Gate.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March 2014 through March 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!). He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

I read this novel in the LOA volume that you mention. Though definitely of the same mood as the other novels in that book, it also struck me as completely different. It’s clearly “noir”. But calling it a “crime” novel seems like a stretch to me, at least as that genre is usually understood. I think it fits better with the existentialist and nihilist novels of later years, like Camus, Sartre, and Kafka. So, in that sense, McCoy’s book is prophetic and ahead of its time.

I liked this book, it was definitely an interesting read. But it’s also very dark and in a very depressing way. It’s not the sort of book I would recommend to someone who is going through a rough time. That being said, it definitely does not deserve to be forgotten.

Thanks for giving this book (and the movie, which I’ve never seen) due time and thought.

I agree, James – it’s not really a “crime” book within any but the most elastic definition of the term. Horses most resembles – though it came first – The Day of the Locust, especially as both books have a low view of the mental and moral character of the average American and are equally critical of the “entertainment industry”.

I’ve never read this, and the film is middling at best (or at least so it was for me), but it’s worth noting that in between the novel and the film (1969), along came a play called Marathon 33 (1963), written by June Havoc, the one and only sister of Gypsy Rose Lee. It traverses the exact same terrain, is often indistinguishable from They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? and simply doesn’t work on its feet. Revivals have been attempted, mostly to poor reviews. My own experience with it suggests that while a novel can have some fun exploring the dancers’ interior states, the stage version is forced to depict the tedium of the whole affair––of literally dancing ’til you drop––and that tedium wears off on the audience.

Great article, Thomas. I’m not familiar with the book, but of course I’ve heard the title.

Any idea why McCoy wrote only a single novel? He seemed to have a gift for it.

He did write a few others, John – they just weren’t nearly as successful (artistically or commercially) as Horses.