Fantasia 2019, Day 12, Part 1: Fly Me to the Saitama

On Monday, July 22, I was back at the Hall Theatre for one of the movies I was most anticipating. It was a new live-action manga adaptation from Hideki Takeuchi, director of the Thermae Romae films: Fly Me to the Saitama (Tonde Saitama, 翔んで埼玉). The script by Yuichi Tokunaga adapts the comics from the early 80s by Mineo Maya, although apparently the filmmakers had to finish the last two-thirds of the story for themselves.

On Monday, July 22, I was back at the Hall Theatre for one of the movies I was most anticipating. It was a new live-action manga adaptation from Hideki Takeuchi, director of the Thermae Romae films: Fly Me to the Saitama (Tonde Saitama, 翔んで埼玉). The script by Yuichi Tokunaga adapts the comics from the early 80s by Mineo Maya, although apparently the filmmakers had to finish the last two-thirds of the story for themselves.

The film tells a story inside a story. In the frame tale, a family drives from Saitama, a prefecture on the outskirts of Tokyo, to a party in the heart of Japan’s capital where the daughter is to be engaged. On the way, the radio tells a peculiar story about a fabled time when the people of Saitama were oppressed by their metropolitan overlords in Tokyo. They had to obtain special visas to enter; armoured police used facial-recognition technology to pick out any residents of Saitama who snuck through the massive border fences. The good folk of Saitama were second-class citizens at best, exploited labour for the greatness and glory of the glittering city of Tokyo. In this dystopia Momomi (Fumi Nikaido, Inuyashiki), son of the governor of Tokyo, is president of the student body of an elite academy; enter new student Rei Asami (Gackt), just back from studying in America. Momomi falls for the charismatic Rei, but Rei’s hiding a dark secret: he’s actually from Saitama, and is plotting the downfall of Tokyo. This is exposed surprisingly early, setting Rei and Momomi off on a journey that might change the world.

A couple quick notes about the actors mentioned above. First, Gackt is the professional name of a singer who the IMDB assures me is “the most successful male soloist in Japanese music history.” He’s in his 40s, and playing a teenager. Fumi Nikaido is a woman playing a male role; the manga was a boys’ love story, and the movie does faithfully (if briefly) refer to Momomi as male, and keep him in male dress. I have no idea how this plays out in the context of Japanese gender roles, but the point I want to get at is that you don’t wonder about either this or Rei’s age, because this movie gives every impression of being completely, utterly, joyfully uninterested in any of these details. The actors act, as theatrically as possible, and they are committed to their roles, and nobody mentions age or gender, and so we are pulled along into the berserk strangeness that is the story.

My last screening of July 21 brought me back to the De Sève Theatre for a showcase of animated short genre films from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, a grouping titled “Things That Go Bump In the East.” 11 films in a range of visual styles promised variety. I’d been having good luck with short films at the festival so far, and settled in eager to see what would come now.

My last screening of July 21 brought me back to the De Sève Theatre for a showcase of animated short genre films from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, a grouping titled “Things That Go Bump In the East.” 11 films in a range of visual styles promised variety. I’d been having good luck with short films at the festival so far, and settled in eager to see what would come now.

For my third movie of July 21 I wandered back to the Fantasia screening room. There, I settled in with a movie from the Philippines: Ode To Nothing. Written and directed by Dwein Ruedas Baltazar, it follows Sonya (Marietta Subong), a woman no longer young who owns her own funeral home in an unnamed town. Alone except for her father, Rudy (Joonee Gamboa), Sonya tries to keep the funeral home going despite debts to local loan shark Theodore (Dido Dela Paz). Then a body is brought to her for burial under suspicious circumstances. Rather than bury the corpse, though, Sonya begins to speak to it, and comes to think that the body of the old woman is bringing her luck — even to treat the body as her surrogate mother. Is the corpse responsible for the sudden influx of business to the funeral home? And even if it is, can you trust the gifts of the dead?

For my third movie of July 21 I wandered back to the Fantasia screening room. There, I settled in with a movie from the Philippines: Ode To Nothing. Written and directed by Dwein Ruedas Baltazar, it follows Sonya (Marietta Subong), a woman no longer young who owns her own funeral home in an unnamed town. Alone except for her father, Rudy (Joonee Gamboa), Sonya tries to keep the funeral home going despite debts to local loan shark Theodore (Dido Dela Paz). Then a body is brought to her for burial under suspicious circumstances. Rather than bury the corpse, though, Sonya begins to speak to it, and comes to think that the body of the old woman is bringing her luck — even to treat the body as her surrogate mother. Is the corpse responsible for the sudden influx of business to the funeral home? And even if it is, can you trust the gifts of the dead?

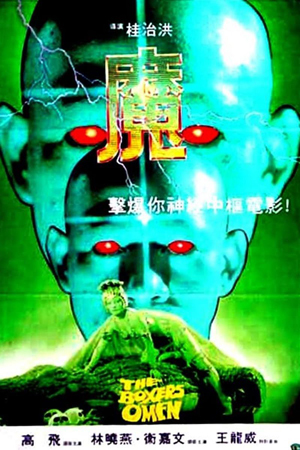

For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen

For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen