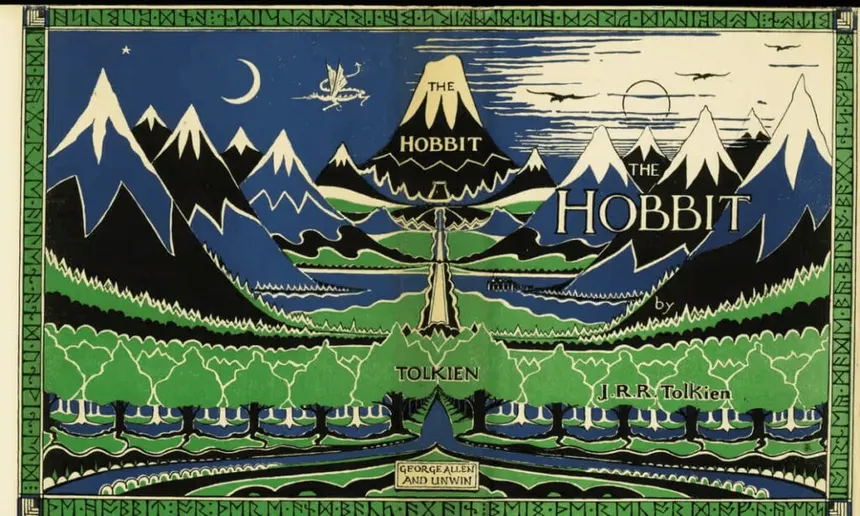

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Five: From the Beginning — The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

Chapter 1, An Unexpected Party – The Hobbit

Fifty years ago, when I first read this book, I didn’t imagine I’d still be reading it so many years later. Heck, I doubt I could have even imagined being as old as I am now. But I do reread it every few years. When I revisit The Hobbit, my journey is bathed in nostalgia as much as with the simple enjoyment caused by reading a charming book that I happen to know inside out, from the opening line above on through to the very end.

In my initial article on half a century of reading Tolkien back in January, I described my dad trying to get our first color tv in time to watch the Rankin & Bass The Hobbit. Remembering that again last week left me thinking more of my dad, now gone nearly 24 years, than the book. He was ten years younger than I am now when the movie first aired, which makes me feel incredibly old at the moment. For such a conservative man, he was excited to see it — admittedly, in a restrained way. I think we liked it well enough, but leaving out Beorn irked us both. Beyond Tolkien’s books, our fantasy tastes rarely coincided (I’ve got a shelf full of David Eddings books he bought, if anyone’s interested), but with The Hobbit and LOTR, we were in complete agreement.

What’s there to say about The Hobbit here on Black Gate? Nothing, really. I imagine most visitors here have read it, many more than once, and have their own ideas on it. It’s one of the most widely read books in the world. Instead, I’m going to discuss some adaptations of the book. But first, a summary.

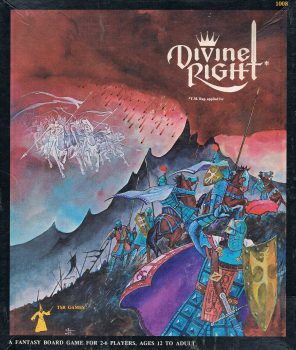

In the summer of 1981, my friend Alex R. had moved into a big, new house not far from the Staten Island neighborhood where most of my other friends lived. As his parents were rarely home and summer was beginning, we spent all our days and most nights there, watching movies and playing D&D. Things changed significantly when George K. showed up one day with a copy of TSR’s fantasy wargame,

In the summer of 1981, my friend Alex R. had moved into a big, new house not far from the Staten Island neighborhood where most of my other friends lived. As his parents were rarely home and summer was beginning, we spent all our days and most nights there, watching movies and playing D&D. Things changed significantly when George K. showed up one day with a copy of TSR’s fantasy wargame,

One of the

One of the