When Worse Comes to Worst: The Black Hole and Saturn 3

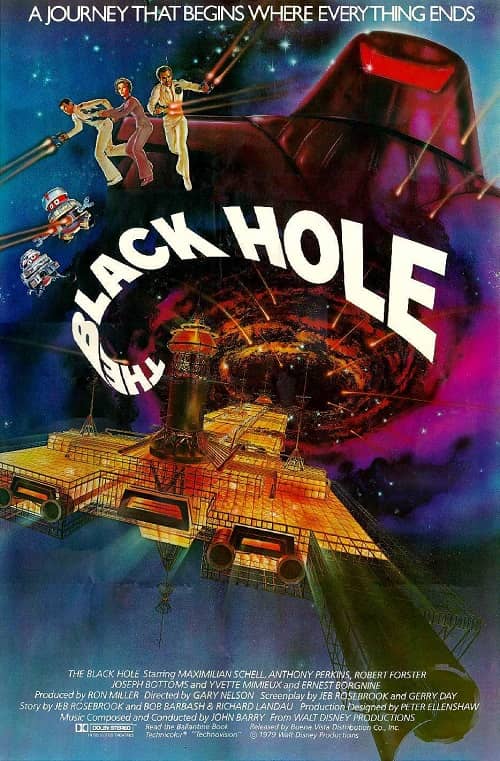

The Black Hole (Disney, 1979)

Stephen Spielberg may have said that “the arc of the cinematic universe is long, but it bends towards quality,” but that’s a crock. (Actually, he didn’t say that. No one did. But I need to establish something here, so cut me some slack, will you?) Much as we may wish otherwise, cinema history, like the other, capital H kind, isn’t linear or progressive – it’s cyclical. This means that there will be times when things are trending up and times when they’re heading down, periods of boom and periods of bust, seasons when excellence commands the stage and epochs when utter crap towers so high over everything that it blots out the sun. Perhaps no film genre demonstrates this inevitable ebb and flow better than science fiction.

Never was this more evident than during the late 70’s and early 80’s, a low end of the bell curve era if there ever was one. For every Star Wars or Alien, there was a Metalstorm or a Spacehunter. Actually, given the iron logic of Sturgeon’s Law (“Ninety percent of everything is crap”), for every Empire Strikes Back there were nine (!) Laserblasts. In fact, you could argue that this arid stretch invalidates the law altogether – by proving Sturgeon wildly optimistic. Ninety percent? Anyone who spent time in the mall multiplexes during those years could be excused for thinking that the offal percentage was closer to ninety-nine than ninety.

(By the way, if you think I’m being unduly hard on these films, we can easily talk about some of the era’s other cultural products. How about music? Where shall we start – Martha Davis and the Motels? A Flock of Seagulls? Loverboy? Yeah… that’s what I thought. Back to crappy sci-fi movies it is.)