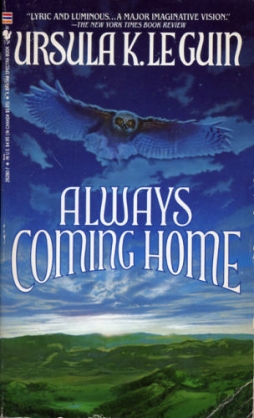

The Literature of Ideas: Always Coming Home

These past two weeks I’ve found myself writing here about science fiction, or speculative fiction, as the literature of ideas. It seems to me that ‘the literature of ideas’ implies something other than what we normally find in sf; I feel that it suggests writing that uses ideas to establish the structure of a work, instead of relying on traditional narrative. I’ve found a couple of early examples in Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker and Jack London’s The Iron Heel. As a way to wrap up the discussion, I thought this week I’d look at a more recent example of what I mean by the literature of ideas: Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home.

These past two weeks I’ve found myself writing here about science fiction, or speculative fiction, as the literature of ideas. It seems to me that ‘the literature of ideas’ implies something other than what we normally find in sf; I feel that it suggests writing that uses ideas to establish the structure of a work, instead of relying on traditional narrative. I’ve found a couple of early examples in Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker and Jack London’s The Iron Heel. As a way to wrap up the discussion, I thought this week I’d look at a more recent example of what I mean by the literature of ideas: Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home.

The book’s mostly set in a post-apocalyptic or at least post-industrial future, on the Pacific coast of the United States. It examines the folkways of the people called the Kesh, giving examples of their dramas and poems, examining their way of thinking and symbol-systems, and, since autobiography is one of the arts practiced by the Kesh, incidentally giving the life story of several members of the culture — most notably the extended narrative of a woman called Stone Telling. Stone Telling’s tale can easily be seen as the backbone of the book; divided into three parts, it functions as a recurring structural element that ties the mass of material together. But the book also has the feel of a well-stuffed anthology, a collection of fables and lore and myth that make the people as a whole come alive. And, as well, there are brief sections in which Le Guin herself ruminates on the difficulties and joys of writing this sort of “archaeology of the future” when the future does not yet exist, and must be imagined.

Here is how this morsel describes himself:

Here is how this morsel describes himself:

You can read my

You can read my