The Problem with Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman is my wife’s favorite superhero, and for good reason. The character is powerful, dynamic, and she isn’t afraid to throw down with evil villains. While I didn’t read the comic, I’m old enough to remember the television series with Linda Carter. I also knew the character from The Super Friends Saturday morning cartoon back in the day.

Wonder Woman is my wife’s favorite superhero, and for good reason. The character is powerful, dynamic, and she isn’t afraid to throw down with evil villains. While I didn’t read the comic, I’m old enough to remember the television series with Linda Carter. I also knew the character from The Super Friends Saturday morning cartoon back in the day.

Every few years, rumors emerge from Hollywood about a Wonder Woman movie or show in the works. We hear about the possible casting choices, and then it goes away for a while. Meanwhile, movies about male superheroes are being churned out as fast as possible.

Recently it was leaked that actress/model Gal Gadot (left) might be cast as the legendary Amazon princess in the next Superman movie, and the internet went ape-poop.

At first I didn’t understand why. Then I read the various comments floating around, most of which had to do with Ms. Gadot being too skinny for the role. Which, of course, started debates about how much muscle mass she could pack on with the right trainer, comparisons to Hugh Jackson, et cetera and so forth.

At first, I thought to myself that it doesn’t matter who they cast; just making the @%#^$* movie. After all the travails this comic juggernaut franchise has encountered on its trek through Hollywood, I just want to see the ball rolling. Heck, it couldn’t be any worse than Daredevil or Green Lantern, right?

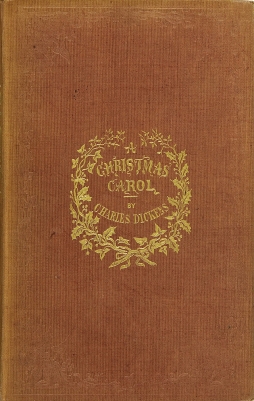

It’s one of the most famous stories in the English-speaking world, and it is a fantasy. A Gothic fantasy of Christmas, and the meaning thereof: the story of the miser and the three spirits. It’s been retold any number of times, parodied, set in America, updated to the modern day, acted out with mice and ducks, with frogs and pigs. It’s easy to overlook how powerful the original work really is.

It’s one of the most famous stories in the English-speaking world, and it is a fantasy. A Gothic fantasy of Christmas, and the meaning thereof: the story of the miser and the three spirits. It’s been retold any number of times, parodied, set in America, updated to the modern day, acted out with mice and ducks, with frogs and pigs. It’s easy to overlook how powerful the original work really is.

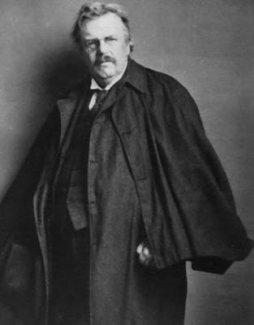

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges,

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges,