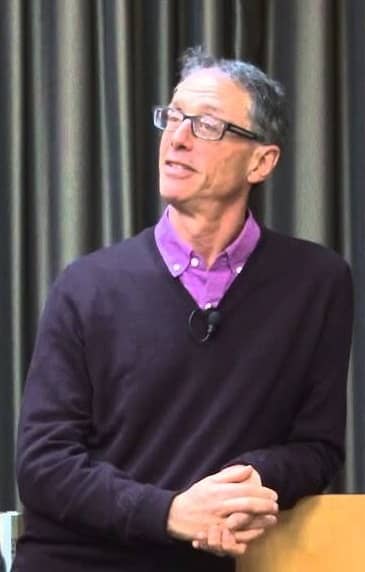

A Wide Range of Stories: John DeNardo on the Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Books in October

|

|

|

In his intro to his book roundup for October over at Kirkus Reviews, John DeNardo says:

I’m constantly surprised at the wide range of stories offered within the science fiction and fantasy genres. Just take a look at this month’s top science fiction and fantasy picks and you’ll see what I mean.

He’s certainly got a point. SF and fantasy fans are constantly making up new sub-genres and sub-sub-genres to categorize just what the hell we read every month (Weird Western, Urban Fantasy, Sword-and-Planet, Space Opera, Steampunk, Cyberpunk, Ghostpunk, Elfpunk…), and it still seems that half the new stuff is just flat-out uncategorizable.

October’s new SF & Fantasy is no different. Over at the Barnes & Noble Sci-Fi and Fantasy Blog Jeff Somers catalogs 29 October titles by Tade Thompson, Cixin Liu, Tim Pratt, Theodora Goss, and our very own Derek Künsken, but John takes a different tack, narrowing his focus to The 7 Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Books to Read This October. Here’s a few highlights from his suggestions.