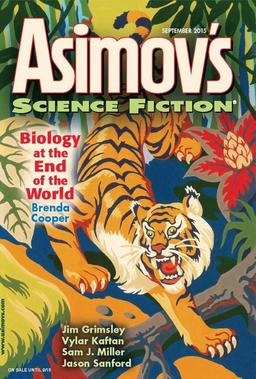

September 2015 Asimov’s Science Fiction Now on Sale

Asimov’s Science Fiction has a spiffy new website this month, with loads of new content — including issue and individual story summaries, a vintage cover gallery (cool!), and lots more. You should check it out. Here’s what they say about the latest issue:

Asimov’s Science Fiction has a spiffy new website this month, with loads of new content — including issue and individual story summaries, a vintage cover gallery (cool!), and lots more. You should check it out. Here’s what they say about the latest issue:

Brenda Cooper’s lead story in our September 2015 issue looks at the lines we draw between ethics and scientific research. A deadly clash between forces making last ditch efforts to preserve life as we know it and renegades involved in potentially dangerous, but possibly life saving, experimentation will ultimately determine what will be the “Biology at the End of the World”!

Distinguished author Jim Grimsley returns to Asimov’s with a terrifying depiction of “The God Year”; Nebula Award winner Vylar Kaftan exposes us to an arctic chill on “The Last Hunt”; Sean Monaghan’s “The Molenstraat Music Festival” paints a far future of exquisite invention that hasn’t lost touch with the beauty of art; Jason Sanford’s “Duller’s Peace” imagines a far less happy future where even thoughts are under government surveillance; new to Asimov’s, author Sam J. Miller looks at lives upended by drastic climate change in “Calved”; and Peter Wood lightens our mood as he chronicles the story of a single mother and her young son out “Searching for Commander Parsec.”

And there’s more… Robert Silverberg’s Reflections hands us the key to “The Sixth Palace!”; Paul Di Filippo’s On Books investigates the short form, with a look at collections by Robert Silverberg and Delia Sherman, as well as a new Dozois/Martin anthology; plus we have an array of poetry and other features you’re sure to enjoy.

The only things missing are a cover credit, and a convenient link to last issue’s contents… which I’m sure is there somewhere, I’m just damned if I can find it. Also, every single TOC link in our past Asimov’s SF coverage is now defunct, which is annoying.