Such Stuff As Dreams Are Made On: The Tempest by William Shakespeare

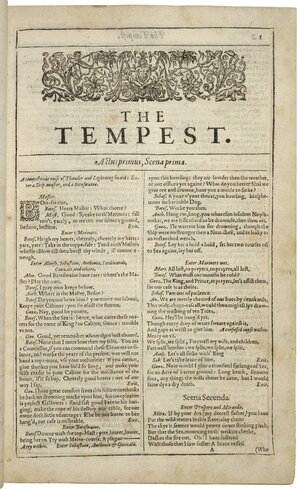

One of the problems with writing about great works is there’s so little for me to add to the volumes and volumes written by writers far and away more knowledgable than I. Still, maybe I can bring a newcomer’s eye to books that have nourished the roots of fantasy, and maybe encourage a few others to pick them up. So I shall ramble for a piece about William Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest (ca. 1610).

The Tempest is believed to have been performed only a few times during Shakespeare’s lifetime, including once in 1611 for King James I at Whitehall Palace on Hallowmas night. It became part of the standard theatrical repertoire during the Restoration starting in 1660, but was edited to appeal more to upper-class audiences and support royalist policies. Finally, in 1838, when actor William Charles Macready staged an incredibly elaborate production using the unedited script, Shakespeare’s original became the preferred version.

Along with several other of Shakespeare’s final plays, including The Winter’s Tale and Cymbeline, The Tempest is categorized as a romance, fitting into none of the standard tragedy, comedy, or history categories. His later works, perhaps reflecting his own changing nature, changing tastes, and the growth of more elaborate productions, mix the comic and tragic, along with magic and mystical elements. The Tempest showcases this evolution brilliantly.

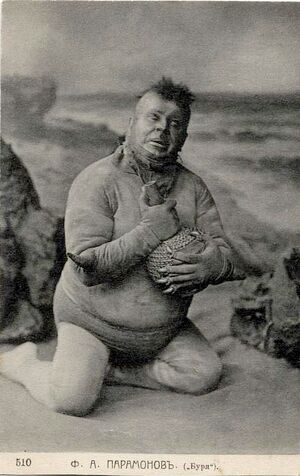

Prospero had been Duke of Milan, but his attention was turned toward philosophical and thaumaturgical studies. His dastardly brother, Antonio, aided by Alonso, King of Naples, usurped his throne and set him adrift at sea with his young daughter Miranda. For twelve years he has lived on a small island with Miranda, Caliban, a monstrous demi-human, and Ariel, a conjured spirit.

Prospero tried to civilize Caliban, the son of Sycorax, a long-dead witch, and a demon. Caliban showed his gratitude by attempting to rape Miranda, so Prospero enslaved him instead.

Caliban: You taught me language, and my profit on’t

Is, I know how to curse. The red plague rid you,

For learning me your language!

Ariel was discovered imprisoned within a tree, cursed by Sycorax. Prospero freed the spirit from fourteen years of confinement but bound him to his service.

One fortuitous day, a ship carrying Antonio, Alonso, and several other people including Alonso’s son and brother, passes by the island. Inspired to regain his throne and avenge himself on those who wronged him, Prospero sends Ariel forth to raise up a tempest to strand the ship and its passengers on his island. What follows is a mix of sublime magical sequences, some buffoonish comedy, and passages of great beauty.

Prospero’s scheme is centered around his daughter Miranda and Alonso’s son Ferdinand falling in love, marrying, and providing his own descendants to sit on the throne of Naples. He promises to free Ariel if his plan goes right.

The Tempest opens with a ship tossed and wracked by the storm of the title, its crew straining to keep it from running aground and its passengers panicking. Just as it seems about to go down, the scene switches to Prospero’s chambers. Miranda is terrified that the poor people on the ship will drown and, convinced her father is responsible for the storm, begs him to save them.

After assuring her they are safe from real harm, he decides to fill her in on much of his plot. Through lengthy conversation with Miranda and Ariel, the audience learns his history, the nature of his two servants, and his plans.

Prospero: ’Tis time

I should inform thee farther. Lend thy hand,

And pluck my magic garment from me.—So:[Lays down his mantle.]

Lie there my art. Wipe thou thine eyes; have comfort.

The direful spectacle of the wrack, which touch’d

The very virtue of compassion in thee,

I have with such provision in mine art

So safely ordered that there is no soul—

No, not so much perdition as an hair

Betid to any creature in the vessel

Which thou heard’st cry, which thou saw’st sink. Sit down;

For thou must now know farther.

The characters are broken into several separate groups for most of the play. The first is Miranda and Ferdinand, falling in love and that love being tested and tempered by Prospero. To prove his love, the prince gladly undertakes the heavy tasks set him by the wizard.

The second consists of Caliban, Alonso’s butler, Stephano, and his jester, Trinculo. Alonso’s two servants are drunk and give wine to Caliban. The monster, believing the wine has miraculous properties, is convinced the butler is a god and offers to worship him. He also persuades him to kill Prospero, marry Miranda, and rule the island himself. This plot is derailed by Ariel who, invisible to the drunkards, sets them against one another.

Stephano: How now shall this be compassed? Canst thou bring me to the party?

Caliban: Yea, yea, my lord: I’ll yield him thee asleep,

Where thou mayst knock a nail into his head.Ariel: Thou liest. Thou canst not.

Caliban: What a pied ninny’s this! Thou scurvy patch!

I do beseech thy greatness, give him blows,

And take his bottle from him: when that’s gone

He shall drink nought but brine; for I’ll not show him

Where the quick freshes are.Stephano: Trinculo, run into no further danger: interrupt the monster one word further, and by this hand, I’ll turn my mercy out o’ doors, and make a stock-fish of thee.

Trinculo: Why, what did I? I did nothing. I’ll go farther off.

Stephano: Didst thou not say he lied?

Ariel: Thou liest.

Stephano: Do I so? Take thou that.

[Strikes Trinculo.]

As you like this, give me the lie another time.

Trinculo: I did not give the lie. Out o’ your wits and hearing too? A pox o’ your bottle! this can sack and drinking do. A murrain on your monster, and the devil take your fingers!

Caliban: Ha, ha, ha!

Finally, Alonso, his brother Sebastian, Antonio, and several councillors wander the island, mostly being harassed by Ariel and rebuked for their past crimes.

Thunder and lightning. Enter Ariel like a Harpy; claps his wings upon the table; and, with a quaint device, the banquet vanishes.

Ariel: You are three men of sin, whom Destiny,

That hath to instrument this lower world

And what is in’t,—the never-surfeited sea

Hath caused to belch up you; and on this island

Where man doth not inhabit; you ’mongst men

Being most unfit to live. I have made you mad;

And even with such-like valour men hang and drown

Their proper selves.

Eventually, all these individuals come together, order is restored, and the future secured.

Bloomsbury Set member Lytton Strachey suggested The Tempest provides insights into Shakespeare as a man and artist.

Is it not thus, then, that we should imagine him in the last years of his life? Half enchanted by visions of beauty and loveliness, and half bored to death; on the one side inspired by a soaring fancy to the singing of ethereal songs, and on the other urged by a general disgust to burst occasionally through his torpor into bitter and violent speech? If we are to learn anything of his mind from his last works, it is surely this.

Strachey, from Books and Characters

From that perspective, it’s easy to imagine Prospero as the playwright’s stand-in. Everything that transpires is at his direction, from the initial storm, to the pageants of spirits that hound the trio of clowns and the noblemen, to the lecture on chastity and marriage delivered by goddesses to the young lovers. His words chide Caliban and, through Ariel, terrifiy Antonio. Prospero is the master of all events in the play, just as Shakespeare is the author of the play itself.

If one were to take the correlation between Prospero and Shakespeare further, something might be seen in the magician’s promise to discard his occult trappings once his objectives are achieved:

graves at my command

Have wak’d their sleepers, op’d, and let ’em forth

By my so potent art. But this rough magic

I here abjure; and, when I have requir’d

Some heavenly music,—which even now I do,—

To work mine end upon their senses that

This airy charm is for, I’ll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I’ll drown my book.

Perhaps, knowing this would the last play he wrote solo as well as the culmination of the sort of plays he’d been writing, it’s Shakespeare speaking this thought aloud through his characters. The time has finally come to lay down the tools of his trade and step back from the stage. A certain melancholy holds over the play, an understanding that for all its majesty is only illusion and must give way to mortality in the end. At one point, Prospero intimates as much while speaking to Ferdinand.

Prospero: You do look, my son, in a mov’d sort,

As if you were dismay’d: be cheerful, sir:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

Prospero’s final speech breaks out of the play’s confines and is directed straight at the audience. He to be set free from the stage – as any playwright would as well — by its applause.

Prospero: Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have’s mine own,

Which is most faint. Now ’tis true,

I must be here confin’d by you,

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got,

And pardon’d the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell,

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands.

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant;

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be reliev’d by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardon’d be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

In his book Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human the late critic Harold Bloom argued that Shakespeare did more than any other author or thinker to change how humans thought about themselves. Not only did he portray us in our multivarious ways better and with more depth than anyone else, but he also was the first person to think about humans with true psychological insight and depth. I suspect Bloom oversold his thesis, but there’s no arguing that few dramatists have created such a wide-ranging and diverse cast of characters. Both the wise and protective Prospero and the vile, though perhaps deeply wronged, Caliban are far more than just mouthpieces for some well-placed words. They have recognizable, human aspects that ring true and memorably.

It’s been a very long time since I’ve read Shakespeare and that’s a shame. I think most of us only encounter his plays in school, which is also a shame. His plays are exciting, moving, and funny, often, as in The Tempest, all in the same play. Yes, these are plays and are written to be performed, but reading them allows you to savor his words in all their beauty and glory at your leisure. There are still so many of his plays I haven’t read or seen yet, and the ones I have, seem to be singing for a revisit.

I would like to see The Tempest on stage. It is a magnificent pageant of words, songs, and magic. I can only imagine how Shakespeare’s words sound from the likes of Sir Michael Hordern or Sir John Gielgud. In fact, here’s Gielgud giving Prospero’s final speech.

If one is worried about difficulty with his language — and it can be difficult at times, simply because of long-disused words and ancient references — I strongly recommend one pick up an annotated edition. His most prominent plays are available in Norton Critical Editions which are amply foot-noted and accompanied by extensive background and critical essays.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

The Best Tempest that I’ve found on film is a 2011 recording of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival’s production with Christopher Plummer, magnificent as Prospero. There’s also an ancient, almost unwatchable (because of video quality) television version with hammy old Maurice “Dr. Zaius” Evans as Prospero, with Richard Burton as Caliban and Roddy McDowall as Ariel.

I loathe the very idea of relevance (if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s a Shakespeare director who thinks I’m too stupid to draw my own inferences), but pertinence to the permanent human things is another matter. The product of a man finishing his life’s work, on the verge of stepping back into the shadows, the Tempest speaks of the necessity of reconciliation, of the wisdom of living in the world as it is and not as we would imagine it to be, and of setting aside the arrogance of shaping and being content with being shaped.

Not exactly ripped from today’s headlines, but pertinent to the way we must live in this soiled world, certainly.

Your description of The Tempest is beautiful. Part of Shakespeare’s brilliance is his ability that he speaks to all humanity. I discovered the Evans last night and posted it to FB. McDowall is so much fun

Not to be a shill for Easton Press, but . . . it might please you to know that they are currently offering a $400 (too rich for my poverty-stricken blood!) version of the magnificent 1908 version which includes 40 full-color illustrations by Edmund Dulac. https://www.eastonpress.com/deluxe-editions/william-shakespeares-the-tempest-2863.html Seems THE TEMPEST is having a moment . . .

Thank you for a great article, Mr. Vredenburgh. I forget when I last enjoyed this play but your work and Mr. Parker’s commentary remind me that it has been too long.

* Any author who plans on writing dialogue in English should at least listen to some of Shakespeare’s plays and The Tempest is a prime candidate. The Bard did indeed speak to all humanity and we can learn a lot from his plays.

Thank you! I’ve been meaning to brush up on my Shakespeare for a while and this has inspired me to get going.

Thank you for this insightful and lovely treatment of one of Shakespeare’s most entertaining plays. Like you, it’s been a while since I’ve read Shakespeare, but I can say that his works are so perceptive and eloquent that they speak more as you mature and have experienced enough of life to appreciate his vision.

Thank you!

I’ve had people tell me the basic plot of most Shakespeare plays, but never ‘The Tempest’ which seems to defy casual summary – so fair dues to you for finally providing me with a synopsis! (which was excellent, btw). My suspicion is that you’re absolutely right re Prospero as a stand-in for Shakespeare himself, and given how both Caliban and Arial are extensions of Prospero, I guess they might be another example of how an author plays around with his characters?

I don’t know if you’ve heard of Neural Love? Basically it’s a piece of software that produces photographic images of characters based on source material like the painting you posted of Shakespeare –

https://twitter.com/codexeditor/status/1409705871936933892/photo/1

I had a bit of fun with it (you just sign on, then upload) – e.g. I got it to convert a few Frazettas, plus a Paget drawing of Holmes. As far as I can tell, it processes faces only, preferably a straightforward pose or three-quarters pose (profiles, not so much).

Thank you. It’s an absolutely wild play and it seems like a good production is something to see. That Shakespeare image is very cool. Thanks for the link

A great review and an enjoyable read. I thoroughly enjoy teaching The Tempest to my grade 10 students, partly because it’s one of my favourite plays, but mostly because it gives me an excuse to show them Forbidden Planet.

Thanks! Now I need to rewatch FB

On my last trip to London, I had the pleasure of attending opening night of the Tempest at the Barbican Centre, performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company. When we arrived, we noticed they had signs up declaring “Intel Inside.” The actor playing Ariel was wearing a motion capture suit and while we watched him acting on stage, we could also see him transform into a bird, etc. on screens placed around the stage. In addition, the stagecraft was incredible and they did some transformations on stage that we weren’t quite able to figure out.

That sounds amazing.

I saw the same production as Steven H Silver, with the magnificent Simon Russell Beale as Prospero. Beale played Mr Lyle in Penny Dreadful and Beria in Death of Stalin, but is best known in the UK as one of the best stage actors of his generation and a great Shakespearean actor.

I’ll never forget him roaring in rage into Ariel’s face when the spirit points out how cruel he has become in seeking revenge.

I need to find out if there’s a recording of the production. Doing a little research, I discovered Beale played Ariel in an earlier production.

This is the production Steve and I saw…http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ISBN=B0735RG7H6/stevensilvershomA/

thank you