Birthday Reviews: Ian R. MacLeod’s “Starship Day”

Ian R. MacLeod was born on August 6, 1956.

MacLeod’s novella Song of Time won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Arthur C. Clarke Award in 2009. His novella “The Summer Isles” won the World Fantasy Award and the Sidewise Award in 1999 and the novel length version also won the Sidewise Award in 2006. He won a third Sidewise Award for Wake Up and Dream in 2012 and a second World Fantasy Award for “The Chop Girl.” He has collaborated with Martin Sketchley on one story.

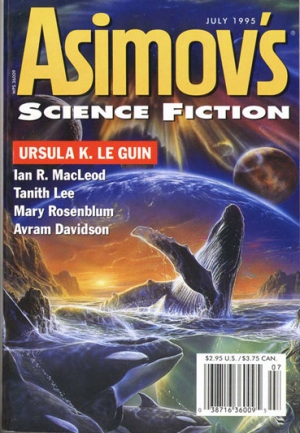

“Starship Day” first appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction in the July 1995 issue, edited by Gardner Dozois. The following year, it was translated for the German edition of the magazine and also appeared in MacLeod’s collection Voyages by Starlight and was selected by Dozois for his The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Thirteenth Annual Collection. In 1997, it was translated into French for inclusion in Cyberdreams 11: Illusions technologiques, edited by Sylvie Denis. John Joseph Adams most recently reprinted the story in the February 2017 issue of Lightspeed.

Stories about generation ships or interstellar voyages usually focus on those who are traveling on the ships. If they deal with the people left behind, it is generally as an afterthought. In MacLeod’s “Starship Day,” people living on a ravaged Earth a generation after a starship left are waiting to hear what the voyagers will find when the finally come out of cryosleep in orbit around a distant planet. In the village of Danous, everyone is sitting on pins and needles waiting to see the transmission with the exception of Owen, the village doctor, who is adamant that it is just another day.

Owen goes out of his way to make the day normal, seeing patients in the morning, having lunch with the latest in a long line of mistresses, who uses the opportunity to break up with him, going home to listen to his wife play her cello before the two go to a viewing party, where Owen considers starting an affair with his wife’s sister, and eventually going to check up on Sal Mohammed, a friend and patient he had seen that morning who failed to attend the party.

When Owen discovers that Sal has committed suicide, possibly in part because of Owen’s own dismissive attitude during their morning appointment, the situation begins to unravel. The message comes in from the starship that there is no planet for them to land on. While everyone else seems to take this in stride, it brings up a variety of emotions for Owen regarding his own lost daughter.

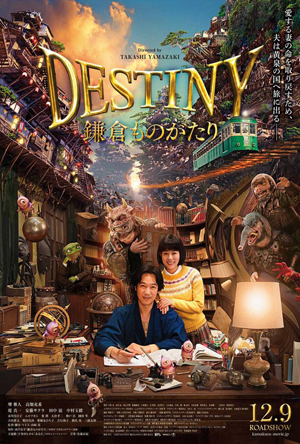

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.