Fantasia 2019, Day 20, Part 2: Garo — Under the Moonbow

I approached my second and last film of July 30 with real uncertainty. I’d never seen many tokusatsu films or TV shows, and what I had seen I hadn’t cared for. (‘Tokusatsu’ literally means something like ‘special effects,’ but in the West it’s come especially to refer to shows like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider.) Still, playing in the De Sève Cinema was Garo — Under the Moonbow (Garo: gekkô no tabibito, 牙狼 — 月虹ノ旅人, also translated Garo: Moonbow Traveler), written and directed by Keita Amemiya. It’s the latest installment of a franchise, created by Amemiya, which began with a 2005 TV series and has continued through more TV shows, live-action movies, and anime series. as well as video games, manga, and various other tie-ins. A veteran creator of tokusatsu dramas, Amemiya is particularly known for his powerful design sense, and the images and description of the film promised a stylish fantasy adventure. Although it’d be my first experience with a series that had dozens of hours of continuity behind it, I decided it was worth passing up a chance to see The Crow on the big screen in order to watch Under the Moonbow.

I approached my second and last film of July 30 with real uncertainty. I’d never seen many tokusatsu films or TV shows, and what I had seen I hadn’t cared for. (‘Tokusatsu’ literally means something like ‘special effects,’ but in the West it’s come especially to refer to shows like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider.) Still, playing in the De Sève Cinema was Garo — Under the Moonbow (Garo: gekkô no tabibito, 牙狼 — 月虹ノ旅人, also translated Garo: Moonbow Traveler), written and directed by Keita Amemiya. It’s the latest installment of a franchise, created by Amemiya, which began with a 2005 TV series and has continued through more TV shows, live-action movies, and anime series. as well as video games, manga, and various other tie-ins. A veteran creator of tokusatsu dramas, Amemiya is particularly known for his powerful design sense, and the images and description of the film promised a stylish fantasy adventure. Although it’d be my first experience with a series that had dozens of hours of continuity behind it, I decided it was worth passing up a chance to see The Crow on the big screen in order to watch Under the Moonbow.

The movie’s about Reiga Saezima (Masei Nakayama), one of an order of warriors, the Makai Knights, who protect humanity from monsters called Horrors. Superhumanly powerful, he becomes even stronger when wearing his suit of special golden armour — which is unfortunately corrupted by evil not long after the movie opens. Saezima has to purify it, but also must save his true love (Natsumi Ishibashi), who has been abducted by Horrors. Yet as he fights his way through a bizarre train, even more plots boil away, leading ultimately to a fantastic battle involving secrets of his lineage.

The first thing to say is that the film’s easily understood without any prior knowledge of the franchise. I suspect that the climax will have more weight for people familiar with the world and with certain characters who appear there, but everything’s set up well enough in the film itself. Exposition’s delivered cleanly, and does not overbalance the plot. The complexities of the world are dramatised well, and if in an absolute sense evil still remains to be fought, at least the main antagonist of this particular story is dealt with.

Beyond that, the plot’s nicely-worked. The tale keeps expanding as the film goes on, sprouting subplots. A range of characters get moments of their own in which to shine; everyone does something important in bringing matters to a happy ending. Rules of this fantasy are established, and followed logically in ways that bring out unexpected wrinkles. Importantly, new ideas and images are always emerging,

My first movie on July 30 was the first feature by two French directors of independent short films, Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel. Jessica Forever, which the duo wrote as well as directed, is set in a near future in which disaffected and violent youth, mostly male, roam empty suburbs. The law hunts them down with killer drones, and the movie opens with a cloud of drones after one man, Kevin (Eddy Suiveng), who has squatted in an empty house. He’s saved from the law by a mysterious woman named Jessica (Aomi Muyock) and her squad of young men, who welcome Kevin into the fold.

My first movie on July 30 was the first feature by two French directors of independent short films, Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel. Jessica Forever, which the duo wrote as well as directed, is set in a near future in which disaffected and violent youth, mostly male, roam empty suburbs. The law hunts them down with killer drones, and the movie opens with a cloud of drones after one man, Kevin (Eddy Suiveng), who has squatted in an empty house. He’s saved from the law by a mysterious woman named Jessica (Aomi Muyock) and her squad of young men, who welcome Kevin into the fold.

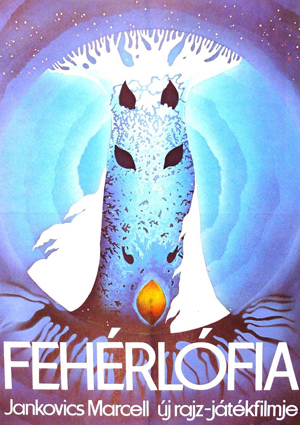

The last of the four movies I had on my schedule for July 29 promised to be interesting on any number of levels. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is an animated film made in 1981 by Hungarian Marcell Jankovics, directed by him from a script he wrote with László György. It’s based on the work of poet László Arany and folktales of the Magyars and Avars; Jankovics, who has published 15 books on comparative mythology, picked and chose from among the various versions of the tale to create what he wanted — a weird, protean, eye-popping, archetypal light show.

The last of the four movies I had on my schedule for July 29 promised to be interesting on any number of levels. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is an animated film made in 1981 by Hungarian Marcell Jankovics, directed by him from a script he wrote with László György. It’s based on the work of poet László Arany and folktales of the Magyars and Avars; Jankovics, who has published 15 books on comparative mythology, picked and chose from among the various versions of the tale to create what he wanted — a weird, protean, eye-popping, archetypal light show.

My third screening on July 29 was a double-feature at the De Sève Cinema of two animated movies, a long short and a short feature. “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” (ある日本の絵描き少年) is 20 minutes long. Twilight, which I immediately came to think of as (Not That) Twilight (and in fact some places online translate the title 薄暮, Hakubo, as Project Twilight), is 53 minutes long. They’re both slice-of-life films about young people in Japan making art, but are otherwise very different narratively and visually. Which is to say they have enough in common and enough contrast to make a fine double bill.

My third screening on July 29 was a double-feature at the De Sève Cinema of two animated movies, a long short and a short feature. “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” (ある日本の絵描き少年) is 20 minutes long. Twilight, which I immediately came to think of as (Not That) Twilight (and in fact some places online translate the title 薄暮, Hakubo, as Project Twilight), is 53 minutes long. They’re both slice-of-life films about young people in Japan making art, but are otherwise very different narratively and visually. Which is to say they have enough in common and enough contrast to make a fine double bill.