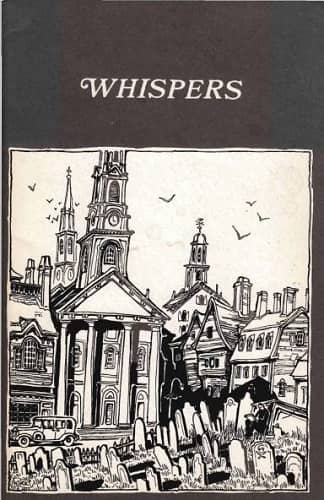

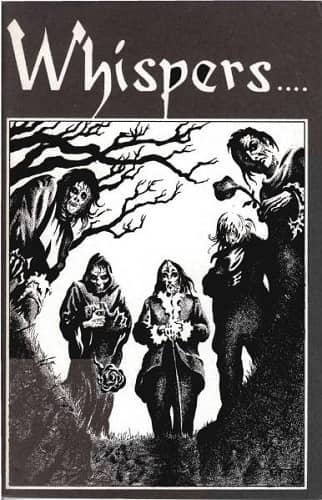

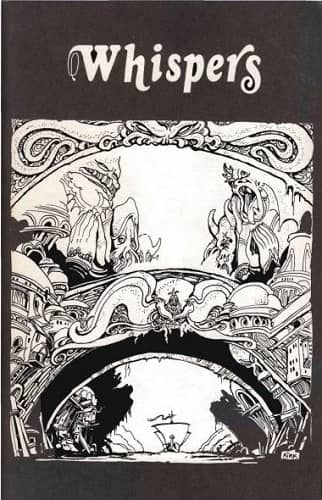

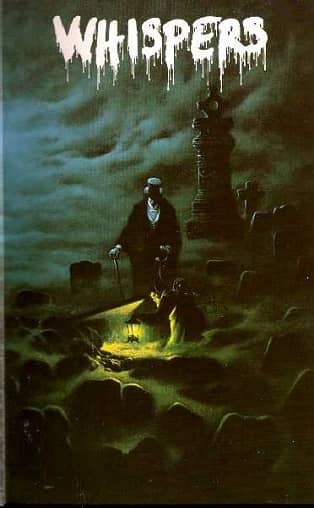

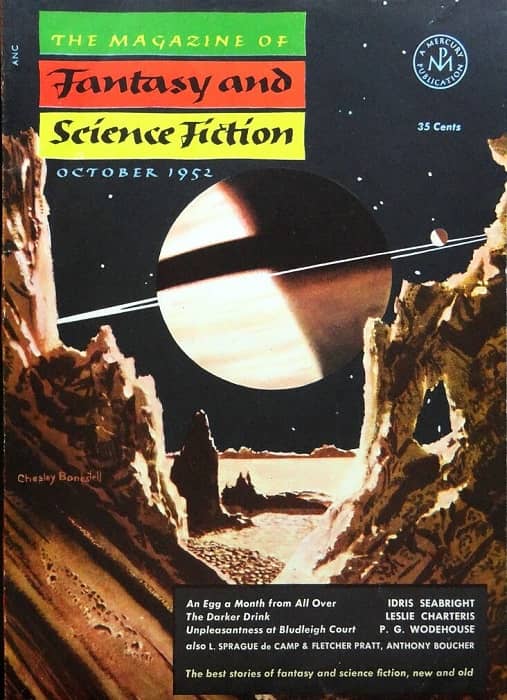

Assorted issues of Whispers, 1973-87. Issues #1, 2, 4, 9, 13-14, 15-17, 17-18, 19-20, and the final issue, 23-24.

Covers by Tim Kirk (1,3), Stephen Fabian (2,9,13-24,23-24), John Stewart (13-15,16-17), and Kevin Eugene Johnson (19-20)

When I started Black Gate magazine, I drew inspiration from small press magazines of the 70s, 80s and 90s that I deeply admired. It was a a fairly short list, but it included W. Paul Ganley’s Weirdbook, the Terminus Weird Tales edited by George H. Scithers, John Gregory Betancourt and Darrell Schweitzer, and Stuart David Schiff’s Whispers.

Whispers was near-legendary by the late 90s, when I was getting serious about starting my own magazine. The last issue had been published in 1987, but in its 15-year run it published original fiction and poems by Stephen King, Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Robert Bloch, Karl Edward Wagner, Roger Zelazny, Michael Shea, Manly Wade Wellman, Ramsey Campbell, William F. Nolan, David Drake, Ellen Kushner, Steve Rasnic Tem, Carl Jacobi, Hugh B. Cave, Phyllis Eisenstein, Joseph Payne Brennan, Dennis Etchison, Robert Aickman, Glen Cook, Charles L. Grant, Gerald W. Page, Lisa Tuttle, Richard A. Lupoff, Janet Morris, and many, many others.

It also published original artwork by many of the greatest horror and fantasy artists of the 20th Century, including Michael Whelan, Stephen Fabian, Lee Brown Coye, Allen Koszowski, Vincent Di Fate, Charles Vess, Hannes Bok, and numerous others.

One of the many inspirational things about Whispers — apart from its phenomenal success — was that it was virtually a one-man operation. Stuart Schiff grew his tiny magazine from humble beginnings as essentially a slender black-and-white fanzine in 1973 into one of the most influential horror mags of the century, with a spinoff line of paperback anthologies, limited edition hardcovers, magazines supplements, and of course a Best of collection.

…

Read More Read More