Fantasia 2016, Day 4: Questioning Genre (Beware the Slenderman, In a Valley of Violence, and The Unseen)

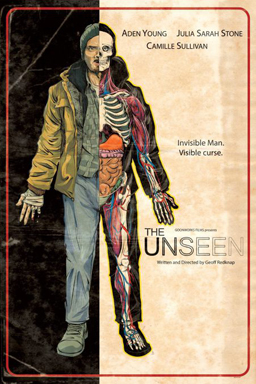

Sunday, July 17, began early for me. I went down to the Hall Theatre to watch Parasyte: Part 2 (I’ve written about it here, along with Part 1), then took care of some personal errands before returning to the Hall to watch a documentary called Beware the Slenderman, about a case of attempted murder and its apparent inspiration in internet stories about a shadowy monster. After that I planned to watch In a Valley of Violence, a Western starring Ethan Hawke, John Travolta, and Karen Gillan. Then I’d go across the street to see the world premiere of a Canadian film called The Unseen, which promised a new take on the idea of the invisible man.

Sunday, July 17, began early for me. I went down to the Hall Theatre to watch Parasyte: Part 2 (I’ve written about it here, along with Part 1), then took care of some personal errands before returning to the Hall to watch a documentary called Beware the Slenderman, about a case of attempted murder and its apparent inspiration in internet stories about a shadowy monster. After that I planned to watch In a Valley of Violence, a Western starring Ethan Hawke, John Travolta, and Karen Gillan. Then I’d go across the street to see the world premiere of a Canadian film called The Unseen, which promised a new take on the idea of the invisible man.

Beware the Slenderman, directed by Irene Taylor Brodsky, is an examination of a crime that took place in small town in Wisconsin on May 31, 2014. Two twelve-year-old girls took a mutual friend out to a nearby forest and stabbed her fourteen times before leaving her to die. The girls believed they were acting in the service of a terrifying creature called the Slender Man. Brodsky’s film examines the causes of the crime, presenting the background of the stories of the Slender Man before analysing the family life and mental health of the two girls, and then following the girls for a time through the justice system.

Doubts about the film immediately arise. There are elements of mystery in its structure — why did these children do this thing? — that really does it no favours. The film ends up focussing on the girls’ mental states, so the mystery aspect ultimately feels superficial at best and exploitative at worst. It’s hard as well not to notice that there’s no involvement from the victim or her family. One might wonder if the film also exploits fears about the neurodivergent. The narrative it settles on, the explanation of what led to the killing, involves undiagnosed mental conditions on the part of the two girls. This is a plausible analysis, to say the least, but what’s the film doing by presenting it? What is the point of telling this story?

This isn’t a neutral examination of all the factors and causes behind the attack, though Brodsky and her team always remain silent and off-camera. There’s a clear sense of advocacy to the documentary, which is structured around the girls’ experiences in court leading up to a judgement about whether they should stand trial as adults — according to Wisconsin law, minors accused of attempted murder are to be tried as adults, meaning the girls could face prison sentences of sixty-five years if convicted. The film ends with the ruling, but one of the problems with the film is that it’s not at all clear how or in what way the decision will affect the girls’ psychological treatment going forward; we don’t know what would result in the best therapy for them.

This isn’t a neutral examination of all the factors and causes behind the attack, though Brodsky and her team always remain silent and off-camera. There’s a clear sense of advocacy to the documentary, which is structured around the girls’ experiences in court leading up to a judgement about whether they should stand trial as adults — according to Wisconsin law, minors accused of attempted murder are to be tried as adults, meaning the girls could face prison sentences of sixty-five years if convicted. The film ends with the ruling, but one of the problems with the film is that it’s not at all clear how or in what way the decision will affect the girls’ psychological treatment going forward; we don’t know what would result in the best therapy for them.

The film occasionally seems to be looking for other reasons for the crime, even to be searching for other culprits to indict. Discussions about the effect of the internet the young, and particularly on troubled youths, feel like facile generalisations about a deeply complex issue. At worst, there’s a whiff here of the old-fashioned habit of finding scapegoats for bad behaviour of the young or others: we used to say people did bad things under the influence of heavy metal or pornography or role-playing games or comic books or scary movies, now we say they did bad things because the internet drove them to it.

The discussion of the Slender Man him- or itself is more detailed, but ends up as an irrelevance. Early on the film spends a fair amount of time discussing the origin of the figure, a modern-day bogeyman that started in 2009 in a photoshop contest for the Somethingawful forum. The creature developed through a series of urban legends until a Slender Man mythology existed around the internet, in YouTube videos and DeviantArt accounts and 4chan message boards. Richard Dawkins is brought in to explain the nature of a meme, and Jack Zipes appears briefly to compare Slender Man to the folklore of the Brothers Grimm and to the Pied Piper story. Those are reasonably well-known names, the Slender Man gets a fair amount of screen time, and in the end it all feels beside the point. As described, the Slender Man had and has a fascination for the young and perhaps especially misfit or socially outcast youths. But it’s difficult to see the figure as a key motivator of events. The Slender Man is a story. The cause of the attack lies in the minds of the attackers.

The discussion of the Slender Man him- or itself is more detailed, but ends up as an irrelevance. Early on the film spends a fair amount of time discussing the origin of the figure, a modern-day bogeyman that started in 2009 in a photoshop contest for the Somethingawful forum. The creature developed through a series of urban legends until a Slender Man mythology existed around the internet, in YouTube videos and DeviantArt accounts and 4chan message boards. Richard Dawkins is brought in to explain the nature of a meme, and Jack Zipes appears briefly to compare Slender Man to the folklore of the Brothers Grimm and to the Pied Piper story. Those are reasonably well-known names, the Slender Man gets a fair amount of screen time, and in the end it all feels beside the point. As described, the Slender Man had and has a fascination for the young and perhaps especially misfit or socially outcast youths. But it’s difficult to see the figure as a key motivator of events. The Slender Man is a story. The cause of the attack lies in the minds of the attackers.

To an extent the film seems to understand that. There’s a no-nonsense feel to the discussion of the Slender Man, a shunning of atmosphere or a sense of horror. But I don’t think the film draws an effective connection between the Slender Man and the specific situation and personalities of the two girls. We can understand why they were drawn to the stories, but there’s still a randomness behind the connection. There are lots of stories the girls might have been drawn to; lots of horror stories; perhaps even a fair number of horror stories that might have similarly provoked a similar attack. It happened to be the Slender Man in this particular case. The movie does not establish the degree of relevance of these stories to the extent you’d expect, given its title and the presence of the Slender Man on its poster and indeed the amount of discussion the character gets in the film.

To an extent the film seems to understand that. There’s a no-nonsense feel to the discussion of the Slender Man, a shunning of atmosphere or a sense of horror. But I don’t think the film draws an effective connection between the Slender Man and the specific situation and personalities of the two girls. We can understand why they were drawn to the stories, but there’s still a randomness behind the connection. There are lots of stories the girls might have been drawn to; lots of horror stories; perhaps even a fair number of horror stories that might have similarly provoked a similar attack. It happened to be the Slender Man in this particular case. The movie does not establish the degree of relevance of these stories to the extent you’d expect, given its title and the presence of the Slender Man on its poster and indeed the amount of discussion the character gets in the film.

I will say that the characters of the two girls are built up very well. We see them being interviewed by the police after their arrest, and hear one of them on a phone call with her family. We are given well-chosen interviews with their parents, who are incredibly open about the process of coming to grips with what their daughters have done. There is an insistence on the humanity of the two girls at the same time as the film confronts the gravity of their action. A powerful interview with the father of one of the girls, who himself suffers from schizophrenia, humanizes the condition and goes some distance toward alleviating the sense of the exploitation of mental illness. And yet all this character work also tends to make the section on the Slender Man feel even more irrelevant — not simply a horror story distant from reality, but a minor cause in the pattern of occurences.

Writing up these diary entries in August, I happen to be in the process of reading Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s engagingly potty book The Black Swan, which is about improbable and unpredictable events. Part of his point is that there’s a human tendency to look for easy causes for things, however improbable and unpredictable those things in fact are, and to find those causes even though they’d have been invisible before the thing happened. Beware the Slenderman feels like one of these searches for a retroactively overdetermined cause, an unconscious straightening-out of the past to make the world feel safer. Less subject to unpredictable events. Less scary. To that extent, the explanation of a modern horror story as a key driver for events is symbolically right: the movie’s reacting against the horror of an uncertain, random world and finds a scapegoat in the idea of horror itself.

Personally, it seems to me that if anyone’s responsible, it’s the education system that allowed the severe mental issues of the two girls to go undetected for several years, despite the two clearly being outcast from their age group. But the movie chooses not to cast blame in that direction (nor does it look at other systemic issues — nothing here about gender or class, for example). I have to say that I found most affecting and unsettling the fact that the two girls have now become part of the Slender Man legend — near the end of the film we see that they’re now included in some of the Slender Man fan art and stories. What to make of that? I don’t know, and I don’t think the movie does either. Although this would seem to be directly relevant to the film’s theme, it shies away from analysing it, or indeed from examining the individuals or online communities fascinated with the Slender Man.

Personally, it seems to me that if anyone’s responsible, it’s the education system that allowed the severe mental issues of the two girls to go undetected for several years, despite the two clearly being outcast from their age group. But the movie chooses not to cast blame in that direction (nor does it look at other systemic issues — nothing here about gender or class, for example). I have to say that I found most affecting and unsettling the fact that the two girls have now become part of the Slender Man legend — near the end of the film we see that they’re now included in some of the Slender Man fan art and stories. What to make of that? I don’t know, and I don’t think the movie does either. Although this would seem to be directly relevant to the film’s theme, it shies away from analysing it, or indeed from examining the individuals or online communities fascinated with the Slender Man.

Beware the Slenderman is a very watchable documentary about a terrible crime committed by two girls against a third, the emotional effect that crime had on their parents, and how the Wisconsin justice system dealt with the attack. On that level, the film succeeds. When it attempts to find a greater meaning to the incident it fails, and I would say fails badly. It spends a considerable amount of time examining a fascinating congerie of urban legends related to the attack, but this body of lore built around the figure of the Slender Man finally feels like a blind alley, a diversion from the human issues related to the violence. If you want to see a documentary about the attack, or about a true criminal incident, it’s worthwhile. If your interest is in the phenomenon of the Slender Man, or about the causes of such extreme actions, it isn’t.

Next was In A Valley of Violence; a short named “Limbo” screened beforehand. “Limbo” is the story of a man stranded in a desert after leaving his old life, and the surprising choices he’s faced with. It’s a fantasy, but a highly ambiguous one. I felt it was a bit too ambiguous — the results of the lead character’s choice was unclear to me. I think it’s about someone being trapped in a behavioural loop, but I’m not sure. The dialogue’s sharp, the acting’s fine, the visuals evocative; but while I don’t necessarily want every loose end tied up in every story, in this case I felt more clarity would have helped the film.

In A Valley of Violence, on the other hand, was nothing but clear, and in the best way. Directed and written by Ti West, who is better known as a horror director, it stars Ethan Hawke as Paul, a drifter with a mysterious past; John Travolta as a marshal of the near–ghost town of Denton; James Ransone as the Marhal’s sadistic son, Gilly; Karen Gillan as Ellen, the son’s love interest; and Taissa Farmiga as Mary Anne, a young woman in Denton who desperately wants out. It looks as though she’ll be disappointed, as Hawke’s gunman passes swiftly through town after a quick fistfight with Gilly. But the marshal’s son can’t let things be and goes after Paul, prompting his return to Denton intent on gunplay.

In A Valley of Violence, on the other hand, was nothing but clear, and in the best way. Directed and written by Ti West, who is better known as a horror director, it stars Ethan Hawke as Paul, a drifter with a mysterious past; John Travolta as a marshal of the near–ghost town of Denton; James Ransone as the Marhal’s sadistic son, Gilly; Karen Gillan as Ellen, the son’s love interest; and Taissa Farmiga as Mary Anne, a young woman in Denton who desperately wants out. It looks as though she’ll be disappointed, as Hawke’s gunman passes swiftly through town after a quick fistfight with Gilly. But the marshal’s son can’t let things be and goes after Paul, prompting his return to Denton intent on gunplay.

The story is a simple but note-perfect Western, driven by revenge, with violence escalating and guns growing increasingly significant — there’s a steady escalation of force throughout, but never to ludicrous levels. It’s just right to bring out character, to show determination or cowardice or desperation or whatever else is at the core of a man’s soul (the women here aren’t exactly bystanders, but don’t have quite the same role in the confrontations). Which is to say it’s good genre drama, simplifying the essence of the characters in a way that makes for an action-filled and engaging story. Particularly notable are well-handled switches in perspective during the extended final confrontation, as we see Paul’s plans and the marshal’s frantic attempts to regain control of the situation.

Hawke’s performance here is very well-judged. His Paul is soft-spoken, often bewildered, and clearly damaged. The script gives us just enough of his past to have a sense of what’s going on with him, aided by a modern understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder. Travolta makes his sinister marshal all leatheriness and limping steps, tough and clever but increasingly aware he’s out of his depth. We understand who he is, if not why, and why Denton is the way it is, but also why Gilly is the way he is. The small network of characters act and react in ways that make sense. Gillan’s character is very reminiscent of her Amy Pond (Doctor Who), but meaner, more exhausted, more limited — all of which makes sense for a person in her situation in Denton.

West’s direction is sharp, finding interesting angles while also solidly establishing geography. You know where everything is in relation to everything else, not just in a given building but all throughout the town. Denton feels like a physical place, if a little like a Western theme park for the characters to run around in and shoot each other. On the other hand, the terrain outside the town is splendid to look at, capturing the natural beauty that often goes with the Western genre. And the pacing is perfect: tension builds during Paul’s first visit to Denton, then explodes in the second as West’s camera follows events nicely.

West’s direction is sharp, finding interesting angles while also solidly establishing geography. You know where everything is in relation to everything else, not just in a given building but all throughout the town. Denton feels like a physical place, if a little like a Western theme park for the characters to run around in and shoot each other. On the other hand, the terrain outside the town is splendid to look at, capturing the natural beauty that often goes with the Western genre. And the pacing is perfect: tension builds during Paul’s first visit to Denton, then explodes in the second as West’s camera follows events nicely.

It’s a well-told Western, down to the wonderful guitar soundtrack. The script’s lean, and the humour works, notably a priest (Born Gorman) bent on saving souls even though his own doesn’t seem in any too good a shape. The spiral of revenge and violence is credible and the scale is believable: Paul isn’t up against a private army, just a few men. If you wanted to criticise the film, there’s a valid argument that it doesn’t reinvent the wheel, and can feel at times a touch too generic. The characters are familiar from any number of other stories, and the bad guys even wear black.

But then again, the movie’s not trying to reinvent the wheel. It’s aiming at telling a Western and hitting the genre highlights by way of telling an engaging story. You can look at it as saying something about violence, and perhaps something about masculinity — again, good traditional Western themes. It feels like an attempt to use a few twenty-first century character ideas to reinvigorate a (primarily) twentieth century genre about the nineteenth century. However you define it, it’s engaging and entertaining, telling its tale and doing its job.

I headed across the street next to watch The Unseen. Before it began the audience was introduced to the writer and director, Geoff Redknap. Redknap has had a long career working in make-up and special effects, including Deadpool, Watchmen, and the X-Men movies, as well as The X-Files, The Flash, and other TV shows; and he spoke a bit about working his way up through short films before directing The Unseen, his first feature. He said we would be the first “real people” to watch it, and promised to return for a question-and-answer session afterward.

I headed across the street next to watch The Unseen. Before it began the audience was introduced to the writer and director, Geoff Redknap. Redknap has had a long career working in make-up and special effects, including Deadpool, Watchmen, and the X-Men movies, as well as The X-Files, The Flash, and other TV shows; and he spoke a bit about working his way up through short films before directing The Unseen, his first feature. He said we would be the first “real people” to watch it, and promised to return for a question-and-answer session afterward.

The movie follows Bob Langmore (Aden Young), a former NHL goon and now millworker in northern British Columbia. He’s suffering from a degenerative condition: bit by bit, he’s turning invisible. A lot of pain comes with the slow progress of his invisibility, but a certain toughness, also. Only something’s going on with his daughter Eva (Julia Sarah Stone), who lives with his divorced wife (Camille Sutherland) and her current wife in Vancouver. At Camille’s long-distance urging Bob decides to go to visit her — his condition was inherited from his father, and if it’s turned up in her, he’s the only one who can really talk to her about it. But to get to Vancouver Bob’s got to run an errand for a small-time criminal. Will Bob’s baggage drag down both him and his daughter?

Perhaps ironically, The Unseen is a beautiful movie to look at, especially the scenes in the north. You can see the cold, and smell the sawdust and oil of the mill. Long brooding takes with minimal dialogue and virtually no exposition encourage us to pay attention, to watch and think about what we see. Some of the shots, crucial character moments, are left unexplained until late in the film — and this works, drawing us in and rewarding our attention. It’d be for nothing if the images weren’t so memorable themselves, but there’s a constant sense of character here, even to the backgrounds.

Perhaps ironically, The Unseen is a beautiful movie to look at, especially the scenes in the north. You can see the cold, and smell the sawdust and oil of the mill. Long brooding takes with minimal dialogue and virtually no exposition encourage us to pay attention, to watch and think about what we see. Some of the shots, crucial character moments, are left unexplained until late in the film — and this works, drawing us in and rewarding our attention. It’d be for nothing if the images weren’t so memorable themselves, but there’s a constant sense of character here, even to the backgrounds.

The characters themselves shine, and Young’s Bob Langmore is stunning. His accent, his stance, his attitude — he’s a man who wants to fight but also wants to duck away from attention, and all through the film Young’s utterly absorbed in the character and his slow development. Stone’s Eva is also especially worthy of note, strong-willed but a little lost. The slow development of the relationship between the two of them, the daughter and the father who left her, is the heart of the film; and it feels true all along the line.

The story is effective, but Redknap seems to have chosen to focus on character above plot. Details about the invisibility disease are few and far between, with much left unexplained. One aspect of the criminal plot seems to peter out, while another, to do with human trafficking, comes in unexpectedly. It’s a little jarring, particularly the way Redknap edits the film. It works overall, allowing the characters to develop in the way they need to; and you could reasonably argue that this emphasises something human in the story, avoiding the contrivances of a machined setup-development-payoff action-story plot.

In fact, the story of the film is remarkably full — both small town and big city are well-established, and a subplot about strange events at a partially-abandoned medical facility gives a number of unexpected angles to the film. There’s a lot going on in this movie in terms of story, between various criminal gangs and the decaying hospital and Bob’s disease and Eva’s family. The balance between elements succeeds, creating if not an epic feel then at least a highly varied one. There seems bit of slackening of tension in the third act (which also puts Eva in danger one time too many), but at the same time it resolves everything that needs to be resolves and ends on a strong and genuinely touching note.

In fact, the story of the film is remarkably full — both small town and big city are well-established, and a subplot about strange events at a partially-abandoned medical facility gives a number of unexpected angles to the film. There’s a lot going on in this movie in terms of story, between various criminal gangs and the decaying hospital and Bob’s disease and Eva’s family. The balance between elements succeeds, creating if not an epic feel then at least a highly varied one. There seems bit of slackening of tension in the third act (which also puts Eva in danger one time too many), but at the same time it resolves everything that needs to be resolves and ends on a strong and genuinely touching note.

Tonally Bob’s world-weariness comes through perfectly, and while that sounds like it should make the movie feel downbeat it actually has the reverse effect. Bob’s wariness and combativeness create the sense for us of a world full of dangers and of a man facing them who we really can’t predict. Eva, her father’s daughter, is just as strong-willed and just as cynical, if younger and less experienced. Between them, they create a unique tone, even beside the fantasy of the story: a class-conscious realism, a family bond Bob struggles to keep apart from the seediness he’s drawn to by the life he chooses to lead.

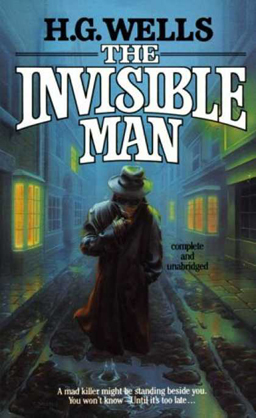

It’s worth noting that the invisibility theme is relatively minor. It shapes the story, but in unexpected ways. Up until the very end Bob’s never more than partially invisible, and clearly views his condition as curse, not super-power. This is nothing like H.G. Wells. Redknap imagines invisibility as a spreading skin condition, one that shows more and more of the bones and blood and organs and other viscera under the flesh. But for most of the movie, Bob hides that invisibility under bandages and long sleeves and whatever else he needs to. Redknap may have a background in make-up effects, but he knows the value of restraint.

It’s worth noting that the invisibility theme is relatively minor. It shapes the story, but in unexpected ways. Up until the very end Bob’s never more than partially invisible, and clearly views his condition as curse, not super-power. This is nothing like H.G. Wells. Redknap imagines invisibility as a spreading skin condition, one that shows more and more of the bones and blood and organs and other viscera under the flesh. But for most of the movie, Bob hides that invisibility under bandages and long sleeves and whatever else he needs to. Redknap may have a background in make-up effects, but he knows the value of restraint.

As strong as the direction in The Unseen is, though, what strikes me still most forcefully about the film is Young’s acting. There’s a point in some performances where an actor and character seem to possess each other, where impersonation ends and a person stands before you on film. That happens here. Young makes us want to watch the movie, makes us wonder what’s happened to him and who he is, and before long we’re sympathising with a none-too-bright self-destructive brawler. (I will add that one of the funniest moments of the film comes with a character note from Young, as Bob goes into a situation he knows is going to be a brawl — and throws down his gloves and takes off his jacket in moves familiar to anyone who’s ever watched a hockey fight begin.)

The Unseen is a thoughtful, involving story that means more than it says. It takes a new and interesting angle on the idea of invisibility, and builds a powerful film around some excellent performances. Occasional plot infelicities are more than made up for by well-developed characters. I was well pleased at having seen The Unseen.

After the screening Redknap returned for a question-and-answer session along with producer Katie Weekley and actress Camille Sullivan. According to my scribbled notes, Redknap was asked first about his restraint in using make-up and visual effects. He said that he’d received support in the short films he’d made when he embraced his background in effects, but that he didn’t want to make a feature that was wall-to-wall make-up, preferring a “less is more” approach. Added to that was an appreciation for how difficult it can be to create make-up effects that hold up over the course of a film.

Asked whether his personal background was reflected in the film, Redknap said that he was from northern BC and had worked in a sawmill for two years (he joked that he wasn’t turning invisible, but I did find myself wondering if the film could be read as being about the invisibility of people in remote small towns). Asked about the production, Weekley noted that it was supposed to have been a microbudget film, while Redknap described how the sawmill where he’d worked and in which they’d been planning to shoot actually shut down just before filming; as a result their plans to shoot in northern BC were scrapped and much of the film was shot in Kelowna, BC, after a friend of his in forestry recommended that he approach a family-owned mill for a location — big mills, Redknap observed, were reluctant to accept liability for the filming. He loved the place they ended up with, but did find it difficult on a practical level to film there because of a lack of space.

Asked whether his personal background was reflected in the film, Redknap said that he was from northern BC and had worked in a sawmill for two years (he joked that he wasn’t turning invisible, but I did find myself wondering if the film could be read as being about the invisibility of people in remote small towns). Asked about the production, Weekley noted that it was supposed to have been a microbudget film, while Redknap described how the sawmill where he’d worked and in which they’d been planning to shoot actually shut down just before filming; as a result their plans to shoot in northern BC were scrapped and much of the film was shot in Kelowna, BC, after a friend of his in forestry recommended that he approach a family-owned mill for a location — big mills, Redknap observed, were reluctant to accept liability for the filming. He loved the place they ended up with, but did find it difficult on a practical level to film there because of a lack of space.

Asked why he’d made a movie about an invisible man, Redknap said he’d asked himself “what have I not seen lately.” He realised he hadn’t seen a movie about invisibility since Hollow Man, in the year 2000. Then he decided to move away from the usual crutches for the story, and discard the idea of a mad scientist. Instead his main character would be a millworker, with no idea what was happening to him. He credited Weekley for the idea of progressive invisibility, and Weekley noted that the idea of partial invisibility made cinematic sense — why cast someone as your lead and then not show them?

Asked about Aden Young’s performance, Redknap said that Young was born in Ontario but had moved to Australia when young, so he’d had a noticeable accent that he changed for the role. Sullivan said he was a wonderful actor and very collaborative, that he spoke a lot with her between scenes about their characters’ intentions. Redknap added that Young disappeared into the role so completely he was shocked, after twenty-three days of shooting when Young was always Bob Langmore, to see him shaved and hear his real accent. Redknap called Young “scary,” but Sullivan said he was fun except on-camera.

An audience member asked about the details of the progressive invisibility, and Redknap confirmed that the idea (briefly touched on in dialogue) was that it was painful but made Langmore stronger and tougher. The movie was in some ways a hero’s origin story, with Langmore fighting his condition as far as he could before accepting it. A question about the music in the film led to Weekley discussing the process of finding bands, and how the score was done by Harlow MacFarlane, a friend of Redknap’s who writes ‘industrial ambient’ music; and that led to Redknap saying that there was an extended post-production and editing period for the movie, because it had been interrupted while he worked on Deadpool. He said he was glad of the break, as it allowed him to return to editing with fresh eyes.

An audience member asked about the details of the progressive invisibility, and Redknap confirmed that the idea (briefly touched on in dialogue) was that it was painful but made Langmore stronger and tougher. The movie was in some ways a hero’s origin story, with Langmore fighting his condition as far as he could before accepting it. A question about the music in the film led to Weekley discussing the process of finding bands, and how the score was done by Harlow MacFarlane, a friend of Redknap’s who writes ‘industrial ambient’ music; and that led to Redknap saying that there was an extended post-production and editing period for the movie, because it had been interrupted while he worked on Deadpool. He said he was glad of the break, as it allowed him to return to editing with fresh eyes.

Asked how much the movie changed from its first satisfactory edit to its final shape, Redknap said that it went through a lot of forms, many of which were two and a half hours long (the final version’s 104 minutes). The script was only 100 pages, but he ended up with a lot of film. Redknap observed that it’s never a bad thing to have too much story, as you can always pare it down and take out elements that don’t work. The movie, he acknowledged, is a slow burn; he sought advice in editing, and eventually realised firstly that he had to go with his gut, and secondly that the role of the director is to protect the film.

A question followed about a plot element in the film and whether, as the characters believed, it affected the progress of the invisibility; Redknap said he’d intentionally left it open, perhaps to explore in a sequel, but primarily to give them some kind of hope. A questioner then asked about an aspect of the crime plot, in which Bob had to bring a certain item to Vancouver; the questioner used to work in Vancouver, and said she’d seen similar smuggling go on. Redknap said that the plot had originally involved drug smuggling, but that it seemed to make more sense for the story in its current form. Someone asked what it was like working with bears (two bears turn up in the film at a couple of points); Weekley said they were cute, and their trainers very good; that the trick was to give them a small and apparently useless fence that served them as a visual marker, telling the bears that they were safe.

That ended the questions, and I left the theatre pondering the many things that go into making a movie. Overall that day I felt like I’d seen three different approaches to genre and storytelling. A documentary that was suspicious of horror stories; an almost classical Western; a story about an invisible man that didn’t fit neatly into any genre, and in fact that had come from a director asking himself what he hadn’t seen. It struck me, and still strikes me, as a good question for a storyteller to ask. At any rate, this year as in years previous I’d see a lot of movies at Fantasia that weren’t much like anything else I’d seen. I’d watch another two the very next day.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.