Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 8: Buddha’s Palm, Ojuju, The Reflecting Skin, and Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory

I was at Concordia’s De Sève Theatre early on Tuesday, July 21, for a showing of a 35mm print of the Shaw Brothers’ wuxia fantasy Buddha’s Palm. After that, I had a decision to make. At 5:30 the Nigerian zombie movie Ojuju played directly against a re-release of the British-Canadian horror-suspense movie The Reflecting Skin. Which would I see? And then after that, the first live-action film by director Mamoru Oshii, Nowhere Girl, was directly opposite a quirky romantic fantasy comedy, Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory. Again: which to see?

I was at Concordia’s De Sève Theatre early on Tuesday, July 21, for a showing of a 35mm print of the Shaw Brothers’ wuxia fantasy Buddha’s Palm. After that, I had a decision to make. At 5:30 the Nigerian zombie movie Ojuju played directly against a re-release of the British-Canadian horror-suspense movie The Reflecting Skin. Which would I see? And then after that, the first live-action film by director Mamoru Oshii, Nowhere Girl, was directly opposite a quirky romantic fantasy comedy, Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory. Again: which to see?

I’d have enough time after Buddha’s Palm to see one movie in the Fantasia screening room, and I decided I’d watch Ojuju there. The Reflecting Skin wasn’t available in the screening room, and anyway part of the draw of it was the chance to see a high-quality (2K) restoration of the movie for its twenty-fifth anniversary. As for the second decision, at the start of the day I assumed I’d go see Nowhere Girl. But sitting waiting for Buddha’s Palm, I changed my mind. Haruko seemed more overtly fantastic. And Nowhere Girl was in the screening room, so I’d have the chance to see it there — if I could find the time over the next few days among all the other movies I hoped to see.

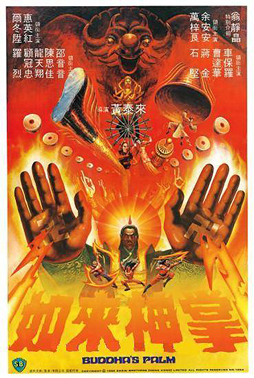

The screening of Buddha’s Palm was introduced by King-Wei Chu, one of the festival’s Directors of Asian Programming. He noted the rarity of 35mm prints of this film, and said “As long as I’m alive, Fantasia will play 35 millimeter,” adding: “The doctors say six months.” As he went on to explain, in 1982, when Buddha’s Palm was made, the popularity of kung-fu films was declining in the face of a craze for Star Wars-esque science fiction, “so [the Shaw Brothers] decided to introduce special effects.” He noted that the movie predated Tsui Hark and Zu Warriors From The Magic Mountain (Shu Shan – Xin Shu shan jian ke), itself an important fantasy wuxia film. That said, we got to see a trailer for another Shaw Brothers film, The Kid With the Golden Arm (Jin bei tong), and then the main feature began.

It wasn’t too dissimilar from Demon of the Lute, which I saw at Fantasia last year. The same sort of frenetic fight scenes, the same over-the-top use of sound effects, slow motion, and anything else that could enhance the melodrama and action. The story was relatively restrained, with slightly fewer factions, but still took sufficiently intricate twists to set up a range of fights. A martial arts master, Ku Han-Hun (Alex Man), with the power of the deadly Buddha’s Palm technique, goes into seclusion after a fight with four of his rivals; twenty years later, young Lung Chien-Fei (Tung-Shing Lee) is thrown off the side of a mountain by his enemy Auyang Hao (Kuan-Chung Ku) into deep mists, where a dragonlike dog or doglike dragon saves him and takes him to Ku Han-Hun. This launches a fantasy story of swordplay, martial arts, and special effects.

It wasn’t too dissimilar from Demon of the Lute, which I saw at Fantasia last year. The same sort of frenetic fight scenes, the same over-the-top use of sound effects, slow motion, and anything else that could enhance the melodrama and action. The story was relatively restrained, with slightly fewer factions, but still took sufficiently intricate twists to set up a range of fights. A martial arts master, Ku Han-Hun (Alex Man), with the power of the deadly Buddha’s Palm technique, goes into seclusion after a fight with four of his rivals; twenty years later, young Lung Chien-Fei (Tung-Shing Lee) is thrown off the side of a mountain by his enemy Auyang Hao (Kuan-Chung Ku) into deep mists, where a dragonlike dog or doglike dragon saves him and takes him to Ku Han-Hun. This launches a fantasy story of swordplay, martial arts, and special effects.

Buddha’s Palm (originally Ru lai shen zhang) was directed by Taylor Wong; the IMDB credits Suet-Fong Sui as writer and gives credits as well to On Szeto’s original screenplay and to Manfred and Taylor Wong for a revised screenplay. It’s fast and inventive. The humour’s obvious, but plays well. It’s the sort of movie that knows exactly what it is, joking about the conventions of “swordplay dramas” and rushing from fight scene to fight scene.

The special effects are comparatively restrained. With the Star Wars influence pointed out it’s fairly obvious, but I don’t know that I’d have noticed it otherwise. The effects are used to enhance a kung-fu fantasy rather than create something entirely different; there aren’t any science-fiction trappings here. Instead the effects illustrate the spiritual power of advanced martial arts techniques, with animated flaming swastikas bursting across the screen.

It should be noted that this movie’s more sexist than Demon of the Lute; for unexplained reasons, a woman can only master four of the eight moves needed to use the Buddha’s Palm technique. And with fewer moving parts to the plot, there are fewer action figures to fight each other. But the overall effect’s much the same. It’s a fizzy, impossible brew of action and tongue-in-cheek violence. W.H. Auden once said, in an essay about Byron’s mock-epic Don Juan, that there are certain works we don’t feel like reading often but which, when we’re in the mood, have absolutely no substitute. That about covers this movie, which goes to show that from the sublime to the ridiculous is only a single step.

It should be noted that this movie’s more sexist than Demon of the Lute; for unexplained reasons, a woman can only master four of the eight moves needed to use the Buddha’s Palm technique. And with fewer moving parts to the plot, there are fewer action figures to fight each other. But the overall effect’s much the same. It’s a fizzy, impossible brew of action and tongue-in-cheek violence. W.H. Auden once said, in an essay about Byron’s mock-epic Don Juan, that there are certain works we don’t feel like reading often but which, when we’re in the mood, have absolutely no substitute. That about covers this movie, which goes to show that from the sublime to the ridiculous is only a single step.

From the De Sève I headed to the screening room to watch Nigerian writer-director C.J. “Fiery” Obasi’s zombie movie Ojuju. I saw it through a Vimeo link, which was watermarked along the top and was also relatively heavily compressed. As a result, I can’t say too much about the visuals, beyond the fact that there seemed to be some interesting compositions and a strong colour sense.

After a piece of text telling us that 70 million Nigerians have no access to safe drinking water, we open with two men chatting. A third man stumbles toward them. They think he’s drunk. He isn’t. Undead violence ensues. From there we move to the main characters — a young man named Romero (Gabriel Afolayan); two women he’s involved with, Aisha (Yvonne Enakhena) and Alero (Meg Otanwa); Romero’s friend Emeka (Kelechi Udegbe); and Alero’s sister Peju (Omowunmi Dada). They live in a slum neighbourhood which is about to become infected by a rapidly-spreading plague, as one by one the inhabitants become zombies — or, as they say in this movie, ojuju.

After a piece of text telling us that 70 million Nigerians have no access to safe drinking water, we open with two men chatting. A third man stumbles toward them. They think he’s drunk. He isn’t. Undead violence ensues. From there we move to the main characters — a young man named Romero (Gabriel Afolayan); two women he’s involved with, Aisha (Yvonne Enakhena) and Alero (Meg Otanwa); Romero’s friend Emeka (Kelechi Udegbe); and Alero’s sister Peju (Omowunmi Dada). They live in a slum neighbourhood which is about to become infected by a rapidly-spreading plague, as one by one the inhabitants become zombies — or, as they say in this movie, ojuju.

It’s a deliberately-paced film. After the opening ojuju attack, it’s about a half hour before violence erupts again. Much of that time is spent in developing the characters and neighbourhood; it’s quite effective, convincingly making the case for the people we watch as being something other than undead prey. At the same time, we can see what’s happening, can see the slow spread of the disease almost in the background as genre elements begin to slip into place. By the time the horror of the film really kicks in, it’s been earned.

A large part of that is the way the film has the characters respond to the ojuju as living people who happen to be sick. They don’t at once think of ‘zombies’ or ‘the living dead,’ and why should they? As far as they’re concerned, they’re dealing with family and friends and neighbours who’ve gone out of their head due to a fast-spreading illness. They may be right. There’s no explicit statement made in the film about what happened to them. They move slowly, but don’t need to be killed with a head-shot, nor do they have any other typical zombie attribute — beyond their hunger for the living, and the way that hunger spreads.

Cleverly, once the surviving (in some cases “temporarily surviving”) characters realise what sort of danger they’re in, a sense of unreality sets in. They start to feel like they’re in a movie. That works because it comes off as more than a wink or a metafictional game; it has a sense of the sort of incipient disconnection from reality that comes from people trying to process emotional trauma. Which is further brought out by the fact that for all the talk about movies, nobody comments on Romero’s name.

Cleverly, once the surviving (in some cases “temporarily surviving”) characters realise what sort of danger they’re in, a sense of unreality sets in. They start to feel like they’re in a movie. That works because it comes off as more than a wink or a metafictional game; it has a sense of the sort of incipient disconnection from reality that comes from people trying to process emotional trauma. Which is further brought out by the fact that for all the talk about movies, nobody comments on Romero’s name.

Once the threat of the ojuju becomes clear, the suspense deepens into true horror. There’s violence, yes, but also atmosphere. The pace picks up slightly, but on the whole remains ominous rather than thrilling. The editing seemed to emphasise the deliberate pacing, sometimes too much so for my taste — there’s an extended sequence of one of the afflicted breaking down a door with no real dramatic tension. Overall, though, the movie’s pace brings out the building desperation of the characters, the way they have to think about improvising weapons and finding shelter in ways they’ve never had to before.

The pacing also I think encourages us to see the neighbourhood as a place and as a community. We’re following individuals struggling to survive, but we’re also seeing the collapse of a community — the poisoning of a group of people. The characters we follow aren’t always admirable, and indeed the film has no qualms about presenting Romero’s unsympathetic side as a slacker Lothario. But the problems they collectively face bring out their basic traits, for better or worse. And the end of the film it’s clear that the problems of one community can’t be isolated, can’t be seen apart from a larger context, and — of course — can’t be expected not to spread.

The pacing also I think encourages us to see the neighbourhood as a place and as a community. We’re following individuals struggling to survive, but we’re also seeing the collapse of a community — the poisoning of a group of people. The characters we follow aren’t always admirable, and indeed the film has no qualms about presenting Romero’s unsympathetic side as a slacker Lothario. But the problems they collectively face bring out their basic traits, for better or worse. And the end of the film it’s clear that the problems of one community can’t be isolated, can’t be seen apart from a larger context, and — of course — can’t be expected not to spread.

There’s a level on which Ojuju works as a standard zombie movie (or at least what I, no zombie movie expert, think of as a standard zombie movie). A social problem is identified; the problem causes people to die and become slow-moving corpses determined to feast upon the living; a small group of survivors struggle to stay alive as things go to hell around them. On that level it works perfectly well. You get involved with the characters, you care about what happens to them, you want to see what happens next. The issue of tainted drinking water isn’t made explicit in the story of the film beyond some frantic speculation by the characters, but lingering shots on dirty water bring the point home. The brief comparison we get with the city centre — all highways and office buildings — brings home the scale of social inequality.

The writing, moving through three languages (Yoruba, Igbo, and at least one Nigerian form of English), is tight and effective. Afolayan makes a charismatic lead, drawing us along as the horror mounts. But I thought the violence and action scenes were actually the weakest part of the movie: the fights often seemed overplayed and unconvincing, while the sound effects were too obvious. The film has an energy nevertheless. The point isn’t slickness, but rising tension. Ojuju imagines a situation that deepens and worsens and pulls us in to the horror. In that, the film’s quite effective.

The writing, moving through three languages (Yoruba, Igbo, and at least one Nigerian form of English), is tight and effective. Afolayan makes a charismatic lead, drawing us along as the horror mounts. But I thought the violence and action scenes were actually the weakest part of the movie: the fights often seemed overplayed and unconvincing, while the sound effects were too obvious. The film has an energy nevertheless. The point isn’t slickness, but rising tension. Ojuju imagines a situation that deepens and worsens and pulls us in to the horror. In that, the film’s quite effective.

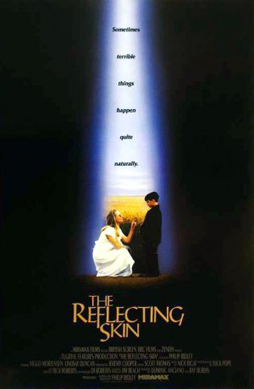

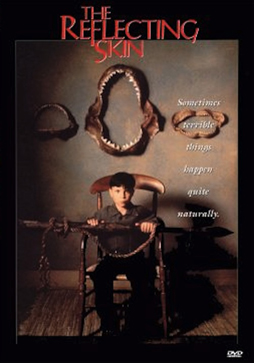

I left the screening room and headed up the street to the Hall Theatre for The Reflecting Skin wondering if I’d made a mistake. It would’ve been interesting to see Ojuju on the big screen. But, as it turned out, The Reflecting Skin delivered an excellent cinematic experience on its own terms. I don’t know whether I made the right call, but I can’t say I regret my choice to experience it in the theatre.

Originally released in 1990, the film’s been restored for its twenty-fifth anniversary. The story of a young boy in Idaho in about 1950, it’s full of wondrous shots of golden fields and big blue skies, long roads and high houses. The colours are spectacular, and the compositions so powerful every frame could have been released as a still: the visuals have a kind of fiery beauty, a sense of life and perfection.

Originally released in 1990, the film’s been restored for its twenty-fifth anniversary. The story of a young boy in Idaho in about 1950, it’s full of wondrous shots of golden fields and big blue skies, long roads and high houses. The colours are spectacular, and the compositions so powerful every frame could have been released as a still: the visuals have a kind of fiery beauty, a sense of life and perfection.

Written and directed by Philip Ridley, the film follows young Seth Dove (Jeremy Cooper). Seth’s expecting his brother back from the army, and passes his time with his friends playing sadistic jokes on a local woman named Dolphin Blue (Lindsay Duncan), a war bride whose husband died tragically. The movie opens with Seth and his friends inflating a frog, then exploding it as Dolphin passes by. It’s a macabre set-piece that sets up Seth, and establishes a sort of twisted view of boyhood the film will explore.

I’ve seen the movie compared to the work of David Lynch, and I can understand why. There’s a technical precision to it, to the images and the sounds and how they marry, that recalls Lynch — and the soundtrack to this film may be the lushest of any film I’ve seen at Fantasia. But there’s a different quality to Ridley’s vision, less whimsical and bizarre, more bleak and cynical. There are hints of the supernatural in Seth’s imagination, but none of them come to anything. Even horror, in this movie, is a kind of escapism.

We see Seth try to impose a childish understanding of the world on the things around him; after borrowing a pulp magazine from his father, he becomes convinced that Dolphin’s a vampire. Things grow worse at the return of his brother Cameron (Viggo Mortenson, and Mortenson’s resemblance here to Kyle MacLachlan circa 1990 surely helped foster the Lynch comparisons) — who begins a romance with Dolphin. More worrying are a group of greasers prowling about in a black studebaker. And among these different stories, Seth’s friends begin to die.

We see Seth try to impose a childish understanding of the world on the things around him; after borrowing a pulp magazine from his father, he becomes convinced that Dolphin’s a vampire. Things grow worse at the return of his brother Cameron (Viggo Mortenson, and Mortenson’s resemblance here to Kyle MacLachlan circa 1990 surely helped foster the Lynch comparisons) — who begins a romance with Dolphin. More worrying are a group of greasers prowling about in a black studebaker. And among these different stories, Seth’s friends begin to die.

All this, and I haven’t yet touched on the tension between Seth’s mother Ruth (Sheila Moore) and father Luke (Duncan Fraser). Luke has a past, one that’s led him to his small-town life where he runs a gas station and — as Seth’s mother establishes in a wonderful and vicious monologue early on — sweats gasoline. It sets up a red herring for the mystery of the boys’ death, and also, perhaps primarily, advances a discussion in the movie about masculinity.

This is a film with a lot on its mind, and if it’s easy to read as a black coming-of-age story for a boy over his head, it’s also easy to see it interrogating what it means to be a man. Cam, who becomes Seth’s role model later in the film, is an ambiguous figure; he’s left the army, and rejects an American flag when it’s brought to him, but has contempt for his father who let himself be “drained” by his mother. Ruth Dove becomes increasingly marginalised as Cam becomes a more prominent figure in the film, but Cam himself isn’t entirely healthy, and it’s easy for a modern audience to see that the wasting disease that afflicts him likely has its origin in the big bombs he saw being tested in the South Pacific.

Then again, the mention of Luke Dove being “drained” also returns us to Seth’s fantasies about vampires — particularly since he got the pulp story that inspired those fantasies from his father in the first place. At the same time, Luke’s job is a gas station attendant, filling up other people’s vessels. So there’s an intricate set of symbols at work here.

Then again, the mention of Luke Dove being “drained” also returns us to Seth’s fantasies about vampires — particularly since he got the pulp story that inspired those fantasies from his father in the first place. At the same time, Luke’s job is a gas station attendant, filling up other people’s vessels. So there’s an intricate set of symbols at work here.

Consider: the movie’s title comes from a recollection of Cam’s, recalling a Japanese child whose skin had been changed by a nuclear bomb so that it seemed like silver — “You could see your face in it.” Dolphin frightens Seth earlier in the film by pretending to be two hundred years old, and dwelling on the slow change of her own skin; then at the end of the movie she tells him that aging is inevitable for everyone, that “your beautiful skin will wrinkle and shrivel up.” Meanwhile, reflections are visible in other skins: the skin of the black Studebaker driven by the mysterious youths from out of town, the skin of the water filling the barrel where the body of one of Seth’s friends is found. Which water in turn calls to mind a punishment Seth’s mother inflicts on him for the joke with the frog, forcing water down his throat until he pisses himself — and then speaking of water, what about Dolphin Blue’s name, and her husband who was a navy man, and the house full of nautical artifacts he’s left her?

It’s all dizzying, a web of connections that moves you from idea to idea and theme to theme. The only problem is that sometimes the characters coime to feel like abstractions, moved around for the sake of making meaningful statements. It’s understandable why the local sheriff lands on his first suspect for the killings. It’s more difficult to understand why he doesn’t take action when that first guess is proven to be wrong, especially given there are some frankly suspicious characters around who you’d expect he’d be monitoring.

It’s all dizzying, a web of connections that moves you from idea to idea and theme to theme. The only problem is that sometimes the characters coime to feel like abstractions, moved around for the sake of making meaningful statements. It’s understandable why the local sheriff lands on his first suspect for the killings. It’s more difficult to understand why he doesn’t take action when that first guess is proven to be wrong, especially given there are some frankly suspicious characters around who you’d expect he’d be monitoring.

Generally there’s a slackness of plot. There’s a kind of tragic movement in the film, as we sense characters approaching some devastating end — but there’s no real sense of tragic inevitability. Things work out badly just because that’s the way things go. The last shot, as Seth reacts to the end of his childhood, seems like a rare lapse of judgement; it’s unintentionally bathetic. You could say that the child actors aren’t particularly outstanding, but then everyone in the movie has a highly stylised delivery. I think it’s simpler to say that the conclusion to the movie’s lacking. The smoke and mirrors make for an elegant game, but at the end there’s a sudden sense of weightlessness to the story.

This is too bad, as the movie does so much right. As noted, the cinematography (by Dick Pope) and soundtrack (by Nick Bicât) are outstanding. So too is the set design; the movie captures the thingness of the early 1950s, the heaviness of rusting machines and wooden houses. And the sense of horror is excellently subtle, building up through small incidents. But again here the contrast with Lynch is notable; whether Lynch uses the supernatural or not, the building sense of dread in his films leads you somewhere. Ridley’s vision not only doesn’t allow for escape, it doesn’t allow (at least in this case) for understanding or lasting joy. There’s only an ongoing draining. “If you’re loved you’ll still be young,” says Dolphin at one point, and “innocence can be hell” — but also “sometimes terrible things happen quite naturally.” Which last seems to sum up the story of the movie.

With The Reflecting Skin over, I decided Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory still felt like a better bet than Nowhere Girl. So I crossed the street to the De Sève Theatre and tried to switch mental gears yet again, to cope with a surreal Japanese comedy about a woman’s relationship with her TV.

With The Reflecting Skin over, I decided Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory still felt like a better bet than Nowhere Girl. So I crossed the street to the De Sève Theatre and tried to switch mental gears yet again, to cope with a surreal Japanese comedy about a woman’s relationship with her TV.

Written and directed by Lisa Takeba, Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory (originally Haruko chojo gensho kenkyujo) opens with the title character telling us “This is a love story about me and my TV” before giving a quick autobiographical account of how as a child she dreamed of going away on a UFO and how she was unintentionally embarrassed by her teacher father (Fumiyo Kohinata). In the present, she’s watching a black-and-white TV (with the brand name “videodrome”) and cursing the shows she watches until the curses tick past a magic number and the television set comes to life. The TV, now calling itself — himself — ‘Terebi,’ has a male human body (Aoi Nakamura) and a face sticking through the screen. Haruko does what perhaps any of us would do: Googles “talking television.” All this before the opening credits.

The film moves along quickly, as Haruko and Terebi start a relationship, and Terebi tries to find out about his origins, and tries to find a place for a talking TV in this mixed-up crazy world of ours. Meanwhile in America other appliances start to come to life. And there are masked robbers, and a Jason Voorhees cosplayer, and pop idols dressed as the Ku Klux Klan, and, and, and …

And it somehow all works. You almost lose track of the basic girl-meets-TV, girl-loses-TV, girl-gets-TV-again plot underneath the weirdness, particularly when a last plot twist changes the conclusion like a channel unexpectedly switched. But it never quite loses coherence. There’s an emotional continuity that anchors it, however surreal it gets.

Thematically, the movie’s interested in how people get treated as objects and objects sometimes treated as people. Why does Terebi come to life? Because Haruko keeps talking to it. “I am not your escape from reality!” he shouts; meanwhile Haruko, who works at a laundromat, has a coworker (Sayaka Aoki) who gets plastic surgery to try to get her husband to pay attention to her: “Women are like home appliances,” she says, “the older they get the less attention they get.”

Thematically, the movie’s interested in how people get treated as objects and objects sometimes treated as people. Why does Terebi come to life? Because Haruko keeps talking to it. “I am not your escape from reality!” he shouts; meanwhile Haruko, who works at a laundromat, has a coworker (Sayaka Aoki) who gets plastic surgery to try to get her husband to pay attention to her: “Women are like home appliances,” she says, “the older they get the less attention they get.”

There’s some media criticism as well, of course. What is real and what isn’t become blurred. What’s a real memory and what’s a TV show? What’s pretend and what isn’t? Are costumes and fantasies an important part of life, or a way of cutting off connections to others?

The movie itself makes no nod to realism at all. It’s highly stylised, with colourful mod-influenced imagery. Terebi’s head isn’t even slightly like a real TV; it’s a cartoon of a CRT set. CGI at the end is similarly cartoony. The paranormal laboratory Haruko builds just before the movie’s climax is cardboard. Yet if it’s all done on a budget, it still builds a coherent world. And for all the unpredictability and surreality, it’s a recognisable world as well.

My only problem with the film is a feeling that the conclusion betrays the movie’s premise. Haruko makes a choice that’s more-or-less traditional in these types of fantasy-versus-reality movies. But you don’t see why she makes the choice. Or why it would possibly be a good idea. You can see that when her coworker makes a similar choice, it’s a disaster. The only thing left is to hope that the final shots are implying that the story’s not yet done.

My only problem with the film is a feeling that the conclusion betrays the movie’s premise. Haruko makes a choice that’s more-or-less traditional in these types of fantasy-versus-reality movies. But you don’t see why she makes the choice. Or why it would possibly be a good idea. You can see that when her coworker makes a similar choice, it’s a disaster. The only thing left is to hope that the final shots are implying that the story’s not yet done.

Overall, though, Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory is a happy, occasionally sexy, and generally very funny movie. It’s unpredictable, and if it’s occasionally a bit flat, it keeps moving forward. I can’t say it builds coherent characters, because that’s not what it’s trying to do; it builds stylised characters, and makes a good argument that they’re much more interesting, at least in small doses. That’s enough to call it a success.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.