Fantasia 2019, Day 5, Part 4: SHe

The fourth and last movie I saw on July 16 was the most experimental movie I’d seen at Fantasia, not only this year but possibly in all the time I’ve been going to the festival. Before that feature, though, was a short almost as strange.

The fourth and last movie I saw on July 16 was the most experimental movie I’d seen at Fantasia, not only this year but possibly in all the time I’ve been going to the festival. Before that feature, though, was a short almost as strange.

“Bavure” was directed and written by Donato Sansone. An animator’s hand mixes paints, makes an image, then remakes it, then remakes that, and so on through an increasingly cosmic story. A woman is made pregnant, a child comes out, and becomes an astronaut, and meets aliens, and on to a bleak climax. ‘Bavure’ means smear, or mistake, and the imagery of an animator remaking a smear of paints into a series of images fits. The animation technique’s a striking and effective way to move from image to image, the story’s cute, and at 5 minutes the film doesn’t outlast its welcome.

Next was the feature. It was called SHe, a movie directed, written, and edited by Zhou Shengwei. A work of stop-motion animation, Zhou made 268 models for the film himself, and took 58,000 photos over the course of 6 years to make it.

The film’s a staggering work of imagination. None of the characters are remotely human. They are, in fact, based on shoes. In a world of strange creatures assembled from everyday objects, entities based off of men’s shoes oppress entities based off of women’s shoes. One of the latter escapes and has a daughter, but the mother has to find a way to get the resources to feed the child. Only by adopting a disguise as a man’s shoe and entering into the dreadful danger of a pseudo-capitalist workplace can the two survive. But strange things happen in the workplace: the lady-shoe does not fit in, but turns out to have abilities the other worker-shoes don’t, attracting the attention of the boss of the shoes — who then draws her into an even stranger behind-the-scenes world where the tables start to turn.

At least that’s how I understand the basic plot. The film has no dialogue (vocal sounds come from Lv Fuyang), and the lack of human features on the characters give the audience some space to find their own meanings for things. The body language of these creatures is I think relatively clear, but it still requires some focus to follow events. Or it did for me; perhaps that’s a function of how I parse images as opposed to words.

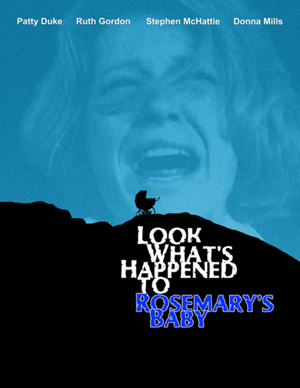

It’s relatively unusual for me to watch a movie that I know going in is not good. But every so often, and usually at Fantasia, something bizarre comes along that looks bad but also in its way promising. So it was that for my third film of July 16 I settled in at the De Sève Theatre for a screening of the rare 1976 TV-movie sequel to Rosemary’s Baby: an opus directed by Sam O’Steen titled Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby. Star Stephen McHattie was in attendance, and would stick around to take our questions after the film.

It’s relatively unusual for me to watch a movie that I know going in is not good. But every so often, and usually at Fantasia, something bizarre comes along that looks bad but also in its way promising. So it was that for my third film of July 16 I settled in at the De Sève Theatre for a screening of the rare 1976 TV-movie sequel to Rosemary’s Baby: an opus directed by Sam O’Steen titled Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby. Star Stephen McHattie was in attendance, and would stick around to take our questions after the film.

For my second movie of July 15 I went to the Fantasia screening room to watch the Cambodian film The Prey. Directed by Jimmy Henderson from a script by Henderson with Michael Hodgson and Kai Miller, this is a film that traces its narrative lineage back to Richard Connell’s immortal “The Most Dangerous Game.” In this case, the game’s played in the wilds of Cambodia, and the rules turn out to be surprisingly complex — and the number of players surprisingly large.

For my second movie of July 15 I went to the Fantasia screening room to watch the Cambodian film The Prey. Directed by Jimmy Henderson from a script by Henderson with Michael Hodgson and Kai Miller, this is a film that traces its narrative lineage back to Richard Connell’s immortal “The Most Dangerous Game.” In this case, the game’s played in the wilds of Cambodia, and the rules turn out to be surprisingly complex — and the number of players surprisingly large.