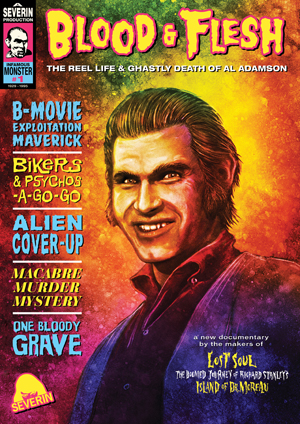

Fantasia 2019, Day 6, Part 2: Blood & Flesh — The Reel Life & Ghastly Death of Al Adamson and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein

I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death.

I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death.

(Before the documentary played, we saw “When Larry Met Stanley,” a six-minute short directed by Katy Jensen and Mike Leans. It features Larry Cohen, an independent B-movie director, recounting directly to the camera an anecdote about the time he met Stanley Kubrick, when Kubrick was just starting out as a director. It’s a cute story, and Cohen, who passed away earlier this year, tells it well.)

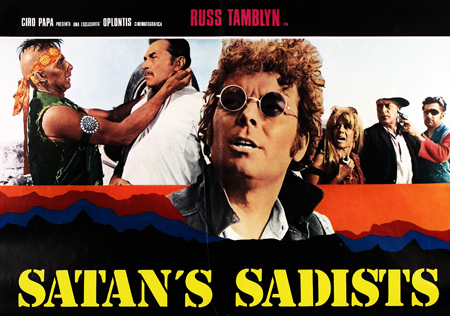

Blood & Flesh opens at the end, with Adamson’s murder. It then goes back to work its way back through Adamson’s life. He was the son of a B-movie actress and B-movie director, and got his start in film working with his father. He later teamed with producer Sam Sherman to set up Independent-International Pictures, turning out grindhouse schlock through the 60s and 70s, chasing whatever was in the zeitgeist — biker films like Satan’s Sadists, blaxploitation like Black Samurai, softcore sexploitation like Naughty Stewardesses.

He withdrew from film as the industry changed in the late 70s, emerging briefly to make never-released “documentaries” about alien visitations, which he apparently believed in. Then, in 1995, he went missing. His body was soon found. He had been murdered by his live-in handyman. The case was briefly a media sensation, apparently a case of life imitating art: the director of cheap horror films brutally killed.

Blood & Flesh tells this story mostly through interviewees speaking to camera. The selection of material seems strong, and is bolstered by other footage including an interview with Adamson from shortly before his death. The interviews give a full picture of the man’s life and career, and often play against each other to good effect, giving different perspectives on an incident or on some aspect of Adamson’s personality. Clips from Adamson’s movies are used well to further illustrate points.

The documentary does not shy away from discussing the quality of Adamson’s movies, which could charitably be described as ‘poor.’ Adamson’s own colleagues discuss his lack of talent. The point with these films, though, was not to be good. It was to make money, quickly, while spending as little as possible. In this, Adamson more or less succeeded.

The documentary does not shy away from discussing the quality of Adamson’s movies, which could charitably be described as ‘poor.’ Adamson’s own colleagues discuss his lack of talent. The point with these films, though, was not to be good. It was to make money, quickly, while spending as little as possible. In this, Adamson more or less succeeded.

He would shoot a film in a week or so. The movie might have as many as five different titles so it could be sold many times over, occasionally re-edited to add a sub-plot or some kind of new content to cash in on a current craze. For star power, he recruited fading old movie actors desperate for one last role — Aldo Ray, John Carradine, Lon Chaney Jr. His creations played drive-ins and grindhouses, and turned profits.

Sometimes the schemes to make a buck could get elaborate, if never costly. To publicise The Naughty Stewardesses, Sherman created a fake industry group, “Stewardesses For a Better Image,” and had them ‘protest’ the film in uniform. Newspapers fell for it. Another time, Adamson and Sherman bought a black-and-white Filipino horror film on the cheap, and Adamson shot scenes with American actors that introduced a sub-plot about ‘spectrum radiation.’ Adamson and Sherman then tinted the black-and-white scenes various colours with the in-story explanation that spectrum radiation was causing the weird monochrome imagery, and promoted the tinted film by calling it a new colour process called “Spectrum-X.” To top it off, they retitled the movie (originally Tagani) to Horror of the Blood Monsters.

And what’s oddest in retrospect is that the Adamson-directed scenes in Blood Monsters were shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, who only a few years later would win an Oscar for Best Cinematography for Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Stewardesses was shot by Gary Graver, who would go on to work with Orson Welles on F For Fake and The Other Side of the Wind. By this point, although Adamson and Sherman were paying little or nothing, they’d managed to attract some people willing to work with them as a way into the movie industry.

And what’s oddest in retrospect is that the Adamson-directed scenes in Blood Monsters were shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, who only a few years later would win an Oscar for Best Cinematography for Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Stewardesses was shot by Gary Graver, who would go on to work with Orson Welles on F For Fake and The Other Side of the Wind. By this point, although Adamson and Sherman were paying little or nothing, they’d managed to attract some people willing to work with them as a way into the movie industry.

As a result, Blood & Flesh has a subtle but noticeable shift in tone over its first two acts. At first it’s dominated by nostalgia, as Sherman, still dedicated to Adamson’s memory, recalls their early days affectionately. Then a lot of their collaborators from the 60s weigh in, with more exasperation. As old or older than Adamson and Sherman, they recall the lack of funding bitterly even as they tell weird stories about shooting in the Spahn Ranch, at the time the home of a bunch of hippies led by one Charles Manson. (True to form, after the Sharon Tate murder the ad campaign for Satan’s Sadists boasted “Hippie Psychos On A Mad Murder Spree! Filmed On The Actual Locations Where The Tate Murder Suspects Lived Their Wild Experiences!”)

But then as the 70s go on, younger filmmakers began to work for Adamson and Sherman, and a lot of them look back on those days with real warmth. They were in a different position in life, and perhaps wanted something different — experience, an entrée into the industry. Unsurprisingly they looked at things differently than the older crew.

But then as the 70s go on, younger filmmakers began to work for Adamson and Sherman, and a lot of them look back on those days with real warmth. They were in a different position in life, and perhaps wanted something different — experience, an entrée into the industry. Unsurprisingly they looked at things differently than the older crew.

At any rate, the drive-ins that bought Adamson’s pictures didn’t last much longer. The last third of the film is therefore concerned with the details of Adamson’s death. It’s an odd shift into the true-crime genre. It’s well done, bringing in a host of interviews, even an audio phone call with the handyman convicted of killing Adamson (he says he didn’t do it). And yet it’s less interesting, because it’s open-and-shut in a way the sections about filmmaking aren’t. In the parts of the documentary about film you don’t really know what’s coming next. In the section on Adamson’s death, you largely do. While a good work of investigation and editing, it doesn’t feel as though it’s an entirely logical outgrowth of the rest of the film.

Which in a very real way speaks to the success of Blood & Flesh. It finds what’s most interesting in movies that are not especially interesting, or indeed good. It opens a window into a particular way of making films, and into a particular part of the American film industry. The strength of the movie is its depiction of this unpromising filmmaking scene, and of idiosyncratic talents like Gary Graver. It’s a little window onto a time now gone and onto a junk-culture level of cinema that may never have produced good films but did produce the occasional interesting filmmaker who went on to better things. Perhaps in a sense the true-crime aspect is the best way to end the movie, an exclamation point on the end of an era, definitively marking a change in the selling of film.

After Blood & Flesh ended, director David Gregory and several of his collaborators took questions. Asked if it was a complicated process to make the film, Gregory said getting interviews from Adamson’s collaborators was the easy part. It got a little complicated to do the true-crime section of the film; some of the cops had retired, and it was difficult to find Adamson’s housekeeper (who had a lot to say, in the end). Producer Heather Buckley hired a private investigator, and got footage from the police as the Adamson case had happened to take place during a window when they routinely filmed visits to crime scenes. Buckley observed that the small town of Indio, California, was not used to exhumation requests and people asking for police footage. In the end they got the footage by promising to upgrade the police department’s videotape archives to digital copies.

After Blood & Flesh ended, director David Gregory and several of his collaborators took questions. Asked if it was a complicated process to make the film, Gregory said getting interviews from Adamson’s collaborators was the easy part. It got a little complicated to do the true-crime section of the film; some of the cops had retired, and it was difficult to find Adamson’s housekeeper (who had a lot to say, in the end). Producer Heather Buckley hired a private investigator, and got footage from the police as the Adamson case had happened to take place during a window when they routinely filmed visits to crime scenes. Buckley observed that the small town of Indio, California, was not used to exhumation requests and people asking for police footage. In the end they got the footage by promising to upgrade the police department’s videotape archives to digital copies.

Gregory recalled speaking to Adamson’s convicted killer, Fred Fulford, who had offered no defense at his trial but who’d had 25 years since to come up with excuses for his actions. Gregory noted that since you could not film in a California prison, they could only use the audio from the phone call. Early cuts didn’t even use that, since Gregory found there was little of interest in the 1.5 hour conversation; Fulford didn’t understand many of the questions, and offered only a repetitive insistence that he hadn’t committed the crime. Fulford’s in prison for life, said Gregory, and every time he comes up for parole Adamson’s second wife attends the hearing to speak against him.

Asked about footage of Adamson used in the film, Gregory said it came from a student film with a career retrospective interview of Adamson just a few months before his death. There was little other footage of Adamson, who had not done a lot of personal PR. Gregory also noted that he had a poor-quality interview with Regina Carrol, Adamson’s first wife, who appeared in many of his movies; he said it would be an extra on a DVD or Blu-ray release.

In response to another question, he described a filmmaker’s nightmare when interview footage was lost, some of which had been quite emotional. The interviewees agreed to sit down with the filmmakers again, and their second interviews were much better — they’d had time to think about their answers. Asked whether an interview in the film was the last ever recorded with Vilmos Zsigmund (who died early in 2016), Gregory said he believed it was; the interview had actually been about Heaven’s Gate, but he’d added a few questions about Adamson at the end. Asked about a quick transition from Adamson shooting his last documentaries to Fulford entering his life, Gregory said that was the way it had happened in reality — there was a matter of only a few days between Adamson ending work and then meeting Fulford.

In response to another question, he described a filmmaker’s nightmare when interview footage was lost, some of which had been quite emotional. The interviewees agreed to sit down with the filmmakers again, and their second interviews were much better — they’d had time to think about their answers. Asked whether an interview in the film was the last ever recorded with Vilmos Zsigmund (who died early in 2016), Gregory said he believed it was; the interview had actually been about Heaven’s Gate, but he’d added a few questions about Adamson at the end. Asked about a quick transition from Adamson shooting his last documentaries to Fulford entering his life, Gregory said that was the way it had happened in reality — there was a matter of only a few days between Adamson ending work and then meeting Fulford.

Asked about the structure of the film, Gregory said it was hard to set up, and hard to choose what to focus on — production stories or true crime. He decided to start with the crime material then move to talking about the films, as other tellings of Adamson’s story don’t focus on his work. Asked if it was difficult for Adamson’s friend Sam Sherman to talk about him, Gregory said no, Sherman had talked about Adamson’s death a lot over the years. He coped by going into promoter mode, distancing himself from it by treating it like a sensationalist story. Asked how many hours of footage had gone into the film, Gregory said there were 29 features, the same number of interviews (each at least two hours long), and archival TV news and police footage.

Asked about the material with Manson, Gregory said he was surprised by it, and noted some elements of Satan’s Sadists that he thought might have inspired Manson. Asked about the use of old Hollywood actors, Gregory said it didn’t bother Adamson if the actors were in wheelchairs or in grave health. To another question Gregory said he’d had to stop going film by film through Adamson’s career as his material in the 70s was more competent and the stories less interesting; but then the people working with him were more positive about him. Asked if he would have done a version without the crime story, Gregory said no, it was always going to be part of the film, and in fact was two-thirds of the first cut of the film.

Asked if he’d learned anything that was weirder than he’d expected, Gregory said yes, the material around Adamson’s last documentary, on the subject of aliens. He noted that when he’d interviewed Adamson’s second wife, and heard her strange stories about the films, he knew he had a documentary. Asked if he’d been able to see footage of the alien film, he said yes, Adamson’s housekeeper had a VHS tape with 25 minutes from when Abramson had tried to explain to her what he did.

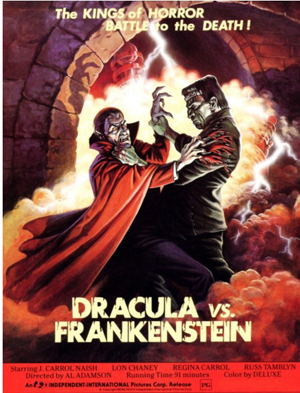

That ended the questions, and a surprise followed, which had actually been announced on the Fantasia web site but not in the print version of the program: the world premiere of Severin Films’ new restoration of Al Adamson’s 1971 epic Dracula Vs. Frankenstein. I hadn’t expected it, but by that time it was well past 11 PM and I had nowhere else to be. I sat back, and pretended I was in a midnight showing in an old-fashioned grindhouse.

That ended the questions, and a surprise followed, which had actually been announced on the Fantasia web site but not in the print version of the program: the world premiere of Severin Films’ new restoration of Al Adamson’s 1971 epic Dracula Vs. Frankenstein. I hadn’t expected it, but by that time it was well past 11 PM and I had nowhere else to be. I sat back, and pretended I was in a midnight showing in an old-fashioned grindhouse.

Dracula Vs. Frankenstein had come up a few times in Blood & Flesh. It had started out as a sequel to Satan’s Slaves, in which Russ Tamblyn played the vicious head of a biker gang. As horror became more popular, Adamson decided to add some scenes to the film to turn it into a horror film. The story that he’d already shot involved a young couple investigating a strange haunted-house fairground attraction on a California beach, which was overseen by a wheelchair-bound scientist (J. Carrol Naish) named Dr. Durea. But at some point one of the other characters refers to him as “Doctor Durea — if that is his real name.” Noticing this, Adamson decided Durea’s real name could be Frankenstein, and who would track him down but Count Dracula?

It’s a cute idea, but of course it doesn’t do anything for the movie, which becomes completely incoherent. Tamblyn’s bikers appear and disappear at random. The plot with the young couple doesn’t mesh well with the machinations of Count Dracula. It’s generally a mishmash, and that’s being generous.

It’s hard to know where to start in describing the movie. Let me say this: the restoration looks nice. The colours pop, and it’s surprisingly pretty to look at (Gary Graver handled some of the cinematography). After that …

Lon Chaney, Jr. plays the doctor’s assistant. Tragically, he was dying of cancer at the time, and was unable to speak. Naish had false teeth constantly clicking against each other, audible on the soundtrack. He also couldn’t remember his lines, so crew members held up cue cards for him to read from. This worked, but he also had a glass eye, meaning that during close-ups his living eye would be flicking back and forth scanning the cue card while the glass eye stayed still.

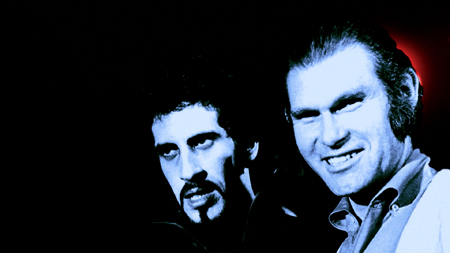

Then there’s Zandor Vorkov (real name: Roger Engel), often hailed as the worst Dracula in cinema history. He was a stockbroker for Sherman and Adamson, who Adamson thought would make a good vampire. Forrest J. Ackerman, who had a bit part in the film, came up with his stage name, based vaguely on Boris Karloff and Anton Szandor LaVey. He’s not good. But then nothing in the film’s really what you could call good.

Then there’s Zandor Vorkov (real name: Roger Engel), often hailed as the worst Dracula in cinema history. He was a stockbroker for Sherman and Adamson, who Adamson thought would make a good vampire. Forrest J. Ackerman, who had a bit part in the film, came up with his stage name, based vaguely on Boris Karloff and Anton Szandor LaVey. He’s not good. But then nothing in the film’s really what you could call good.

Especially the dialogue. Dracula ambushes Ackerman’s character at his car, and orders him to drive him to meet Frankenstein. When Ackerman’s character asks who he is, Dracula utters the immortal line: “I am known as the Count of Darkness, the Lord of the Manor of Carpathia. Turn here.” The lack of emotion with which Vorkov delivers the dialogue completely fails to sell it. An evil dwarf urges other characters: “You must open your eyes to see things!” A police sergeant grimly reflects that “It seems that living near the water brings out the best and worst in us.” I still don’t know what he means, but later he warns the leading lady: “If you’ve got a fireplace, burn some wood in it. It’ll be a lot better than running loose on the streets.”

Regina Carrol is that leading lady, and she seems to be taking things seriously. You almost can’t help but root for her. Russ Tamblyn knows what’s going on, making his sleazy biker Rico entertaining. Most other actors fall between the two.

It’s difficult to write much about this film, because it was barely intended as a “film” in the way most films are. That is, the approach to story is beyond mercenary. The thing exists to make money; something vaguely like a coherent story helps to make money; so there’s something vaguely like a coherent story here. Mainly it’s an excuse to put two well-known characters together in a single exploitation film, and come up with a thrilling poster. I suppose on that level it works.

It’s difficult to write much about this film, because it was barely intended as a “film” in the way most films are. That is, the approach to story is beyond mercenary. The thing exists to make money; something vaguely like a coherent story helps to make money; so there’s something vaguely like a coherent story here. Mainly it’s an excuse to put two well-known characters together in a single exploitation film, and come up with a thrilling poster. I suppose on that level it works.

And I have to say that watching it spool out over 91 minutes (it knows not to overstay its welcome, at least) I couldn’t say it wasn’t fun. I found myself wondering whether this is in fact the best film I’ve seen featuring a famous bat-themed character fighting against an equally famous character with superhuman strength; I think it’s at least the most entertaining. It’s a joke of a film, but everybody’s in on the joke, both the audience and the filmmakers. It is less a movie than the illusion of a movie. But then, in the words of Doctor Durea, AKA Frankenstein: “All illusions look real or they wouldn’t be illusions, would they?”

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I vividly remember the Dracula vs. Frankenstein layout in famous Monsters. Because he was in it, Forry Ackerman gave it a big boost.

I bet that was an interesting article. It must have been tricky to make this one look good!

Well, FM wasn’t exactly known for Pulitzer Prize journalism. The piece was mostly photos; I remember looking at a picture of Zandor Vorkov chomping Forry and thinking, “This is definitely not your typical Dracula!”