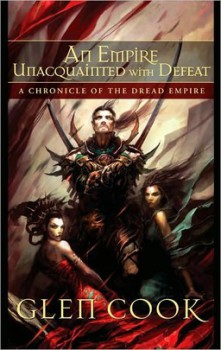

An Empire Unacquainted with Defeat by Glen Cook

Glen Cook is the author of some of my hands-down favorite books. I hold out his Black Company series as arguably the best military fantasy ever written. The early Garrett books set a standard for the blending of fantasy and hardboiled fiction. But what introduced me to Cook and made me a fan for life was his earlier work, the Dread Empire series, starting with the short story “Filed Teeth.”

Glen Cook is the author of some of my hands-down favorite books. I hold out his Black Company series as arguably the best military fantasy ever written. The early Garrett books set a standard for the blending of fantasy and hardboiled fiction. But what introduced me to Cook and made me a fan for life was his earlier work, the Dread Empire series, starting with the short story “Filed Teeth.”

The first time I ever saw the name Glen Cook was on the first three Dread Empire books, bound together with a rubber band on the bottom shelf in my local used book store. I didn’t like the cover illustrations (I still don’t) and I thought the whole “Dread Empire” thing seemed a little too dopey.

Then my dad tossed me Orson Scott Card’s Dragons of Darkness anthology. The first story in it, “Filed Teeth,” was set in the aftermath of a great war involving the Dread Empire and it blew me away! I had to have those books I had casually dismissed only a few weeks before.

The next day I took the bus to the book store and bought all three. I devoured them. They’re not as polished as many of his later books, but there are episodes of genius that range from vast fantastic battles to tender moments of pathos. The series introduces us to Cook’s likable trio of rogues, Bragi Ragnarson, Mocker and Haroun bin Yousif. The books begin with the trio scheming to make themselves wealthy beyond compare, and culminates in a war between huge armies and unbelievably powerful sorcery. If you like his other books, I highly recommend them.

Since then I’ve bought most of Cook’s books as soon as they hit the shelves. The six years I had to wait between the sixth and seventh Black Company books were among the worst I’ve encountered as a reader. The news that a new Black Company book is in the wings has me twitching.