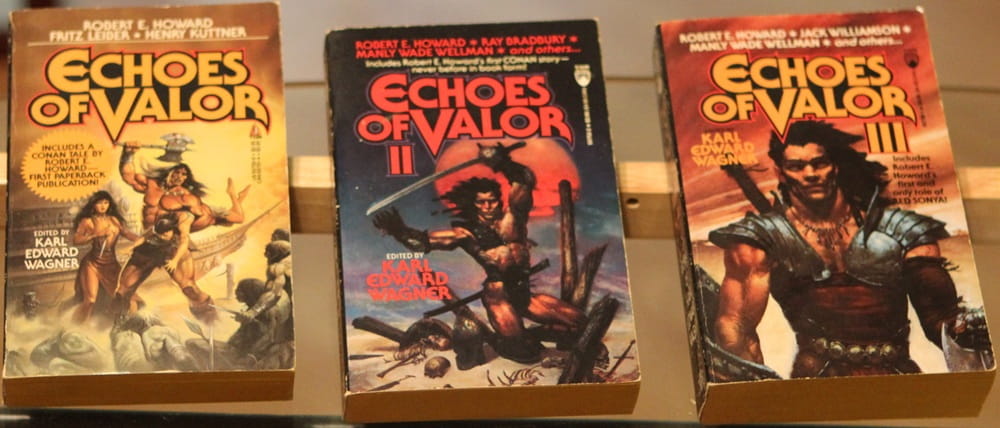

Classics of Sword & Sorcery: Echoes of Valor, edited by Karl Edward Wagner

The three book Echoes of Valor anthology series from TOR was edited by Karl Edward Wagner, who wrote excellent Sword & Sorcery tales himself, and could recognize good ones when he saw them. These were not anthologies of new stories, but reprints. Each contained a Robert E. Howard tale. Here are some capsule reviews.

Echoes of Valor (1987, Cover Ken Kelly)

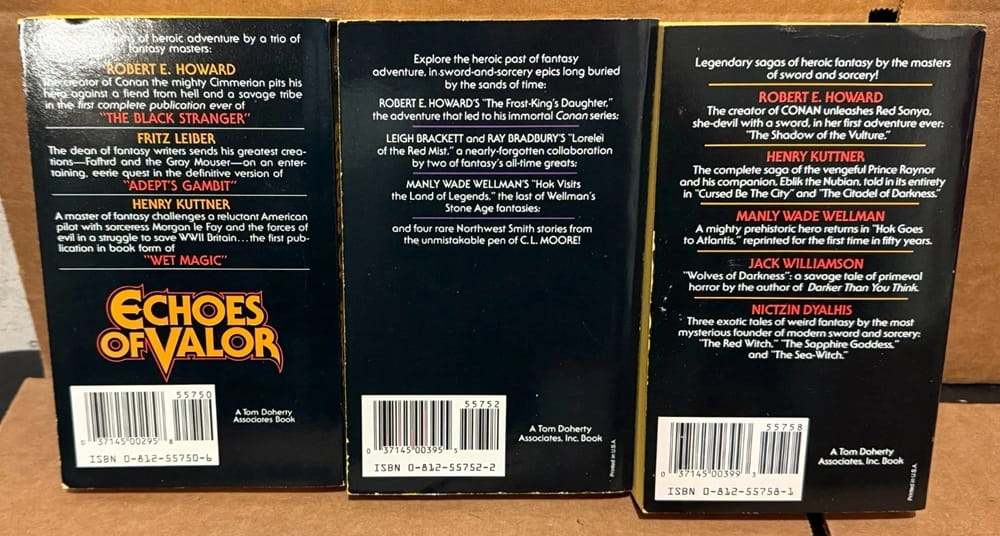

Contains one story each by Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, and Henry Kuttner. Howard’s story is “The Black Stranger.” It’s a Conan tale but wasn’t published in REH’s lifetime. He rewrote it as a pirate tale featuring Black Vulmea called “Swords of the Red Brotherhood.” It still didn’t sell. Long after Howard’s death, L. Sprague de Camp rewrote it as “The Treasure of Tranicos” and it was published. It didn’t really need the rewrite in my opinion, so who knows why it wasn’t published initially.

Leiber’s story is “Adept’s Gambit,” starring his two usual rogues; Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. It’s one of the best tales in the series. Kuttner’s story is “Wet Magic,” which I also enjoyed. It has Nazis, swords, and sorceresses. What more could you ask for?

Echoes of Valor II (1991, Cover Sam Rakeland, aka Rick Berry)

Contains stories by Howard, C. L. Moore, Manly Wade Wellman, and a collaboration by Leigh Brackett and a young Ray Bradbury. REH’s stories are “The Frost-King’s Daughter” and “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter,” which are variants of the same story featuring Amra (King’s) and Conan (Giant’s).

The four stories by Moore, all involving Northwest Smith, were excellent. The Brackett/ Bradbury story was even better. The complete Wellman story was “Hok Visits the Land of Legends.” I found it pretty weak. There was also a Hok Fragment that was much better. If you were being introduced to Wellman, this might not have been the way to do it.

Echoes of Valor III (1991, Cover Sam Rakeland)

Stories by Howard, Kuttner, Wellman, Jack Williamson, and Nictzin Dyalhis. Howard’s story is the only authentic Red Sonya story, “The Shadow of the Vulture,” which has always been a favorite of mine. Kuttner’s stories are the only two he did about a character named Prince Raynor, who lived during a time when the Gobi Desert was the seat of a civilization. Both are good. “Hok Goes to Atlantis,” by Wellman, was better than the Hok story in Echoes of Valor II, but not outstanding.

“Wolves of Darkness” by Jack Williamson was quite good, though it could have been shortened. Dyalhis was represented by three short tales, “The Red Witch,” “The Sapphire Goddess,” and “The Sea-Witch,” each of which was excellent. These stories definitely made me look for more by this author. There’s also a nice introduction on Dyalhis by Sam Moskowitz. Dyalhis was a mysterious character, and one worth digging into I think. I’ll post more about him eventually.

Folks here at Black Gate have dug into Echoes of Valor over the years; those articles are here:

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for us was an obituary for Heroic Historicals: Robert E. Howard, Harold Lamb, Poul Anderson and James Clavell. See all of his recent posts for Black Gate here.

Here is a series that completely escaped my attention back in the day. Checking the volumes, it looks like each one has something that would be new to me. Thank you (or curse you!), Mr. Gramlich.

Manly Wade Wellman is remembered, at least in part, because Wagner was a personal friend, who championed him over the years. However, as a child in the 70s I was reading books by Wellman’s brother, Paul Ilsey Wellman. He is best remembered for his historical novels, none of which I have read, but also wrote history books about the Indian wars of the USA. In 1934 and the next year he released Death on the Prairie and Death in the Desert, which, for their time, are extremely good introductions to the (primarily) Sioux and Apache wars, respectively.

Around 1960, Wellman condensed these two books into a single volume for children, Indian War and Warriors West. He also wrote a companion volume, Indian Wars and Warriors East. I devoured these books when I was in 2nd Grade, and a few years later, acquired and read the original grown-up western volumes (I almost typed “adult western,” but that’s a different genre 😉 ). I always lamented there wasn’t a Death in the Forest more substantial version of the East book, but I still got a great basic education in the topic, from it.

Nictzin Dyahlis’ (and is that or is that not the greatest name ever for a fantasy author? And it was actually, legitimately his name!) complete works were collected by DMR Books as The Sapphire Goddess a few years back.

All three Echoes of Valor were great and it’s a shame the series didn’t continue, and that the books are out of print.

Volume II is 1989, not 1991; I know I got the first two tail end of High School, early college, didn’t see III until long after.