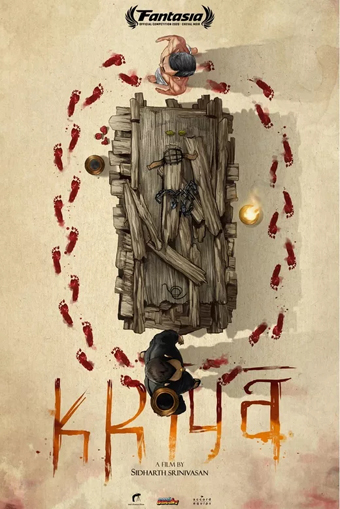

Fantasia 2020, Part XXVII: Kriya

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.

Religion’s a recurring subject for horror, and for a lot of reasons; there’s a lot in there to be scared about. More, from at least the 18th century onward writers have followed Edmund Burke and Ann Radcliffe in linking horror with the sublime. When horror fiction in the West has grappled with religion, naturally enough it’s tended to use Christian symbols, ideas, and sometimes even theology — whether in something as simple as the crucifix turning away a vampire, or in something more central to the story, as showing the birth of Satan’s child in The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby.

Of course, horror from other traditions may use religions closer to hand. Thus Kriya, an Indian film written and directed by Sidharth Srinivasan. A little like 2015’s Ludo it uses horror movie ideas and images in an Indian context, in this case placing black-magic versions of Hindu rites at its core. It’s Srinavasan’s third theatrical feature, but his first horror film. For me, as an outsider to the tradition he’s examining, it worked quite well.

It opens in a nightclub, where a mysterious, beautiful woman named Sitara (Navjot Randhawa) invites the DJ, Neel (Noble Luke), to take her home. Neel finds her home is a palatial estate, where Sitara’s dying father (M.D. Asif) is lying gagged and bound. With him are Sitara’s mother Tara Devi (Avantika Akerkar) and younger sister Sara (Kanak Bhardwaj), as well as the family servant Magdali (Anuradha Majumder) and an older priest, or pandit (Sudhanva Deshpande). Sitara wants Neel to take part in the funeral — certain rites can be performed only by the son of the family, and as there’s no son, she hopes Neel will fill in. But there’s something deeply strange and sinister in the old house and the weird family. As the night goes on the wrongness of the place becomes clearer, and Neel senses the wrongness even as he’s pulled deeper into it.

This is not exactly a haunted house story, but is certainly a story about a house-bound horror. As such the sense of place and the physical state of the location is important, and Kriya does not disappoint here. The sprawling mansion exudes a palpable sense of decay, the skin-crawling feel of a thing slowly dying, a shell that cannot be lit by the few small lives within it. The story mostly takes place over the course of a single night, and that night is thick and dark, manifesting in deep shadows everywhere inside. According to Srinavasan, in a fascinating extended question-and-answer panel alongside some of the cast, the building’s a 150-year-old building from the time of the Raj; I didn’t notice any overt thematic overtones to colonialism in the narrative, but I suspect there’s an implication there about Sitara’s family, their aristocratic aspect, and their relationship to power.

But if there’s a Western architectural vocabulary underlying the house, the sense of an Indian setting is nevertheless deep, and central to the film. The plot is fundamentally an interrogation of Hindu practice, and religious practice in general. And the horror of the film, not just the supernatural aspect but the motive for the inhuman things done to human beings, has to do with belief and ritual. Again, from the Q&A, Srinavasan observed that “Kriya, loosely, relates to last rites or rituals.” Part of the theme of the movie is to do with what happens when precepts are followed without being understood. (Also in the Q&A, the cast spoke about the Hindi dialogue as being especially elaborate, often quotations from religious texts.)

There’s also an examination of gender roles. The rituals around which the film revolves are extremely gendered, and much of what happens in the film is a function of what happens when ritual requirements meet reality — in this case, the reality of a family without a son to play the needed male part in a rite. On the other hand, the movie does not lack for empowered women. Still, it can be read as a story about the monstrous choices women must make within a patriarchal belief system; about what patriarchal customs do to women, and what in those circumstances their limits must be.

There’s also an examination of gender roles. The rituals around which the film revolves are extremely gendered, and much of what happens in the film is a function of what happens when ritual requirements meet reality — in this case, the reality of a family without a son to play the needed male part in a rite. On the other hand, the movie does not lack for empowered women. Still, it can be read as a story about the monstrous choices women must make within a patriarchal belief system; about what patriarchal customs do to women, and what in those circumstances their limits must be.

If the themes are weighty, the story’s well-handled. Much of it’s about Neel working out what’s going on in the house, and the nature of the family and their priest. You want him to leave, though you understand why he stays. There is a point toward the end where he consciously turns down escape, and you see the road not taken. And it’s a choice that makes emotional sense, given everything that’s happened to that point. Much of what happens in the old house is character-based drama, and it is Neel’s character that determines his fate. There aren’t ghosts rattling chains, though there’s enough of the supernatural to build a clear atmosphere.

And there is a sense of the sublime, in the historicity of the place and the overwhelming air of ritual. There’s no doubt that this is a horror film, and in a very real sense it’s a traditional gothic with the genders flipped: instead of a woman marrying a sinister male figure tied to a decaying house, it’s a man brought into a woman’s family home. What keeps him there is a complex combination of emotions for the woman and sense of religious duty, which at least echoes some early gothics. The 18th-century English gothic novels were often set abroad in Catholic countries, consciously or unconsciously speaking to fears about excessive religiosity. There’s maybe a bit of that here.

And there is a sense of the sublime, in the historicity of the place and the overwhelming air of ritual. There’s no doubt that this is a horror film, and in a very real sense it’s a traditional gothic with the genders flipped: instead of a woman marrying a sinister male figure tied to a decaying house, it’s a man brought into a woman’s family home. What keeps him there is a complex combination of emotions for the woman and sense of religious duty, which at least echoes some early gothics. The 18th-century English gothic novels were often set abroad in Catholic countries, consciously or unconsciously speaking to fears about excessive religiosity. There’s maybe a bit of that here.

That literary theme hasn’t often made to the movies, so far as I can see. Relatively few Western horror films are critical of Christianity; I think mainly of Larry Cohen’s God Told Me To, which is really something quite different. But Kriya’s prepared to examine Hinduism with a literally critical lens — not necessarily wholly negative, but taking seriously the requirements and beliefs of the faith. I do not know what somebody raised with that tradition would think of the film. But for me it works admirably as a distinctive and effective story.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.