Fantastic Reference and Non-fiction Books

At the centre of all the fuzzy sets is a rough definition of what we mean by fantasy: a fantasy text is a self-coherent narrative which, when set in our REALITY, tells a story which is impossible in the world as we perceive it (see PERCEPTION); when set in an OTHERWORLD or SECONDARY WORLD, that otherworld will be impossible, but stories set there will be possible in the otherworld’s terms. An associated point, hinted at here, is that at the core of fantasy is STORY. Even the most surrealist of fantasies tells a tale.

— from the foreword of The Encyclopedia of Fantasy by John Clute and John Grant

I like to think I have a fairly extensive knowledge of swords & sorcery and other fantasy sub-genres. While I never took courses on the hermeneutics of Conan, or Fafhrd and post-modernism, I do have about forty years of time on job reading the stuff. When I write I try to bring that knowledge to bear in a close reading of the story. But I know better than to rely just on my brain all the time, so sometimes I turn to my small but valuable collection of fantasy non-fiction titles.

I like to think I have a fairly extensive knowledge of swords & sorcery and other fantasy sub-genres. While I never took courses on the hermeneutics of Conan, or Fafhrd and post-modernism, I do have about forty years of time on job reading the stuff. When I write I try to bring that knowledge to bear in a close reading of the story. But I know better than to rely just on my brain all the time, so sometimes I turn to my small but valuable collection of fantasy non-fiction titles.

I have always loved reference books. When I was little I pestered my mother to buy me several sets of books, starting with the Golden Book Illustrated Dictionary and followed by the Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia. The latter was bought, one volume every few weeks, at A&P. Sadly, she didn’t get two of them: Vol.14, ISRAE to LACCA, and Vol.21, RUSSI to SUMAL. Which meant I didn’t learn much about Kipling or rutabagas until I was older. I spent hours upon hours poring over those books, just reading about whatever was in front of me.

That initial love for reference books only grew as I got older, eventually extending into the various genres of fiction I read. I’ve got several good books on crime fiction and science fiction that have steered me toward books I might never have otherwise known about or been willing to give a chance. Writing about swords & sorcery for the past four and half years, though, it’s the fantasy references that I’ve drawn on the most for ideas and information.

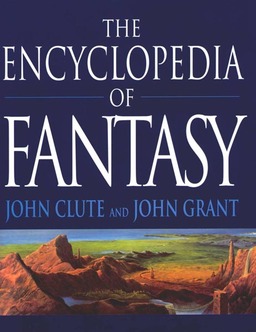

The big megilla on the shelf is John Clute and John Grant’s massive (1048 pages!) The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997). While dated now and available free on-line, I have never regretted the $75 it cost me. Aside from being insanely comprehensive, it takes the genre seriously. Not only does it provide biographies, bibliographies, and analyses of authors, it examines various sub-genres, themes, and motifs. They even developed their own literary terms for things heretofore undefined which I have absorbed into my own ruminations on the genre. One is CROSSHATCH, meaning a story where the border between the fantastic and mundane is fuzzy, an example being Emma Bull’s The War for the Oaks. Another is WAINSCOT, refering to beings living just underneath the surface of everyday society. The most literal example of this is Mary Norton’s The Borrowers.

The big megilla on the shelf is John Clute and John Grant’s massive (1048 pages!) The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997). While dated now and available free on-line, I have never regretted the $75 it cost me. Aside from being insanely comprehensive, it takes the genre seriously. Not only does it provide biographies, bibliographies, and analyses of authors, it examines various sub-genres, themes, and motifs. They even developed their own literary terms for things heretofore undefined which I have absorbed into my own ruminations on the genre. One is CROSSHATCH, meaning a story where the border between the fantastic and mundane is fuzzy, an example being Emma Bull’s The War for the Oaks. Another is WAINSCOT, refering to beings living just underneath the surface of everyday society. The most literal example of this is Mary Norton’s The Borrowers.

Even in this day of instantaneous information courtesy of Google and a million-billion sites, I find Clute and Grant’s book a tremendous resource. Well cross-referenced, footnoted, and accurate, it also lacks the haphazard randomness of the web and has proven an invaluable tool and guide over the years.

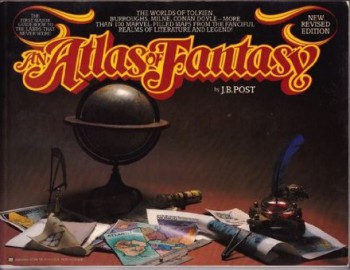

J.B. Post’s An Atlas of Fantasy is a joy to leaf through. Post was the map librarian for the Free Library of Philadelphia and the 1973 first edition of his compendium of fantastic maps was from author Jack Chalker’s Mirage Press. The later edition in 1979 came from Ballantine with a foreword by Lester del Rey. While I don’t agree with del Rey’s claim that not including a map in a fantasy book is a bad thing which forces the reader to “attempt his own mental cartography, or remain hopelessly vague about much of the developement of the story,” I do love fantasy maps. From my first sight of Tolkien’s own maps in The Hobbit, I’ve been hooked. They served to draw me into the story as much as any other element, making me believe for a few hundred pages that Beorn’s Carrock was a real place, Rivendell existed, and Esgaroth stood on its pilings on the Long Lake.

J.B. Post’s An Atlas of Fantasy is a joy to leaf through. Post was the map librarian for the Free Library of Philadelphia and the 1973 first edition of his compendium of fantastic maps was from author Jack Chalker’s Mirage Press. The later edition in 1979 came from Ballantine with a foreword by Lester del Rey. While I don’t agree with del Rey’s claim that not including a map in a fantasy book is a bad thing which forces the reader to “attempt his own mental cartography, or remain hopelessly vague about much of the developement of the story,” I do love fantasy maps. From my first sight of Tolkien’s own maps in The Hobbit, I’ve been hooked. They served to draw me into the story as much as any other element, making me believe for a few hundred pages that Beorn’s Carrock was a real place, Rivendell existed, and Esgaroth stood on its pilings on the Long Lake.

I suspect del Rey chose to publish a new version of this book in 1979 as part of his ongoing effort to commoditize fantasy fiction, and as such it might be easily dismissed. But it’s too idiosyncratic a book and too clearly a labor of love to do that. For every map of Middle-earth, Barsoom, and Narnia, there’s one of More’s Utopia, Trollope’s Barsetshire, and Mongo. Some of the maps are by the authors, others by hired artists, and some by fans (one of those being a map of Narnia drawn by my friend Jason’s father!). While no longer in print, reasonably priced copies are available.

Next are two books I link together mostly because I bought them both from the same discount bin in a comic store twenty years ago: James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock’s Fantasy: The 100 Best Books (1988) and David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels (1988). Each book’s value lies in its authors’ wide-ranging definition of fantasy. Genre classics sit side by side with fantastic excursions by more mainstream writers such as Brian Moore and Kingsley Amis. Like Clute and Grant they respect the genre and treat its pulpy roots as seriously as its literary ones. Without them I might never have read anything by Henry Treece (see my reviews here) or Alasdair Gray’s staggering work of madness and artistry, Lanark.

Next are two books I link together mostly because I bought them both from the same discount bin in a comic store twenty years ago: James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock’s Fantasy: The 100 Best Books (1988) and David Pringle’s Modern Fantasy: The Hundred Best Novels (1988). Each book’s value lies in its authors’ wide-ranging definition of fantasy. Genre classics sit side by side with fantastic excursions by more mainstream writers such as Brian Moore and Kingsley Amis. Like Clute and Grant they respect the genre and treat its pulpy roots as seriously as its literary ones. Without them I might never have read anything by Henry Treece (see my reviews here) or Alasdair Gray’s staggering work of madness and artistry, Lanark.

Cawthorn’s book (in the foreword Moorcock states that most of the work and writing of the book was his co-author’s) starts with Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), and works its way through various Gothic, Romantic, and Victorian works before inching toward pulp extravaganzas of the 20th century. Its final selection is Expecting Someone Taller (1987) by Tom Holt.

Pringle was a member of the Interzone collective (as had been John Clute). Through their magazine, also called Interzone, they hoped to continue the groundbreaking work of New Worlds which, under Michael Moorcock’s editorship between 1964-1969, had been a voice for modernism and experimentation in science fiction literature. His choice of 100 novels is both more literary and less American than many such lists tend to be. It starts with Mervyn Peake’s 1947 Titus Groan and works its way up to John Crowley’s 1987 novel, Aegypt. Cheek-by-jowl sit John Myers Myers’ Silverlock, Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman, Fritz Leiber’s The Swords of Lankhmar, and Thomas Disch’s The Businessman.

Pringle was a member of the Interzone collective (as had been John Clute). Through their magazine, also called Interzone, they hoped to continue the groundbreaking work of New Worlds which, under Michael Moorcock’s editorship between 1964-1969, had been a voice for modernism and experimentation in science fiction literature. His choice of 100 novels is both more literary and less American than many such lists tend to be. It starts with Mervyn Peake’s 1947 Titus Groan and works its way up to John Crowley’s 1987 novel, Aegypt. Cheek-by-jowl sit John Myers Myers’ Silverlock, Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman, Fritz Leiber’s The Swords of Lankhmar, and Thomas Disch’s The Businessman.

Michael Moorcock’s Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy is a maddening, infuriating work by one of the most important and influential authors of fantasy. From teenaged editor of Tarzan Adventures and compiler of The Sexton Blake Library, to creator of the Eternal Champion cycle, to his aforementioned editorship of New Worlds, he is a man who has done much to shape the modern fantasy genre. He is also a man of strong opinions and no wish to obscure them.

Though this book provides an overview of the birth and evolution of epic fantasy, Moorcock pauses along the way to make his feelings clear on various authors and their works. Chapter 5 is a reworked version of his most famous piece of non-fiction, the 1978 essay, “Epic Pooh.” It includes furious attacks on Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Richard Adams for what he sees as numerous flaws in their works and betrayals of the “romantic discipline.”

The 2004 edition includes eight reviews of books Moorcock considers worthy of note. Most are contemporary, including K.J. Bishop’s The Etched City (just mentioned by John O’Neill the other day), and Jeff VanderMeer’s Veniss Underground. But the first is Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. Published in 1954, the same year as The Fellowship of the Ring, he holds it up as exactly the model of the mythically resonant, bloody story he prefers. He claims that along with “Peake, Henry Treece and even T. H. White, Anderson influenced a school of epic fantasy fundamentally at odds with inkling reassurances.”

The 2004 edition includes eight reviews of books Moorcock considers worthy of note. Most are contemporary, including K.J. Bishop’s The Etched City (just mentioned by John O’Neill the other day), and Jeff VanderMeer’s Veniss Underground. But the first is Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. Published in 1954, the same year as The Fellowship of the Ring, he holds it up as exactly the model of the mythically resonant, bloody story he prefers. He claims that along with “Peake, Henry Treece and even T. H. White, Anderson influenced a school of epic fantasy fundamentally at odds with inkling reassurances.”

Harold Bloom is a towering figure in contemporary American literary criticism, having written extensively on the Western Canon in general, Shakespeare, the Bible, along with countless other subjects. Twelve years ago he gained some notoriety among genre readers when he condemned the National Book Foundation for awarding Stephen King its annual award. He’s also a huge fan of David Lindsay’s Voyage to Arcturus, going as far as writing a sequel, The Flight to Lucifer, which he subsequently said is weak.

Somewhere he found the time to edit Modern Fantasy Writers. For each author covered a biography and bibliography is provided. Most valuable, though, are the comments of various critics and authors about the writer in question. Along with the usual suspects like Tolkien, Lewis, and Howard, are Bradbury, Collier, Charles Williams, and several others less well known these days.

Finally, L. Sprague de Camp’s Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy. It’s as opinionated as Moorcock’s book but without the former’s vim and vigor. There’s a pedantic tone to his writing that can be wearing in long doses. Still, he was a man of tremendous knowledge and deeply held opinions, with a lot to say about the genre.

Finally, L. Sprague de Camp’s Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy. It’s as opinionated as Moorcock’s book but without the former’s vim and vigor. There’s a pedantic tone to his writing that can be wearing in long doses. Still, he was a man of tremendous knowledge and deeply held opinions, with a lot to say about the genre.

This book also has a more limited goal. While Moorcock provides a historical survey of the genre extending back to its roots in the Renaissance and Romantic eras, de Camp is interested in a few specific authors, primarily from the first part of the 20th century. These include William Morris, Lord Dunsany, H.P. Lovecraft, E.R. Eddison, Robert E. Howard, Fletcher Pratt, Clark Ashton Smith, J.R.R. Tolkien, and T. H. White. While I would argue Lovecraft and White in particular, great as they are, are definitely not among the “makers of heroic fantasy,” their presence is part of what makes this volume worthwhile. It’s the odd choices reflecting de Camp’s personal opinions that give Literary Swordsmen its unique flavor differentiating it from any other list of “important authors.”

While de Camp brings the 5¢ psychiatry he’s infamous for to his chapters on Lovecraft and Howard, he provides a wealth of information for them and the other authors as well. When I finally get around to reading Morris’ The Sundering Flood and Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros I’ll be glad I have this to give me some insight and context.

While de Camp brings the 5¢ psychiatry he’s infamous for to his chapters on Lovecraft and Howard, he provides a wealth of information for them and the other authors as well. When I finally get around to reading Morris’ The Sundering Flood and Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros I’ll be glad I have this to give me some insight and context.

All of these books are written by authors with strong opinions that compel me to examine and understand my own. When David Pringle calls Lord Foul’s Bane an “unearned epic” and Michael Moorcock derides Lloyd Alexander’s writing as cliched and flaccid I can’t just say both are wrong without digging into my own reasoning as well as theirs.

I’m always on the lookout for more books of this ilk. Once upon a time I had a copy of Baird Searle’s A Reader’s Guide to Fantasy, long since lost, and I should replace it. If anyone has any other suggestions, please let me know.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read his thoughts about epic high fantasy here.

This is an excellent post. I love The Encyclopedia of Fantasy; my increasingly-battered paper copy is still well-used, even if it is all duplicated and updated online. Wizardry & Wild Romance, on the other hand, is a book I disliked enough that I sometimes think of writing about it here; but it seems too shapeless to really wrestle with (besides, it’d probably just exasperate me if I tried to go on about it at length).

I didn’t know Bloom had done a book about Modern Fantasy Writers! I’ve got another book he edited about *Classic* Fantasy Writers; happy to know there’s a companion. I’ve also seen a book he edited on C.S. Lewis, in his “Modern Critical Views” series; it’s interesting, in that his only contribution seems to be a prologue about how much he disliked Lewis personally and how he doesn’t think Lewis was a good writer. Kind of unclear why he put out the book.

As for other reference works … have you seen Alberto Manguel’s Dictionary of Imaginary Places? It’s a list of places in fantasy novels supposedly set in this world, with the entries written as though they were guides for travellers. A wide range of stuff in there, including some maps.

Fantasy Book by Rottensteiner

Ultimate Encyclopedia Of Fantasy by Pringle (quite a few versions of this)

100 Must-Read Fantasy Novels by Rennison & Andrews

The last one is a slightly more crowdpleasing selection but nonetheless has some interesting ones and further notes on books on certain themes.

Ursula Le Guin’s The Language of the Night has a number of informative essays on fantasy (and on science fiction), including “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie”, which dissects and discusses the importance of Style in fantasy works (much to the detriment of the Deryni books by Katherine Kurtz, which are adduced as a “How Not To” example, though apologetically).

And a big second for Baird Searle’s A Reader’s Guide for both fantasy and science fiction, which led me, among other works, to Jane Gaskell’s Atlan saga, also being re-read on Black Gate there days.

The Dictionary of Imaginary Places is a wonderful book. Another excellent book is the Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural. It was published in 1986 and I don’t think its ever been reprinted. I grabbed mine off of a remainder pile many years ago…

@Matthew – Thanks, glad you liked it. I bought the Moorcock book with no knowledge of “Epic Pooh” and was taken aback by his virulent hatred for anything that smacks of “the Lamb or the Lion” as he put it. It’s far more a matter of religion and politics than artistic judgment.

I’ve seen the Manguel book and looking at it on Amazon know I need a copy now.

@Robert – Thanks, they all look interesting. That’s exactly the kind of info I was hoping to get.

@Eugene – I keep meaning to get and then forgetting to get a copy of the LeGuin – everyone’s always talking about the Elfland essay.

I had both the Searles books. While I still haven’t read them, he’s the reason I bought the Atlan books as well.

Great article. Each title is a solid choice.

To those I would add ~

Fantasy of the 20th Century: An Illustrated History by Randy Broecker.

Encyclopedia of Fantasy And Horror Fiction

by Don D’Ammassa.

Realms of Fantasy by Robert Holdstock & Malcolm Edwards.

The A to Z of Fantasy Literature by Brian Stableford.

[…] Black Gate has a list of fantastic reference and non-fiction books. […]

@Thomas – The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural looks interesting. That Jacques Barzun was involved is intriguing.

@James K – thanx for the suggestions. The Stableford looks particularly good. I wish all of these various suggestions were available as e-books as I’ve pretty much run out of shelf space.