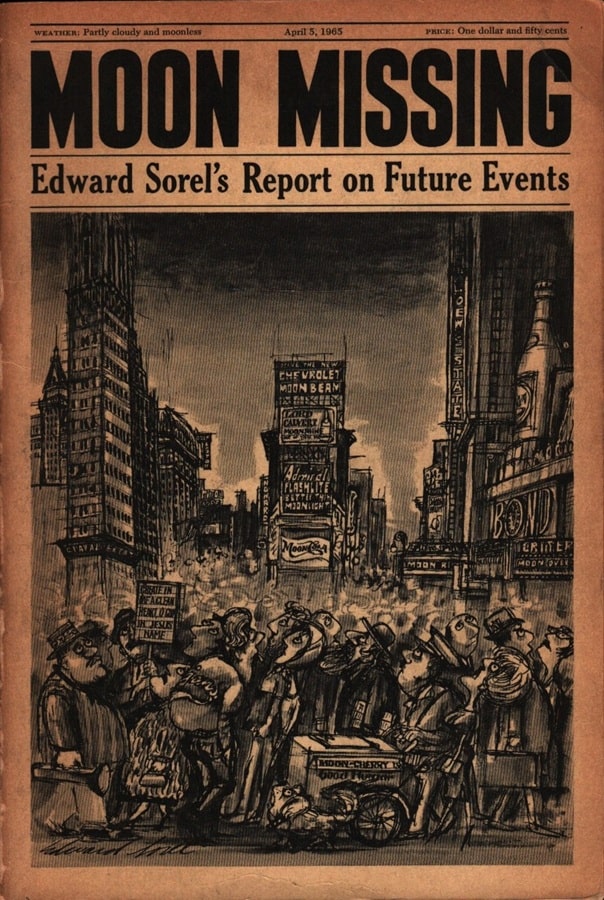

When Satire is Overwhelmed by Reality: Moon Missing: Edward Sorel’s Report on Future Events

At about 1:46 am EST in the middle of the American night of April 4, 1965 the Moon disappeared. The American people were informed the next day at a Presidential news conference. President Kennedy was in no way responsible, said Allen Dulles, disgraced former CIA director but now Secretary of the Exterior, tapped to safeguard American interests in outer space.

Cartoonist, caricaturist, satirist Edward Sorel published Moon Missing in 1962. He had no need to prognosticate the future; the world around him gave him all the ammunition his ink Speedball B6 required.

So insistent are we today that the early Sixties were a more innocent time that the reality of the fear, paranoia, tension, and general unhappiness of the era can only be exhumed from period pieces. Sorel’s vision of the craziness ready to be let loose by a global event relied heavily on contemporary names in the news, but to find frighteningly many parallels in today’s world the names need only to be changed to modern equivalents.