Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Arthur and Out

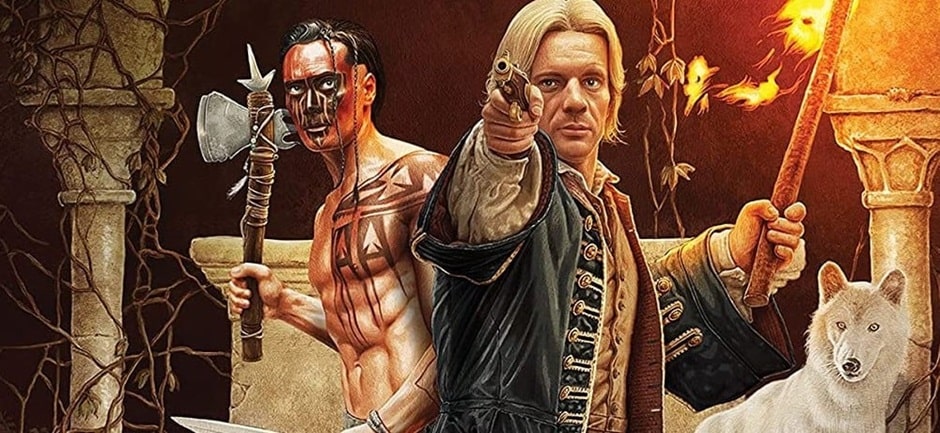

Tristan & Isolde (20th Century Fox, 2006)

Greetings, friends, and welcome to the last Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords article, at least for a while.

I’ve enjoyed hanging out with you here on the regular, but circumstances have changed for Your Cheerful Editor, and my writing output must adapt to accommodate them. For a good while, I had reached an equilibrium in my writing, balanced between work for the day-job at Larian Studios, making progress on my nine-volume Musketeers Cycle of Alexandre Dumas translations, and churning into the 21st century for the Cinema of Swords review series.

But life is change: I’ve finished the Dumas translations, we’ve gone into pre-production on Larian’s next game, and perhaps most significantly, my health is not what it was, as over the last year, in addition to the other indignities of late middle age, I’ve developed late-onset asthma. And it’s hit pretty hard, diminishing my energy and forcing a decline in productivity in my side projects.

In addition to these articles for Black Gate, for a year or three I’ve been making two weekly postings over on the Substack platform, one for the Musketeers and one for Swords. I’ve had to face the fact that it isn’t sustainable and I need to get off that treadmill. So, both Substack series have been suspended, and likewise this is my last regular article for Black Gate.