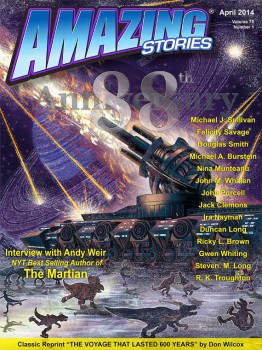

Amazing Stories Turns 88 and Celebrates with a Special Issue

Amazing Stories is one of those legendary magazines of the first fandom age. Launched in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback (ie: the guy the Hugo Awards are named after), it was the first magazine devoted to science fiction stories.

Amazing Stories is one of those legendary magazines of the first fandom age. Launched in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback (ie: the guy the Hugo Awards are named after), it was the first magazine devoted to science fiction stories.

This forerunner status didn’t assure it success and the magazine suffered bankruptcy, changes in ownership, editorial style, legal troubles, and so it has had many incarnations.

In recent years, Steve Davidson and a small army have been making efforts to resurrect Amazing Stories as an e-magazine, at first as a magazine focusing on fandom, and now, more consciously approaching the role of a magazine that will be offering new fiction and a new editorial voice. But, as Davidson notes, baby steps is the key.

The 88th Anniversary issue features articles of science fact, articles about fandom, reprinted short fiction, and some new stories as well. It is a visually-powerful magazine, with some great interior and cover art, so it was beautiful to toggle through on my Kindle.

On the content side, I have strong feelings about the sf field and this magazine pulled those feelings in a couple of directions.

I’ll admit I floundered a bit trying to discern the editorial taste, until I looked at the first fandom context of Amazing Stories and the aura of nostalgia around the age and history of science fiction as a genre.

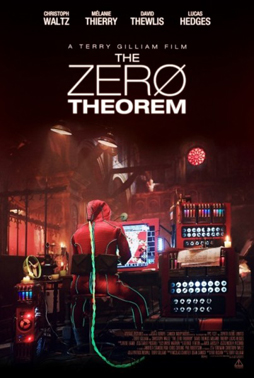

Before continuing my Fantasia diary with a look at the movies I saw last Sunday, I want to focus in on one specific film that struck me as an utterly brilliant piece of science-fiction satire. I think it divided the audience; I’ve heard and seen reactions from people who were left cold by it as well as from people who loved it as much as I did. Perhaps that’s not surprising. The movie is The Zero Theorem, directed by Terry Gilliam from a script by Pat Rushin, and it is as idiosyncratic and persistently individual as you’d expect from Gilliam.

Before continuing my Fantasia diary with a look at the movies I saw last Sunday, I want to focus in on one specific film that struck me as an utterly brilliant piece of science-fiction satire. I think it divided the audience; I’ve heard and seen reactions from people who were left cold by it as well as from people who loved it as much as I did. Perhaps that’s not surprising. The movie is The Zero Theorem, directed by Terry Gilliam from a script by Pat Rushin, and it is as idiosyncratic and persistently individual as you’d expect from Gilliam.

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.