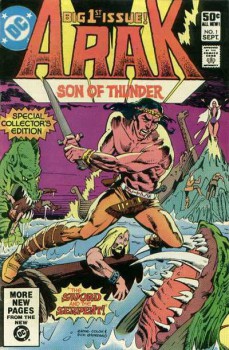

ARAK Issue 1: The Sword and the Serpent!

In the summer of 1981, DC Comics proudly presented “the coming of a great new hero who stalks the fear-haunted shadows of an age of darkness” — Arak, Son of Thunder!

In the summer of 1981, DC Comics proudly presented “the coming of a great new hero who stalks the fear-haunted shadows of an age of darkness” — Arak, Son of Thunder!

Arak was brought to life by Roy Thomas, who’d cut his sword-and-sorcery eyeteeth launching the most successful S&S comic-book franchise ever over at Marvel (the line of Conan titles), and penciler Ernie Colon. It had all the earmarks of such titles — swashbuckling action, magic, monsters, and mayhem — but Arak was not just another generic brute barbarian among the sundry pale imitations of Robert E. Howard’s iconic character. No, Thomas seems to have had bigger ambitions for this epic tale, both in its historical moorings and its complexity.

Thomas uses the back page, the one later reserved for a letters column, to explain what he was up to, in an editorial entitled “A SHORT HISTORY OF THE WORLD, DC-STYLE!”

The editorial begins with the observation “They called them the DARK AGES — but we hope to make them blaze with the light of adventure and heroism.”

What follows that intriguing lead line is a brief history lesson of the “latter half of the first millennium A.D.,” during which this series is set. Of course, Howard himself used a quasi-historical background for his famous barbarian, but the “Hyborian Age” was set so far in the shadowy past that he had a good deal of leeway. By conceiving his story as historical fantasy set in a more recent era, Thomas does create more work for himself, although, granted, there probably weren’t too many medieval historians who would be reading the comic and calling him out (I certainly wouldn’t know if he got some minor detail wrong about the court of the king of the Franks).

Where his leeway lies — and where he really gets to have fun and play — is in the fact that he clearly defines this as alternate history, predicated on this premise: “Ah, but what if there were another earth somewhere — a parallel planet, existing but a heartbeat away from our world yet forever separated from it — an earth on which events and names and geography were much like our own, but with one all-important difference: What if, on that world…MAGIC WORKED?”

I picked up Helen Oyeyemi’s third novel, 2009’s White is for Witching, knowing very little about it. I’d read that Oyeyemi was a highly-regarded young writer in ‘mainstream’ literary circles, whose work contained some speculative elements (born in 1984, her first book had been 2005’s The Icarus Girl, followed by The Opposite House in 2007; a fourth book, Mr Fox, came out in 2011). What I found in White is for Witching was an excellent horror story whose intricacy demanded careful attention. It’s sharply-written and tightly-constructed, and if its plot is not immediately clear, the book’s strong enough to encourage careful attention.

I picked up Helen Oyeyemi’s third novel, 2009’s White is for Witching, knowing very little about it. I’d read that Oyeyemi was a highly-regarded young writer in ‘mainstream’ literary circles, whose work contained some speculative elements (born in 1984, her first book had been 2005’s The Icarus Girl, followed by The Opposite House in 2007; a fourth book, Mr Fox, came out in 2011). What I found in White is for Witching was an excellent horror story whose intricacy demanded careful attention. It’s sharply-written and tightly-constructed, and if its plot is not immediately clear, the book’s strong enough to encourage careful attention.

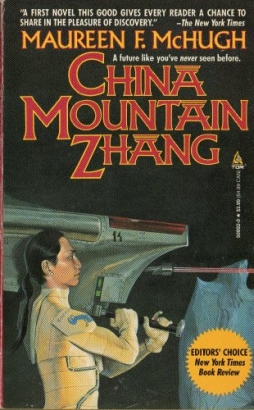

There’s a distinctive kind of surprise some science fiction books can generate: surprise that a book which seems to be speaking to the beliefs, fears, or world-view of a given time was in fact written well beforehand. I remember being taken aback, for example, that A Clockwork Orange was first published in 1962, before hippies and punks and the coining of ‘generation gap’ (first recorded 1967). And it’s interesting to me that Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang, published in 1992, calmly and thoroughly imagines a future dominated by China — something much discussed today, but a less common idea before the turn of the millennium. McHugh’s book is a twentieth century novel, lacking a world wide web or smartphones, that speaks to the twenty-first.

There’s a distinctive kind of surprise some science fiction books can generate: surprise that a book which seems to be speaking to the beliefs, fears, or world-view of a given time was in fact written well beforehand. I remember being taken aback, for example, that A Clockwork Orange was first published in 1962, before hippies and punks and the coining of ‘generation gap’ (first recorded 1967). And it’s interesting to me that Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang, published in 1992, calmly and thoroughly imagines a future dominated by China — something much discussed today, but a less common idea before the turn of the millennium. McHugh’s book is a twentieth century novel, lacking a world wide web or smartphones, that speaks to the twenty-first.