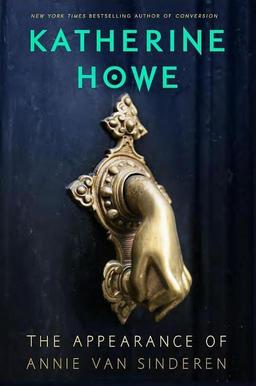

Future Treasures: The Appearance of Annie van Sinderen by Katherine Howe

Katherine Howe’s first novel, The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane, inspired by her family’s connection to the Salem Witch trials, became a New York Times bestseller. Her first YA novel, the bestselling Conversion, was released last year; she was also the editor of The Penguin Book of Witches.

Katherine Howe’s first novel, The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane, inspired by her family’s connection to the Salem Witch trials, became a New York Times bestseller. Her first YA novel, the bestselling Conversion, was released last year; she was also the editor of The Penguin Book of Witches.

Her latest YA novel, The Appearance of Annie van Sinderen, is a haunted love story set in present day New York, the tale of a young filmmaker who falls in love with a ghost who’s been searching to discover exactly what happened to her one dark night in 1825…

It’s July in New York City, and aspiring filmmaker Wes Auckerman has just arrived to start his summer term at NYU. While shooting a séance at a psychic’s in the East Village, he meets a mysterious, intoxicatingly beautiful girl named Annie.

As they start spending time together, Wes finds himself falling for her, drawn to her rose-petal lips and her entrancing glow. There’s just something about her that he can’t put his finger on, something faraway and otherworldly that compels him to fall even deeper. Annie’s from the city, and yet she seems just as out of place as Wes feels. Lost in the chaos of the busy city streets, she’s been searching for something — a missing ring. And now Annie is running out of time and needs Wes’s help. As they search together, Annie and Wes uncover secrets lurking around every corner, secrets that will reveal the truth of Annie’s dark past.

The Appearance of Annie van Sinderen will be published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons on September 15, 2015. It is 384 pages, priced at $18.99 in hardcover and $10.99 for the digital version. The cover is by Theresa M. Evangelista.

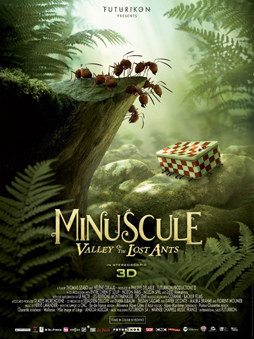

I took a day off from Fantasia on Tuesday, July 28, to run some errands and buy some groceries, then returned on Wednesday to begin a kind of mini-marathon that would carry me through to the end of the festival. I saw four movies Thursday, starting at the De Sève with a wordless 3D animated French film called Minuscule, about a ladybug who falls in with a group of ants who’ve liberated a box of sugar from an abandoned picnic. After that I went to the screening room to see an Australian horror-suspense movie called Observance. Then I went back to the De Sève for the semi-science-fictional German action movie Boy 7. After getting out of that one, I made a snap decision to run across the street to the Hall Theatre to watch the Korean action-comedy Big Match. Which turned out to be one of the better calls I made all festival.

I took a day off from Fantasia on Tuesday, July 28, to run some errands and buy some groceries, then returned on Wednesday to begin a kind of mini-marathon that would carry me through to the end of the festival. I saw four movies Thursday, starting at the De Sève with a wordless 3D animated French film called Minuscule, about a ladybug who falls in with a group of ants who’ve liberated a box of sugar from an abandoned picnic. After that I went to the screening room to see an Australian horror-suspense movie called Observance. Then I went back to the De Sève for the semi-science-fictional German action movie Boy 7. After getting out of that one, I made a snap decision to run across the street to the Hall Theatre to watch the Korean action-comedy Big Match. Which turned out to be one of the better calls I made all festival.

No-one’s a perfect critic, and I’ll readily confess to being less perfect than most. At any rate, sometimes a film’s best appreciated with a certain level of knowledge. Maybe you know too much about the film’s subject, and you see nothing new. Or you know too little, and you find yourself lost. In the latter case, at least, you can wonder whether your lack of knowledge is representative of a general audience, if not of whatever audience the artist has in mind. No critic’s going to be able to hit the sweet spot of knowing just enough, not every time out. Nobody’s perfect.

No-one’s a perfect critic, and I’ll readily confess to being less perfect than most. At any rate, sometimes a film’s best appreciated with a certain level of knowledge. Maybe you know too much about the film’s subject, and you see nothing new. Or you know too little, and you find yourself lost. In the latter case, at least, you can wonder whether your lack of knowledge is representative of a general audience, if not of whatever audience the artist has in mind. No critic’s going to be able to hit the sweet spot of knowing just enough, not every time out. Nobody’s perfect.