The Man Who Was Gilbert Keith Chesterton

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges, Alberto Manguel, and Slavoj Žižek. There’s even a movement to canonise Chesterton, a late convert to Catholicism, as a saint. Many of his writings are online, so you can judge him for yourself; you can find a list of texts on this page, a part of this site dedicated to Chesterton.

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges, Alberto Manguel, and Slavoj Žižek. There’s even a movement to canonise Chesterton, a late convert to Catholicism, as a saint. Many of his writings are online, so you can judge him for yourself; you can find a list of texts on this page, a part of this site dedicated to Chesterton.

It’s almost traditional to say that Chesterton’s writing was defined by paradoxes. It’s not entirely accurate, I think. It’s more precise to say that in both his fiction and non-fiction he often put forward propositions structured something like: “It is frequently said that x is the case; but it is not true. In fact the very opposite is true.” From which point Chesterton would then explain, clearly, simply, and with a common-sense air, just how the opposite of everyone’s assumption was the actual state of affairs. In feeble imitation, I might put it this way: it is not true that Chesterton was a writer who delighted in paradoxes. In fact the very opposite is true. He was a writer that delighted in showing that apparent paradoxes were nothing of the sort, and were easily explained by an appeal to reality. We must not forget that Chesterton studied as an artist; and artists, perhaps more than any other sort of person, are concerned with finding the proper perspective on things.

Chesterton certainly writes convincing, clear prose, using simple and direct language with a variety of rhythms. And perhaps because of that artistic training, he excels at creating memorable images. But his view of things is often too simple, and if you don’t share his outlook he may seem frustratingly smug, too sure of his own perception, and simply prejudiced. Among other things, that means the characters of his fictions are flat. But then again, he rarely aimed at psychological realism in any traditional sense: he was a tale-teller, and his tales were outlandish and joyfully unreal. His works read like the essence of parables and fables that have been somehow decanted and rebottled as novels and short stories.

Chesterton certainly writes convincing, clear prose, using simple and direct language with a variety of rhythms. And perhaps because of that artistic training, he excels at creating memorable images. But his view of things is often too simple, and if you don’t share his outlook he may seem frustratingly smug, too sure of his own perception, and simply prejudiced. Among other things, that means the characters of his fictions are flat. But then again, he rarely aimed at psychological realism in any traditional sense: he was a tale-teller, and his tales were outlandish and joyfully unreal. His works read like the essence of parables and fables that have been somehow decanted and rebottled as novels and short stories.

Chesterton’s been called “a genius who wrote no masterpiece” (to use P.J. Kavanagh’s phrase). I wonder if this isn’t the seed for another Chestertonian inversion: you could say that his genius was not of the sort that creates masterpieces. He wrote at speed and in bulk, and was a critic and journalist as much as a novelist or poet. He was involved with his times, with politics and the world around him; if his writing sometimes seems pugnacious, it’s perhaps because he loved to argue. He’s provocative because he intended to provoke.

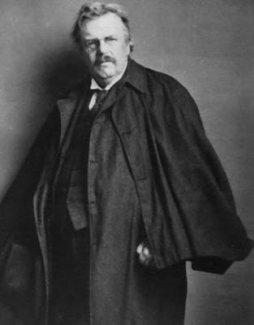

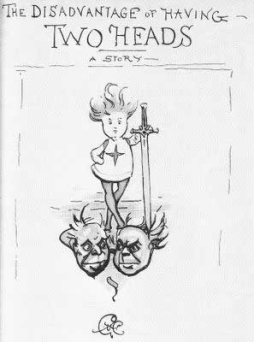

Born in 1874 to middle-class parents who supported him in his interest in art and literature, Chesterton was bookish and absent-minded, intelligent but unwilling to focus on what did not interest him. He went to college to study art, with the aim of becoming a children’s book illustrator (examples of his drawings are at left and at right), but grew more interested in writing himself. He left school in 1895 to work as a publisher’s reader, then moved into journalism. He published his first books, collections of poems, in 1900. Many more followed, almost literally too many to list.

Born in 1874 to middle-class parents who supported him in his interest in art and literature, Chesterton was bookish and absent-minded, intelligent but unwilling to focus on what did not interest him. He went to college to study art, with the aim of becoming a children’s book illustrator (examples of his drawings are at left and at right), but grew more interested in writing himself. He left school in 1895 to work as a publisher’s reader, then moved into journalism. He published his first books, collections of poems, in 1900. Many more followed, almost literally too many to list.

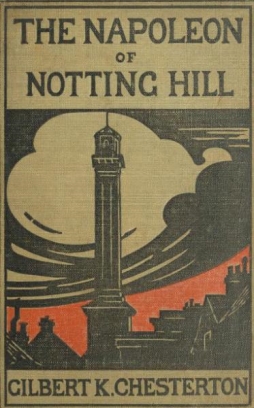

He had fallen in love in 1896 with a woman named Frances Alice Blogg; they married in 1901. Chesterton’s wife encouraged his increasing interest in Christianity, and he became an Anglican soon after his marriage. In 1904 he published his first novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill. He’d write several more over the following years, though his production of novels would slow after the First World War. By that time he’d become famous, an associate of Hilarie Belloc and George Bernard Shaw. A big man, six foot four, he’d grown heavier and heavier into his thirties. Typically clad in a cloak and wide-brimmed hat, carrying a sword-cane and smoking a cigar, he was a distinctive figure.

Overcoming an illness that kept him bedridden for much of 1914, Chesterton remained incredibly prolific all his life, even after taking over as editor of the weekly New Witness paper (later renamed G.K.’s Weekly) from his deceased brother in 1918. In 1922 he formally converted to Catholicism (and also became a believer in the Catholic-inspired economic theory of distributism). In 1936 the overworked Chesterton fell ill again, and died on June 14, 1936.

Overcoming an illness that kept him bedridden for much of 1914, Chesterton remained incredibly prolific all his life, even after taking over as editor of the weekly New Witness paper (later renamed G.K.’s Weekly) from his deceased brother in 1918. In 1922 he formally converted to Catholicism (and also became a believer in the Catholic-inspired economic theory of distributism). In 1936 the overworked Chesterton fell ill again, and died on June 14, 1936.

Most of Chesterton’s novels are nominally fantasies or science-fiction, but more fundamentally they’re surreal in a very specific Chestertonian way. Even the novels and stories not explicitly fantastic have the feel of a world that doesn’t quite operate according to the rules we think we know. As I said above, Chesterton wasn’t interested in realism — at least not as anyone else defined the term.

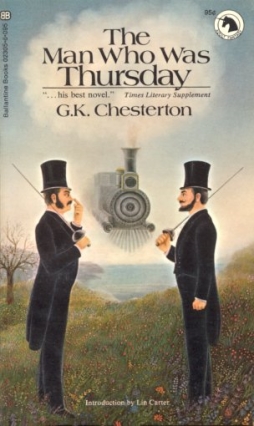

Perhaps his most famous novel, and the one widely accounted to be his best, is The Man Who Was Thursday, first published in 1908. It begins strangely, and grows stranger as it goes on. It has to do with an elite cabal of anarchists, who are infiltrated by an agent of the law. We follow him as he goes about trying to bring the anarchists down — and finds out increasingly surprising facts about all the other members of the cabal, all of whom live in fear of their chief, the mysterious man known only as Sunday. Any resemblance to actual anarchists, living or dead, is quite improbable. These anarchists and their plots are philosophical contrivances, allowing Chesterton to construct a peculiar kind of allegory; these are, almost literally, anarchists of the mind. The book twists and turns and continually does what you wouldn’t expect. It’s wild, and wildly entertaining.

His first novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill, was about a war between neighbourhoods of a future London; with scenes of antiquaries debating the true etymologies of London locations, it inspired Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere (as Gaiman acknowledged by taking a line from the book as an epigraph for his novel). Other novels include The Ball and the Cross, first published as a whole in 1909 after partial serial publication in 1905 and 1906; Manalive, from 1912; 1914’s The Flying Inn; and his final novel, The Return of Don Quixote, in 1927. Given how much else he wrote, that’s not actually very many books, and it is perhaps debateable whether Chesterton’s gifts really lay with the novel.

His first novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill, was about a war between neighbourhoods of a future London; with scenes of antiquaries debating the true etymologies of London locations, it inspired Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere (as Gaiman acknowledged by taking a line from the book as an epigraph for his novel). Other novels include The Ball and the Cross, first published as a whole in 1909 after partial serial publication in 1905 and 1906; Manalive, from 1912; 1914’s The Flying Inn; and his final novel, The Return of Don Quixote, in 1927. Given how much else he wrote, that’s not actually very many books, and it is perhaps debateable whether Chesterton’s gifts really lay with the novel.

Chesterton also produced several collections of mystery tales, including sixty stories featuring his best-known hero, Father Brown. A humble English clergyman who constantly sees through the confusion of the world to work out what’s really happening in seemingly-mysterious circumstances, Brown and his stories are examples of how Chesterton’s inversions of common sense work: Brown, seemingly a quiet and colourless man, makes a good sleuth because as a priest he’s constantly exposed to the unvarnished truth of human nature and human brutality. In general, in the Brown stories and beyond, Chesterton’s interest in mysteries follows from his ability to see things in a different light: he didn’t write puzzles, but optical illusions in prose. Father Brown sees things more clearly than anyone; and in a sense, perhaps, that’s what Chesterton does in these stories — help his readers see more clearly. At least by his lights.

It’s been said that Chesterton was at heart an essayist, and his stories are really disguised essays. There’s some truth to that, though it overlooks his pure narrative gifts. It is true that Chesterton was a talented critic. His volume on Charles Dickens has been praised by readers from T.S. Eliot to Peter Ackroyd. But his tendency to pontificate doesn’t always serve his fiction, especially when his statements are based on verbal inversions and strained logic. And especially to a reader whose perceptions are at odd with his own.

Chesterton was a man of his era, so it’s not surprising to see him occasionally using racial epithets that would be unacceptable today. Nor is it surprising that he partook (however distinctively) of his era’s attitudes to gender. Chesterton’s been charged with Anti-Semitism, and if he still has fierce defenders today, I can only say that he wrote things I personally would not care to defend. It is probable that his views changed over the course of his life; certainly he opposed Nazism relatively early. I think that the way Chesterton thought, reducing things to what he perceived as their essence, was a problem for him in this. You find passages like the one in Manalive where a Jewish character “laughed at the thing with the shameless rationality of another race.” There’s an awareness of otherness, an excessive sense of foreignness, of the strangeness of people, any people, who did not act like the people he had identified as his own.

Chesterton was a man of his era, so it’s not surprising to see him occasionally using racial epithets that would be unacceptable today. Nor is it surprising that he partook (however distinctively) of his era’s attitudes to gender. Chesterton’s been charged with Anti-Semitism, and if he still has fierce defenders today, I can only say that he wrote things I personally would not care to defend. It is probable that his views changed over the course of his life; certainly he opposed Nazism relatively early. I think that the way Chesterton thought, reducing things to what he perceived as their essence, was a problem for him in this. You find passages like the one in Manalive where a Jewish character “laughed at the thing with the shameless rationality of another race.” There’s an awareness of otherness, an excessive sense of foreignness, of the strangeness of people, any people, who did not act like the people he had identified as his own.

It’s a part of the overall exasperating aspect of Chesterton: there’s something in him to annoy almost anyone. Chesterton was in some ways instinctively conservative, though in other ways instinctively radical, and so was skeptical of any attitude that presented itself as progressive — or modern, or rational. Sometimes he was quite right, as when he opposed eugenics. At other times one has the engaging experience of watching a man with a keen sense of rhetoric valiantly and even idealistically attempting to defend the indefensible.

For better or worse, Chesterton was always an inventive writer. In his non-fiction that meant he tended to rely on abstractions (like, say, ‘the poor’ and ‘the rich’ and ‘educated people’) about which he would weave his surprising prose inventions. Perhaps the statement I noted above, that Chesterton’s stories seem to want to be essays, is again susceptible to reversal: Chesterton’s essays all want to be stories, living through anecdote and imagery more than connected argument or deep scholarship. At any rate, it seems to me that Chesterton’s fictions are worth reading to the extent that they’re continually inventive. When, as in Thursday, that creativity was present throughout, he created something remarkable. When it flags, the tales become correspondingly less inventive; his plotting and characterisation were rarely strong points. But his books are always technically well written, and contain strong imagery. Consider the opening paragraph of Manalive:

A wind sprang high in the west, like a wave of unreasonable happiness, and tore eastward across England, trailing with it the frosty scent of forests and the cold intoxication of the sea. In a million holes and corners it refreshed a man like a flagon, and astonished him like a blow. In the inmost chambers of intricate and embowered houses it woke like a domestic explosion, littering the floor with some professor’s papers till they seemed as precious as fugitive, or blowing out the candle by which a boy read “Treasure Island” and wrapping him in roaring dark. But everywhere it bore drama into undramatic lives, and carried the trump of crisis across the world. Many a harassed mother in a mean backyard had looked at five dwarfish shirts on the clothes-line as at some small, sick tragedy; it was as if she had hanged her five children. The wind came, and they were full and kicking as if five fat imps had sprung into them; and far down in her oppressed subconscious she half-remembered those coarse comedies of her fathers when the elves still dwelt in the homes of men. Many an unnoticed girl in a dank walled garden had tossed herself into the hammock with the same intolerant gesture with which she might have tossed herself into the Thames; and that wind rent the waving wall of woods and lifted the hammock like a balloon, and showed her shapes of quaint clouds far beyond, and pictures of bright villages far below, as if she rode heaven in a fairy boat. Many a dusty clerk or cleric, plodding a telescopic road of poplars, thought for the hundredth time that they were like the plumes of a hearse; when this invisible energy caught and swung and clashed them round his head like a wreath or salutation of seraphic wings. There was in it something more inspired and authoritative even than the old wind of the proverb; for this was the good wind that blows nobody harm.

The line about “refreshed a man like a flagon, and astonished him like a blow” captures something of the vigor and combativeness of Chesterton; the professor with scattered papers reflects his gentle mockery of academia. The implied levelling of the professor and the boy reading Stevenson is an example of the way he calls values into question: Chesterton always championed Romance, and so it is here. The way the wind breathes life into children’s shirts hanging on a clothes-line seems also to reflect his ability to see and describe the world as animated in strange ways; his power to show how any given thing can at any moment, when we don’t expect it, turn out to be something else entirely.

It may be fair to say, and it might even have amused Chesterton to hear, that he was for both good and bad essentially childish. Bad, because he viewed the world essentially simplistically, denying the complexity of large groups of people and even of individual characters. Good, because he was able to see the world as a child does, and so describe it: without the preconceptions adults develop. The upside-down world he gives us, the surreal place with rules we come to see that we don’t understand, is the world a child knows. It is a world approached with the sense that things really are simple, and just as they appear.

It may be fair to say, and it might even have amused Chesterton to hear, that he was for both good and bad essentially childish. Bad, because he viewed the world essentially simplistically, denying the complexity of large groups of people and even of individual characters. Good, because he was able to see the world as a child does, and so describe it: without the preconceptions adults develop. The upside-down world he gives us, the surreal place with rules we come to see that we don’t understand, is the world a child knows. It is a world approached with the sense that things really are simple, and just as they appear.

To say he describes a world upside-down may also say something important. Chesterton’s got a touch of the spirit of Twelfth-night, I think, the holiday at the end of the Twelve Days of Christmas traditionally marked by the exuberant overturning of all authority and inversion of all hierarchy — which inversion, one might argue, is a sign of the power of those hierarchies. Chesterton’s flamboyant, often-exasperating personality is that of a Lord of Misrule. There is something of the carnivalesque, if not the festive, in his writing (as well as in his Christianity). And there is a sense in which the end of The Man Who Was Thursday is a holy feast, a Last Supper that is also a First Supper, and yet also a feast of fools. That sense of joy is not always accessible to everyone, and perhaps not always communicated well. But to the extent it can be seen to live in his work, to that extent the work lives as well.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Great post! I’ve never read any of Chesterton’s fiction. I’m only familiar with his book Orthodoxy, and I only mainly read that because I was told it was incredibly influential upon C. S. Lewis.

I’ve seen quite a bit of renewed interest in Chesterton in the past few years. I think there is something of a resurgence concerning Chesterton right now. I hope his fiction gets a renewed bump as well.

Thanks, James! I think you may be right about increasing interest in Chesterton. I do suspect having people like Gaiman citing his work really encourages people to read him. I wonder if it might help that most of his work is out of copyright, and available for free?

My favorite thing about Chesterton is the humor and wit in his criticisms. He understood there really is magic and wonder in the universe and it wasn’t to be found in the dreary obsessions of modernity. Sometimes his wit comes across as smug but only in the same way that an experienced, intelligent adult can appear smug to a college sophomore who thinks he/she has all the answers after listening to a couple lectures and reading a bit of Foucault. That those who embrace the current zeitgeist find fault with him is a complement and not a condemnation.

A Merry Christmas to everyone and thanks for another year of interesting columns and fiction.

Although I’ve read and enjoyed ‘The Man Who Was Thursday’ and ‘The Napoleon of Nottinghill’, I reckon they show Chesterton at his most whimsical. I prefer the Father Brown stories as they dig a bit deeper, psychologically speaking. You describe them as ‘optical illusions’: I’ve always thought of each story as a perfectly executed conjuring trick (complete with selective lighting and misdirection) that catches the reader out each and every time. Great minds, eh?

[…] The Man Who Was Gilbert Keith Chesterton […]