Fantasia 2018, Day 4, Part 2: Cold Skin and L’Inferno

My third movie on Sunday, July 15, was a France-UK co-production called Cold Skin. It was scheduled to start at 5:10 in the Hall Theatre, and ran 107 minutes. At 7:15, across the street at the De Sève, there’d be a showing of the 1911 Italian film L’Inferno, an adaptation of the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Musical accompaniment to the silent film would be provided by Maurizio Guarini of Italian prog band Goblin, well-known for providing the soundtrack to Dario Argento’s Suspiria among many other films. I figured I had a shot at getting in to see L’Inferno, but it’d depend on the length of the line-up. In the meanwhile, I was quite looking forward to Cold Skin.

My third movie on Sunday, July 15, was a France-UK co-production called Cold Skin. It was scheduled to start at 5:10 in the Hall Theatre, and ran 107 minutes. At 7:15, across the street at the De Sève, there’d be a showing of the 1911 Italian film L’Inferno, an adaptation of the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Musical accompaniment to the silent film would be provided by Maurizio Guarini of Italian prog band Goblin, well-known for providing the soundtrack to Dario Argento’s Suspiria among many other films. I figured I had a shot at getting in to see L’Inferno, but it’d depend on the length of the line-up. In the meanwhile, I was quite looking forward to Cold Skin.

Directed by Xavier Gens, the screenplay by Jesús Olmo and Eron Sheehan was based on the Catalan novel La Pell Freda by Albert Sánchez Piñol. It follows an unnamed man (David Oakes), presumably English, eventually to be known as Friend, as he travels by ship to an isolated island in the far south where he will take detailed meteorological readings. It is September 1914, and elsewhere the First World War’s begun; on the island Friend finds, there is no other human inhabitant but a surly lighthouse-keeper named Gruner (Ray Stevenson, perhaps best known for his role as Volstagg in the Thor movies). As Friend soon finds out, though, there are humanoid but non-human inhabitants: fish-creatures that come out at night and attack. Friend finds Gruner keeps a fish-woman (Aura Garrido) as a slave, but must live with him and the creature he names Aneris as, night after night, the other humanoids attack Gruner’s fortified lighthouse.

The first thing that must be said about this film is that it looks spectacular. The landscape of the island is harsh, craggy, barren, and beautiful. Friend’s cabin and Gruner’s lighthouse look lived-in and, crammed with detail, fit their period perfectly. There’s a kind of tactile 1914 that comes out of this movie, particularly the early scenes, before that external world is as it were stripped away from the humans. It’s a realisation of the era that seems to owe nothing to Merchant-Ivory or traditional period films; it’s harder-edged, unyielding. The lighting and cinematography are haunting and perfect: there’s a sense of place to the island built by the quality of sunlight, and a character to the interior scenes (and rare underwater scenes) as the light shifts.

The next thing that has to be said is that the acting in no way takes a back seat to the images. Oakes, Stevenson, and Garrido build complex characters and establish complex relationships among them — relationships that build and change over the course of the film. Garrido’s worth particular mention here, as her character is functionally mute yet always comprehensible. But all three capably bring out the dynamics among the characters that drive the plot, notably the tense not-quite adversarial relationship between Friend and Gruner.

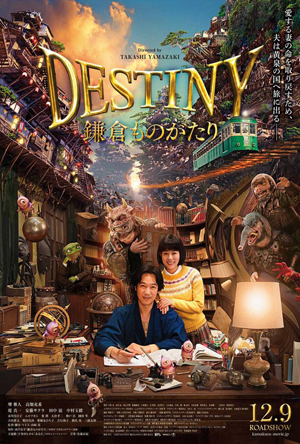

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.