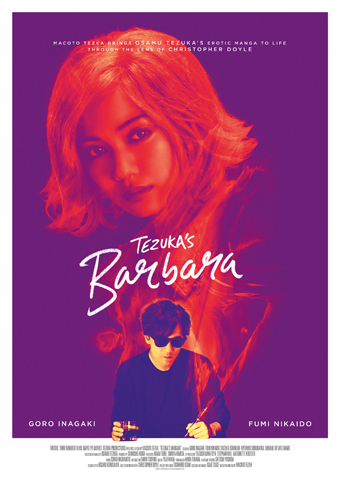

Fantasia 2020, Part XII: Tezuka’s Barbara

The chain of inspiration behind a work of art can be stunning to behold. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffman was a musician, critic, and fiction writer in the early nineteenth century whose surreal and gemlike short stories are wonders of early fantasy. Some of those stories were worked into the libretto of Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les contes d’Hoffmann. Adapted to films at least three times, most notably by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951, Offenbach’s work would inspire the great manga creator Osamu Tezuka in 1973. A sexually-charged tale with elements of the occult, Tezuka’s Barbara was an erotic story about a frustrated manga creator who met a woman who might be a literal muse. Now Tezuka’s Barbara is a film directed by Macoto Tezuka, Osamu’s son, with a script from HIsako Kurasawa; and it played at the Fantasia Festival on August 25.

The chain of inspiration behind a work of art can be stunning to behold. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffman was a musician, critic, and fiction writer in the early nineteenth century whose surreal and gemlike short stories are wonders of early fantasy. Some of those stories were worked into the libretto of Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les contes d’Hoffmann. Adapted to films at least three times, most notably by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951, Offenbach’s work would inspire the great manga creator Osamu Tezuka in 1973. A sexually-charged tale with elements of the occult, Tezuka’s Barbara was an erotic story about a frustrated manga creator who met a woman who might be a literal muse. Now Tezuka’s Barbara is a film directed by Macoto Tezuka, Osamu’s son, with a script from HIsako Kurasawa; and it played at the Fantasia Festival on August 25.

The movie begins with bestselling writer Yosuke Mikura (Gorô Inagaki) meeting an apparently homeless young woman in a subway tunnel, and taking her home with him. This is Barbara (Fumi Nikaido, Fly Me to the Saitama and Inuyashiki). She critiques his writing, accusing him of being too safe and commercial, but soon she’s saving him from voracious women who turn out to be mannequins or dogs. Mikura pursues Barbara, but to win her he must convince her mother, an antique-store owner named Mnemosyne (Eri Watanabe) — but she has strange connections, and tragedy lurks in the wings.

Reality and dreams blur over the course of the film, and I’m not convinced the movie does a good job setting up either a coherent reality or an effective oneiric sense. In part as a result, I also did not feel the movie gained anything in its mix of real and dream. The conclusion in particular moves past tragedy to almost insist it’s a hallucination, but where that hallucination started is less clear. It’s possible, maybe even intended, to read the whole movie as a reverie in the head of Mikura. But I find no particular thematic weight in that approach. Whether viewed entirely or partially as a dream, Tezuka’s Barbara resists cohering into a meaningful story.

Which again might be the point. The movie does strain mightily after a sense of strangeness. I would say it largely fails to reach any consistent surreal atmosphere. There is a lot of sex, but a countervailing coldness leaves these scenes clinical and not passionate; as an asexual I can’t claim to be very perceptive when it comes to sex scenes, at this point in my life I can usually at least see what a film’s trying to do. In this case I think it’s trying to create a feverish sense, trying to speak about a fusion of sex and art. Certainly it investigates the idea of the muse from a number of angles. But nothing comes out of it. It never really takes flight.

One of the cinematographers is Christopher Doyle (Hero, In the Mood for Love), so the movie looks fine, but it also feels glossy in a way that works against the attempt at going beyond the real. It might be said to capture something of the sheen of 9 1/2 Weeks, I suppose, and there are enough non-narrative montages of Barbara doing nothing in particular that it structurally insists on Mikura’s fascination with her overriding his sense of linear time. To the extent that the montages can be said to have any narrative function at all.

One of the cinematographers is Christopher Doyle (Hero, In the Mood for Love), so the movie looks fine, but it also feels glossy in a way that works against the attempt at going beyond the real. It might be said to capture something of the sheen of 9 1/2 Weeks, I suppose, and there are enough non-narrative montages of Barbara doing nothing in particular that it structurally insists on Mikura’s fascination with her overriding his sense of linear time. To the extent that the montages can be said to have any narrative function at all.

Tezuka’s Barbara does try to tell a story about muses, then, and their importance for artists. Of course Barbara’s mother has the name of the mother of muses; of course the embodiment of memory runs an antique store. But what is the point? Offenbach’s opera was clear enough, a story about an artist abjuring earthly love to dwell with his muse and produce art. Here Mikura’s involved with the daughter of a politician, so nominally the contrast of sacred art and earthly affairs becomes more pointed — but you never get the sense that Barbara’s rival ever really held much of an appeal for Mikura. And it’s hard to get a sense of Mikura as an artist. We don’t get a reading of his work, don’t understand whether his fears of being overly populist are valid or not.

Barbara, meanwhile, is in dire danger of being a manic pixie dream muse. If so, there’s some justification if she is in fact literally a dream, literally a fantasy of a straight male artist with a tendency to weaken his work by repeating pop tropes. That doesn’t necessarily make the movie interesting to watch, though. If Barbara’s crueller than the usual MPD girl, she also comes to a crueller fate. It’s an odd take on a union of artist and muse, and I found it unconvincing.

The very final moments of the movie can be read in a number of ways, none of them entirely satisfying. Has Mikura escaped a case of writer’s block? Or is he obsessively returning to a fantasy? Has he improved as an artist? Was he ever worth the attention of a muse? Even if so, has anything been resolved? Or is resolution impossible? The movie’s attempt at blurring reality makes the conclusion opaque. There’s just enough in this movie to make it worth discussing in thematic terms, even if the plot’s incoherent, but not I think enough to provide a satisfying experience purely on that symbolic level.

The very final moments of the movie can be read in a number of ways, none of them entirely satisfying. Has Mikura escaped a case of writer’s block? Or is he obsessively returning to a fantasy? Has he improved as an artist? Was he ever worth the attention of a muse? Even if so, has anything been resolved? Or is resolution impossible? The movie’s attempt at blurring reality makes the conclusion opaque. There’s just enough in this movie to make it worth discussing in thematic terms, even if the plot’s incoherent, but not I think enough to provide a satisfying experience purely on that symbolic level.

The acting’s solid, the look of the film is fine, individual incidents are watchable. But some of those incidents don’t develop or pay off in any kind of satisfying way, in terms of either plot or theme; in particular a sub-plot about voodoo dolls doesn’t seem to have an obvious conclusion or indeed reason to exist. Perhaps the ultimate failure of the film is its failure to build an atmosphere. A visit to a fetish bar feels as though it’s trying too hard, and overall the movie’s too literal for a dream-world and too lacking in texture for reality. It’s implausible without being surreal, even though it’s admittedly unpredictable. But for all its weirdness and explicit sex, it feels commercial, safe, in the way Barbara-the-character criticised Mikura’s work. Art imitates itself.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.