Vintage Treasures: Explorers and The Furthest Horizon, edited by Gardner Dozois

|

|

Last week I talked about two of my favorite anthologies by one of the most acclaimed editors in the field: The Good Old Stuff (1998) and The Good New Stuff (1999) (collected into one massive 982-page volume as The Good Stuff by the Science Fiction Book Club in 1999), both edited by Gardner Dozois. Those books collected some of the best adventure SF from the last century, alongside Dozois’ detailed and affectionate commentary on each author. The result was the equivalent of a Master’s level course in Adventure SF of the 20th Century, and its most proficient writers.

A year later, Dozois did the same thing with another pair of anthologies, this time focused on two similarly fascinating branches of science fiction: tales of deep space exploration, and tales of the far future. Like the first two volumes, they were both released in trade paperback from St. Martin’s/Griffin, and they are both excellent:

Explorers: SF Adventures to Far Horizons (495 pages, April 2000, $17.95)

The Furthest Horizon: SF Adventures to the Far Future (492 pages, May 2000, $17.95)

Both had covers by famous SF artist Chesley Bonestell. Like the first volumes, they include Dozois’ lengthy and highly informative intros to each story. These volumes perfectly compliment the first two, forming the basis for a solid library of modern science fiction.

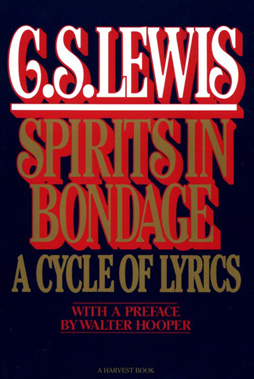

This is the third in a series of posts about the fictions of C.S. Lewis.

This is the third in a series of posts about the fictions of C.S. Lewis.

Yesterday I began a series of posts looking at the fiction of C.S. Lewis. Lewis has an unusually varied body of work, and I intend to wander through it chronologically and see what leaps out at me.

Yesterday I began a series of posts looking at the fiction of C.S. Lewis. Lewis has an unusually varied body of work, and I intend to wander through it chronologically and see what leaps out at me.