Carl Burgos and Air-Sub “DX”

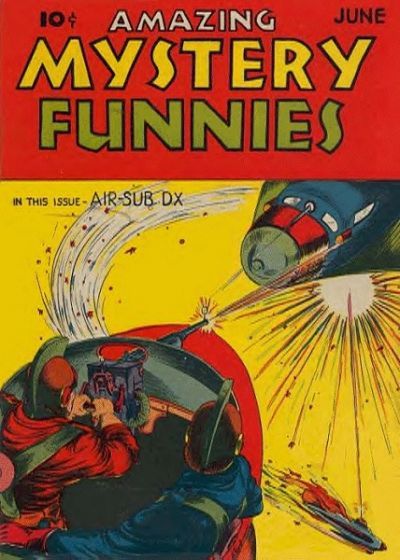

Amazing Mystery Funnies #10, June 1939, cover art by Bill Everett

Twenty-two-year-old artist Carl Burgos entered comics in 1938. He almost immediately started creating his own features as artist/writer, achieving immortality in the field when an android bizarrely named the Human Torch burst into flames in the legendary Marvel Comics #1 (October 1939), the same issue that introduced Bill Everett’s Sub-Mariner. The Torch’s name got passed on to Johnny Storm when The Fantastic Four debuted and the original received one of the weirdest revivals in comics’ history as the Vision in Avengers #57 (October 1968). (No relation to a 1940s character called the Vision.) The Avengers’ brainier members quickly traced his heritage to that android created by scientist Phineas Horton in 1939, conveniently forgetting that Burgos himself stopped calling him an android after about three issues. For the next decade, the Human Torch seemed to be a regular human whose body was fire, or could be set on fire, or contained fire, or something else equally unclear. The Golden Age lacked continuity police.

Probably only a few comics historians understand how obsessed Burgos was with artificial people. Just before the Human Torch he created a cyborg or robot named Iron Skull whose origin story changed every couple of issues and a few months later he produced an unquestioned android, Manowar the White Streak. Despite the name, Manowar was a utopian who fought evil in the cause of peace. (And wasn’t white. And not the same as Paul Gustavson’s contemporary Man of War for the same company. Writing comics history is footnotes all the way down.)

Comic books were so new in 1939 that, like Leacock’s Lord Ronald, they rode madly off in all directions. Superman, the the sensation of 1938, spawned more of what we now call superheroes but they didn’t dominate. The 64-page comic books had already made a swift transition from reprinting newspaper comic strips, with 30 or more titles inside a single book, to all-new titles containing eight stories (seven pages each to account for ads and filler material) and eight different heroes. How they decided which contributed to sales is anyone’s guess, although letters from kids surely guided them, but tables of contents changed virtually every issue.