A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams – Black Knight, Cannibal and Forgotten Man

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

If you read Pulp, you know who Evan Lewis is. He’s an MLB MVP while I’m AAA on a good day. Hardboiled, Adventure, Doc Savage, Dick Tracy, Davy Crockett, Nero Wolfe – the guy knows it all. He and I message about our like interests, and I conned – I mean, convinced – him to join in the Black (Gat) parade, this year. I know a little about Cleve Adams, but not nearly enough to write about the once popular but now mostly forgotten pulpster.

Chapter 1

OBSCURITY

Cleve F. Adams is the forgotten man among hardboiled pulp writers. Though he produced well over a hundred stories and more than a dozen novels, almost every word is now out of print.

Adams was an anomaly in that his characters were genuinely hardboiled, while his style was not. His detectives were sometimes harder and more brutal than their contemporaries, but remained likable due to his easy-going whimsical style. This blend of violence and humor made him one of the relatively few hardboiled pulp writers to successfully move his magazine characters into hardcover.

Chapter 2

HONESTY

Little is known of Cleve Adams’ early life. What we do know is merely what he and his publishers chose to say in “About the Author” notes. Nevertheless, it’s interesting stuff, and some of it might even be true.

Adams was born in Chicago in 1895, where he attended the Hamilton Business Institute before heading for California. Over the next 15-odd years, he did almost everything but write. Among his many occupations were: soda-jerk, section hand, window trimmer, interior decorator, motion picture art director, copper miner and life insurance executive. When not otherwise occupied, the legend goes, he supported himself as a private detective.

Adams did a lot of traveling, some of it by thumb, and was once thrown in jail. This was proven an injustice, he said, but the cops did not apologize. Somewhere along the way he met a lady named Vera, whom he married. They had one son. W.T. Ballard, in his interview with Steve Mertz (The Armchair Detective Winter 1979), recalled meeting Cleve and Vera in 1931, when they were running a candy store in Culver City. They did well enough to open more candy stores and fancied himself, for a time, a “chain store executive.” But, he later told Argosy, “The Board of Trade caught up with me along in ’32 or ’33, and I was tired of being honest, anyway, so took up writing professionally.”

Chapter 3

THE FAT LADY

By 1933, the first wave of hardboiled pulp writers was subsiding.

Dashiell Hammett was gone and Raoul Whitfield going. The biggest names still working the field were Frederick Nebel, who stuck until 1937, Carroll John Daly, and Erle Stanley Gardner.

Adams came in on the second wave, along with Raymond Chandler, Richard Sale, Cornell Woolrich, Norbert Davis, W.T. Ballard, Robert Leslie Bellem, Frank Gruber and George Harmon Coxe.

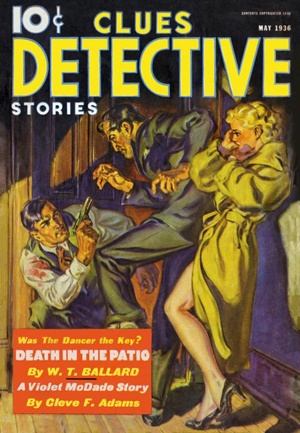

I wish I could tell you where Adams made his first sale. The earliest piece I’ve located is in the November, 1933 issue of Street & Smith’s Clues Detective Stories. In any case, Clues is where Adams first made his mark as a mystery writer, and he did it with a fat lady.

Violet McDade, a carnival exhibit turned detective, appeared in Clues as early as January, 1935 and soon became one of the magazine’s headliners. Over the next three years, she starred in over a dozen stories. Violet is blustery, jovial, rambunctious, lusty, uncouth, ill-mannered and ungrammered. Yet, because her agency handles investigations for most major department stores and insurance companies on the West Coast, she’s afforded ample opportunity to shock members of polite society.

Violet McDade, a carnival exhibit turned detective, appeared in Clues as early as January, 1935 and soon became one of the magazine’s headliners. Over the next three years, she starred in over a dozen stories. Violet is blustery, jovial, rambunctious, lusty, uncouth, ill-mannered and ungrammered. Yet, because her agency handles investigations for most major department stores and insurance companies on the West Coast, she’s afforded ample opportunity to shock members of polite society.

Like many Adams heroes to come, Violet is seldom allowed to forget she came from the wrong side of the tracks. The friction between a low-born detective and upper-class clients would become an increasingly important element of Adams’ stories.

Violet’s adventures are narrated by her junior partner, Nevada Alvarado. Nevada is young, attractive and possessed of all the social graces, but she too is an outcast—by race. Even Violet, her closest friend, calls her Nevada only when she wants something. Otherwise, it’s “Mex.”

The similarities between Violet McDade and Nero Wolfe are impossible to ignore. Adams was not above borrowing a good idea when he saw one, and it’s possible he was influenced by the first Wolfe novel. Fer-de-lance was published both in magazine and hardcover in October 1934, three months before Violet made her debut.

Violet is of Wolfean proportions. She normally weighs in at 350, occasionally ballooning up to 400. Like Wolfe, she “waddles.” Nevada, when annoyed, refers to her as a lummox, and elephant or an overstuffed Buddha.

Like Archie Goodwin, Nevada finds plenty in her boss to annoy her. Violet often keeps things from her just so she can show off with a flashy finish. When Violet is thinking, her eyes acquire a dreamy, far-away look that prompts Nevada to complain, “They seem to be seeing things I’m not big enough to see.” Nevada is typical of Adams heroes to come in her conviction that among all creatures, she is the most sorely tried, and is often tempted to throttle her employer.

Of course, several things about Violet are decidedly un-Wolfean. She revels in profanity, her favorite expression being “Hell’s Bells,” and delights in telling tales of her “none too savory” past. She flaunts her bad taste by making her limousine driver wear a gaudy scarlet and gold uniform. In short, she continues to be a circus attraction.

As for her appetite, I submit the following:

“We’ll eat in our rooms,” says Violet. “Coupla New York cuts, medium hash-browns, a few knick-knacks to fill in the corners an’ plenty of coffee. What’re you gonna eat, Nevada?”

“I want,” Nevada says firmly, “four rye highballs and plenty of cigarettes. And privacy.”

Violet McDade is one tough dame. While other pulp dicks might slip .22s up their sleeves, Violet has room for a brace of .45s. She carries them always, even under her pajamas, and spends most of her spare time practicing their materialization. She’s “faster than a rattlesnake,” and loves an excuse to start slinging lead. And after a kill, she’s hardboiled as they come. After gunning down a lady murderer, Violet deliberately steps on her rather than walk around.

The series was a success for Adams, and he kept it going until late 1937, when he shifted his efforts to Double Detective and Detective Fiction Weekly.

Chapter 4

THE ANTI-HERO

Adams had built himself a name in Clues, but it was in the Munsey magazines he would develop the style and character to carry him into hardcover. It took only eighteen months.

From September, 1937 to March, 1939, Adams turned out more than twenty stories, several of which were short novels. Most were told in third person rather than first. Adams was discovering that he, himself, could tell a story better than his characters.

Though Adams’ detectives have many names, most share the same description (dark complexioned with gleaming white teeth), same personality (surly and aggrieved), same drinking habits (heavy and often), same relationship with the police (hatred and mistrust), same taste in friends (cab drivers and bellhops), and the same taste in clothes (camel’s hair overcoat and Borsalino).

On the surface, the typical Adams detective is a cynical anti-hero with a grudge against society and a certainty Fate is out to get him. A mercurial guy, he often gets mad, makes a fool of himself and says things he doesn’t mean, then broods over troubles of his own making. Unlike the stoic Sam Spade or virtuous Philip Marlowe, his first care is usually for his own creature comforts. But on the positive side, he’s honest, generous to a fault, and fiercely loyal to those he admires.

On the surface, the typical Adams detective is a cynical anti-hero with a grudge against society and a certainty Fate is out to get him. A mercurial guy, he often gets mad, makes a fool of himself and says things he doesn’t mean, then broods over troubles of his own making. Unlike the stoic Sam Spade or virtuous Philip Marlowe, his first care is usually for his own creature comforts. But on the positive side, he’s honest, generous to a fault, and fiercely loyal to those he admires.

The Adams hero chases women, but only as far as they want to be chased. The women he falls are modeled on Hammett’s Nora Charles. They’re bright, witty, born of the upper-crust, and make him wish he’d led a better life. And like Nora, they insist on playing detective. He knows such women are too good for him, and whenever marriage looms its ugly head, he escapes by behaving like a heel.

A stock element of Adams’ stories is a temporary sidekick/drinking partner for the hero. He helps McBride in some tasks, but more often just helps him get into trouble. Another stock element is a deadly dame who cozies up to the detective for nefarious purposes. Somehow, the hero’s inamorata always manages to walk in on one of the cozier moments and get her nose out of joint.

Unlike the near-mythical lone-wolf private eye, the Adams hero usually holds a more mundane position, like an insurance investigator, treasury agent or police lieutenant. Good and bad on many levels, the Adams hero comes off as a real man doing a real job in a slightly unreal world. It’s only Adams’ breezy storytelling that prevents him become a very serious character.

Adams’ third-person style is smooth and laconic, with a rhythm every writer should envy, and never fails to slap a smile on my face. Though hard-bitten, Adams’ prose is not truly hardboiled. Rather than masking his feelings in objectivity, the storyteller is clearly enjoying himself. He’s amused by his hero’s attempts to cope with a cockeyed universe. And he’s more of a gentleman than his protagonist, implying he is not responsible for the actions of his characters. This lets readers identify with the narrator, allowing a degree of attachment when the hero does something they find objectionable.

The Adams hero has been compared and contrasted to Raymond Chandler’s knight, Philip Marlowe, usually unfavorably, and none more unfavorably than Adams’ standard bearer, Rex McBride.

Chapter 5

THE BLACK KNIGHT

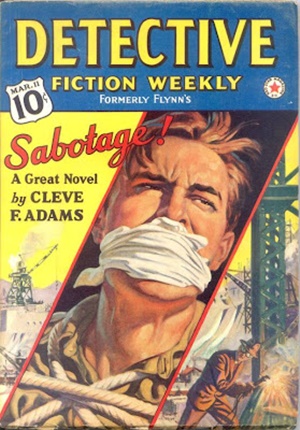

Adams’ first novel, Sabotage, appeared as a five-part serial in Detective Fiction Weekly, beginning March 11, 1939. Setting the story a mining town, Adams borrowed the basic plot from Hammett’s Red Harvest and fleshed out the background from his own experience as a copper miner. Like the Continental Op, McBride belongs to the dynamiting school of detection, lighting fires under everyone to see who blows.

Adams has been criticized for this “borrowing,” but I heartily approve. At least he borrowed from the best. Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars did the same, and they’re both great films.

Two more McBride serials followed. “Homicide: Honolulu Bound,” later published as And Sudden Death, began December 16, 1939 and Decoy kicked off on January 1, 1941. By mid-1941 all three novels had been published in hardcover, and the comparisons to Chandler’s knight began.

McBride is more complicated than Marlowe. As the supreme Adams hero, he projects the image of self-serving, womanizing brute. To his credit, most of his negative qualities are a sham but he clings to them so fiercely we are sometimes in doubt. The heel image becomes such a habit that giving in to his finer impulses feels like a compromise, making him genuinely angry. When caught doing something heroic, he brags about his accomplishments in an attempt to belittle them.

McBride is more complicated than Marlowe. As the supreme Adams hero, he projects the image of self-serving, womanizing brute. To his credit, most of his negative qualities are a sham but he clings to them so fiercely we are sometimes in doubt. The heel image becomes such a habit that giving in to his finer impulses feels like a compromise, making him genuinely angry. When caught doing something heroic, he brags about his accomplishments in an attempt to belittle them.

Through all his adventures, McBride is man who’s never quite comfortable in his skin. He wear expensive clothes and drinks good liquor (or any other kind), but never forgets his roots. Having come up from the gutter, he’s more at home with barflies and petty grifters than with folks in his own income bracket. He has nothing but contempt for the insurance execs and captains of industry who employ him. They’re phonies who pretend to have clean hands, but hire McBride to do their dirty work for them.

McBride is so deceptive he almost fools himself. A womanizer, he makes a pass at every female who crosses his path, but the moment one responds he finds himself backpedaling furiously. Despite his cavalier manner, he is incapable of taking advantage of an innocent girl. When one actually offers herself to him, he sets her straight and sends her home at his own expense.

McBride claims to be out for himself and no one else, but the first time we see him with a lot of dough he blows it on a party, inviting all his lower-class acquaintances to a ritzy hotel. His girlfriend accuses him of showing off, and is correct up to a point. The showing off (two bands and mountains of food) masks his generosity and genuine compassion for the cab drivers, gamblers and stool pigeons he considers his people. He’s uncomfortable with too much money, and can’t seem to spend it fast enough. As usual, his good intentions are camouflaged by anti-social methods.

McBride professes disdain for the military’s pre-war effort, but his actions in And Sudden Death expose him as a patriot. Working on an insurance case, he uncovers a Japanese spy ring and risks collecting a huge to help break it up. Caught in an unselfish act, he protests loudly and at length, exaggerating his sacrifice and sneering at government agents for not doing their jobs.

Deep down, McBride wants to be good but has to look bad doing it. That can’t be easy. It’s a strange sort of modesty, and might even be called knightly.

Adams first three novels had been written as complete works and broken into pieces for serialization. With MacBride a success, and publishers eager for more books, Adams followed the example of his friend Raymond Chandler and began “cannibalizing” his pulp work.

Chapter 6

THE CANNIBAL

Adams continued his pulp writing into mid-1942, finding acceptance with other magazines—including Black Mask—but then dropped out to focus on his novels. He apparently embraced Chandler’s cannibalization technique with such abandon that it would require a spreadsheet and a complete collection of his pulp stories to sort it all out. Sadly, my collection is far from complete, so I can offer only spotty evidence.

The 1941 novel The Black Door starred narcotics agent James J. Flagg, who had appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly as early as September 9, 1939 with “Contraband.” The only reason I know that story was not part of The Black Door is that it later became the middle third of the novel Contraband (1950), as discussed below.

The 1941 novel The Black Door starred narcotics agent James J. Flagg, who had appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly as early as September 9, 1939 with “Contraband.” The only reason I know that story was not part of The Black Door is that it later became the middle third of the novel Contraband (1950), as discussed below.

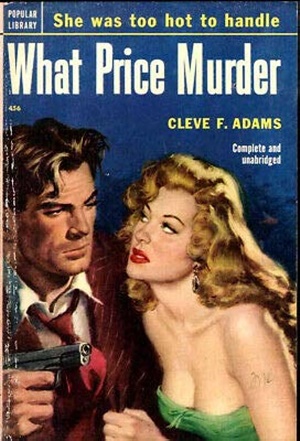

The 1942 What Price Murder featured police Lt. Steve McCloud, who appeared in DFW as early as October 2, 1937 in “The Private War,” a story I have not examined.

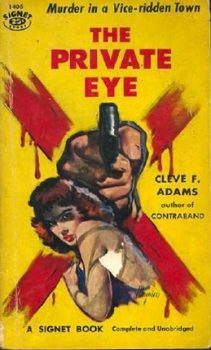

The Private Eye, also published in 1942, starred John J. Shannon, a veteran of at least two pulp stories, “Jigsaw” in DFW June 11, 1938 and “Mannequin for a Morgue” in Double Detective December, 1938. This is another variation on Red Harvest, in which Shannon takes control of both the union local and the town newspaper to bring things to a boil.

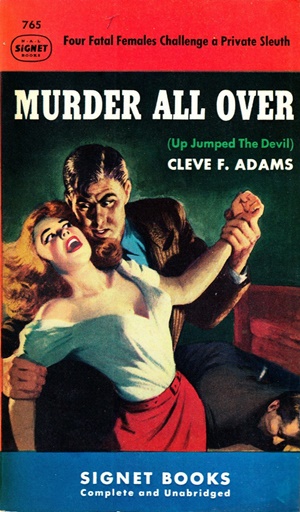

The first third of the fourth Rex McBride novel, Up Jumped the Devil (1943), began life as the January 13, 1940 DFW novelette “Exodus,” featuring a McBride clone a named Regan. Some of the supporting cast retained their names from the magazine story, while others were rechristened.

The lead in The Evil Star (1944) is Lt. Steve “McCord,” and features the same supporting cast as What Price Murder, making it likely the story grew from Steve McCloud pulp stock. McCord’s attempts to untangle a mess involving a set of beautiful triplets results in what I consider Adams’ funniest novel.

The two earlier “John Spain” books, Dig Me a Grave (1942) and Death is Like That (1943), feature Bill Rye, a character inspired by Hammett’s Ned Beaumont from The Glass Key. I suspect they, too, had their roots in pulp stories, but can’t prove it.

Likewise with the fifth Rex McBride book, another spin on Red Harvest called The Crooking Finger (1944). If anyone can offer clues to help sort this stuff out, they’d be much appreciated.

Chapter 7

ASSISTANT CANNIBALS

Adams had eleven novels to his credit when he mysteriously ceased production in 1944. He had done pretty well in the reprint market, with all of his books redone in either paperback or digest. But after the paperback edition of The Crooking Finger in 1946, he dropped out of sight.

Ironically, the one and only resurgence of interest in his work came shortly before his death. Mickey Spillane was proving sex and violence could sell a lot of paperbacks, and while Adams’ books only hinted at sex, they contained enough violence to be in step with the times.

Thanks to Mr. Stephen Mertz, who got the lowdown from Vera Adams, we know that Adams wanted to build his DFW novelette “Contraband,” from September 9, 1939, into a novel. When his health began to fail, he hired his friend Robert Leslie Bellem to do it for him.

Bellem had experience at this. Back in 1941, he had expanded Adams’ “Song of Hate,” from the August 1939 Double Detective, into the novel The Vice Czar Murders, published as by “Franklin Charles.”

Bellem had experience at this. Back in 1941, he had expanded Adams’ “Song of Hate,” from the August 1939 Double Detective, into the novel The Vice Czar Murders, published as by “Franklin Charles.”

Sadly, in December 1941, Adams suffered a heart attack and died before Contraband was published. For some reason, either Bellem or Adams changed the hero’s name from John J. Flagg to Reed Smith.

Bellem had been mimicking Adams’ style in a series of “Little Jack” Horner stories running in Hollywood Detective and Speed Detective, and did a decent job of masking his work. He showed his hand, though, when it came to sex. While Adams’ heroes did a fair amount of rough kissing, the action stopped there. In Contraband, Bellem allows characters to discuss the subject more freely than Adams ever had.

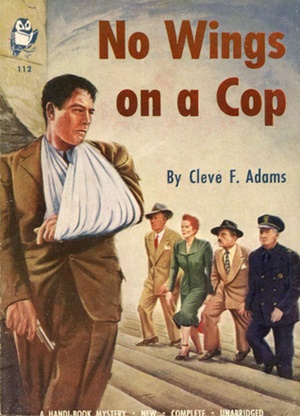

As a favor to Mrs. Adams, who needed financial assistance, Bellem also constructed the paperback original No Wings on a Cop (1950). This one was based on “Help! Murder! Police!” a three-part serial that began in the February 4, 1939 Argosy. Bellem couldn’t resist inserting himself into the story as bank clerk Robert B. Leslie, and showing a cabbie reading a comic book starring Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective.

Prior to his death, Adams had apparently been working on one last Rex McBride novel. An early version of this, titled “Too Fair to Die” appeared in Two Detective Books in March 1951. Who had a hand in that one is unclear, but a more polished version, completed by the writing team of Bellem and W.T. Ballard, appeared in 1955 as Shady Lady. Bellem and Ballard had a lot of experience working together, having produced several Jim Anthony novels for Super-Detective. At one point, McBride sees in the paper that an Ohioan named Ballard has won a fantastic radio jackpot and that a lady named Bebe (Bellem’s wife) Washburn has eloped with an Oreville blacksmith named Robert B. Leslie.

Sadly, the Adams revival did not last much longer. Only one book, The Private Eye, remained in print into the ‘70s, likely due to its ultra-generic title.

Chapter 8

THE BAD RAP

Google “Cleve F. Adams” today and you’re sure to turn up thirty-year-old references to Rex McBride being called a “racist” and a “fascist.” That’s a shame, because those words are not fair descriptors of either the author’s or the character’s body of work.

In short, those words are dynamite, and I believe they might have tainted the impressions of mystery fans who have not read him for themselves. Worse, I fear they may have deterred some who might otherwise have sought out and enjoyed his work.

First, the racism. By today’s politically correct standards, most detective writers of the pulp era—including Adams’ friend Raymond Chandler—were guilty of using racial slurs. In fact, I submit that the casual racism found in Chandler’s stories and novels is more extreme than those of Adams. If we damn Adams, we much damn Chandler as well.

I would like to think readers today are more understanding of this situation than those of thirty years ago, when those incendiary buzzwords were employed. As Tom Roberts noted in many of his Black Dog collections:

These stories are a reflection of the time period and accepted ideal of the era in which they were written. This book contains language and opinions that some readers may find objectionable.

If Rex McBride went farther than the norm in the use of racial slurs, it was part of his character. In keeping with his perceived persona as a rude and insensitive heel, he often spoke in heat, exhibiting a freewheeling contempt for anyone he didn’t like—whether of his own race or any other. In some cases, the use of slurs was even deliberate, meant to provoke anger. There’s no indication McBride hates anyone because of race—he hates them because of who they really are, and is not shy about using any derogatory terms that comes to hand to say so.

If Rex McBride went farther than the norm in the use of racial slurs, it was part of his character. In keeping with his perceived persona as a rude and insensitive heel, he often spoke in heat, exhibiting a freewheeling contempt for anyone he didn’t like—whether of his own race or any other. In some cases, the use of slurs was even deliberate, meant to provoke anger. There’s no indication McBride hates anyone because of race—he hates them because of who they really are, and is not shy about using any derogatory terms that comes to hand to say so.

In at least two cases, Adams exhibited finer racial sensibilities than many of his contemporaries. Because he spent much of his life in California, his Latino characters—beginning with Nevada Alvarado—are finely drawn. Many of his heroes, too, have spent time south of the border and speak fluent Spanish.

And in the novel And Sudden Death, despite Rex McBride’s travails battling a Japanese spy ring, his first encounter with a Japanese character runs counter to stereotype. McBride appreciates the fact the man is not at all obsequious, and wishes others could appreciate it too. He likes the guy so well he invites him to shoot craps. Even later, when the two become adversaries, McBride retains his respect for the man.

The “fascist” charge stems from a scene in the novel Up Jumped the Devil. As McBride attempts to recover a stolen necklace, he’s once again embroiled with spies and saboteurs, and a young girl he admires is tortured to death. Frustrated by the FBI’s inability to help, McBride turns the tables on the killer, having him tortured into making a confession. Afterwards, McBride is sickened by what he’s done, though he still feels justified.

That’s nothing Jack Bauer wouldn’t have done on 24. In fact, Bauer did much worse. The problem is that Adams allowed McBride to utter one line of unfortunate dialogue. When an FBI agent objects to what he calls McBride’s “Gestapo treatment,” McBride responds, “An American Gestapo is goddam well what we need.”

Taken out of context, that damning, but it’s a good example of McBride saying something he doesn’t really mean. In the context of the story, he’s merely advocating that the government fight fire with fire when dealing with saboteurs during wartime. McBride was subjected to the third degree by overzealous cops far too often (about which he complained bitterly) for him to endorse a police state.

Chapter 9

THE VERDICT

Though Adams’ plots were chaotic and sometime repetitive, his serio-comic style and unpredictable detectives made him one of the more popular mystery writers of his day. His development of the hardboiled anti-hero paved the way for many other less-than-knightly detectives who flourished in fifties and continue to flourish today.

Sadly, all of Adams’ novels are long out of print, and very few of his pulp stories have been reprinted. He deserves to be rediscovered. On the plus side, low demand means that much of his work is available at reasonable prices. I guess that’s something we can thank his critics for.

BOB NOTE – Evan and I both write intros for Steeger Books. Steeger has reissued Sabotage in hardback, softback, and digital.

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (4)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (8)

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (19)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

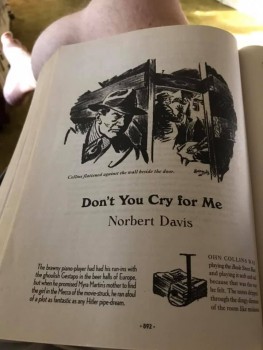

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

Evan Lewis – This Jim Bowie lookalike was the proud recipient of the Mystery Writers of America 2011 Robert L. Fish Award for his EQMM story “Skyler Hobbs and the Rabbit Man.” His AHMM story “The Continental Opposite” was nominated for a Shamus award and selected for Best American Mystery Stories 2016. His novel CROCKETT’S DEVIL was published last year by Steeger Books, and a follow-up, BOWIE’S GOLD has just been released.

Check out his terrific blog here.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

In searching for more information on Mr. Adams, I found the Prabook (World Biographical Encyclopedia) entry for him that says he “has been described as the missing-link between Dashiell Hammett and James Ellroy”. I cannot say if Mr. Adams is as deadpan as Mr. Ellroy, but that is a comparison intriguing enough for me to want to find one (or more) of Mr. Adams’s works. Thank you, Mr. Lewis, for the examination of this forgotten writer.

Also, according to Prabook, we need to fix one line in the article: “Sadly, in December 1949 (not 1941), Adams suffered a heart attack and died”.

One correction: Adams’s terrific novel Sabotage is currently in print courtesy of Steeger Books (who also publishes Evan Lewis’s own novels). https://steegerbooks.com/shop/sabotage-the-argosy-library-cleve-f-adams/

Noted. Thanks!

Excellent article, Bob, as always!

That’s all Evan! I think I’ve read maybe two Adams stories. You know me – bring in people who know more than I do, to write a good essay for me!

🙂

I’m currently working on essays about: Frederick Nebel’s Garrison air stories; review of a cool and Lam book; a Quarry book; a Solomon Kane story, and a Jim Thompson novel.

Too many things started – not enough completed!