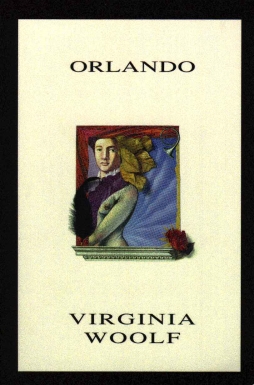

Rereading Orlando

For some years now I’ve been wanting to reread Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I first read the book about twenty years ago, and though I enjoyed it I came away confused. I felt as though on some level I really hadn’t understood the book. As though I hadn’t grasped how to read it. So, time having passed and me having (maybe) come to understand a bit more about books and reading, I sat down with Orlando again. And, as I’d hoped, I enjoyed it more thoroughly this time around, and felt as though I’d understood it a little better than I had. What surprised me was the reason for that understanding. I felt as though I’d worked out how to approach the book not because of any greater knowledge of modernism, or even because I’d read other books by Woolf, but because I now had a greater experience of early fantasy. More than I’d remembered or understood when I first read the book, Orlando is of a piece with the fantastic fiction of its time.

For some years now I’ve been wanting to reread Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I first read the book about twenty years ago, and though I enjoyed it I came away confused. I felt as though on some level I really hadn’t understood the book. As though I hadn’t grasped how to read it. So, time having passed and me having (maybe) come to understand a bit more about books and reading, I sat down with Orlando again. And, as I’d hoped, I enjoyed it more thoroughly this time around, and felt as though I’d understood it a little better than I had. What surprised me was the reason for that understanding. I felt as though I’d worked out how to approach the book not because of any greater knowledge of modernism, or even because I’d read other books by Woolf, but because I now had a greater experience of early fantasy. More than I’d remembered or understood when I first read the book, Orlando is of a piece with the fantastic fiction of its time.

Orlando was first published in 1928. I have the impression that it’s read and spoken of primarily as an artifact of literary modernism, which is fair enough — Woolf was certainly one of the great modernists. But it’s worth remembering that Hope Mirrlees, who wrote the great fantasy Lud-in-the-Mist in 1926, was also a consciously modernist writer. And, to me, having read only To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway among Woolf’s other work, the approach of Orlando is much more like something out of Lord Dunsany than it is similar to Woolf’s technique in those other novels. Orlando avoids inner monologue, presenting itself as written by an obtrusive biographer, playfully claiming to base its text on carefully-scrutinised sources, staying silent where these sources are silent; reading it I think of Joyce Carol Oates’ Gothic Quintet (which boasts an array of odd biographers, as well as at least one pivotal sex-change), but am also reminded of Dunsany’s mock-scripture of The Gods of Pegāna. I will even go so far as to say that in its playful fantasia on the theme of English history, Orlando distantly reminds me of G.K. Chesterton — a writer who Woolf would otherwise appear to be as unlike as it is possible to be.