The history of comic strips sometimes seems like a roll call of male names. The Katzenjammer Kids, Little Nemo, Tarzan, Moon Mullins, Li’l Abner, Barnaby, Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, Joe Palooka, Barney Google, Mutt and Jeff, Dick Tracy, Harold Teen, and the name of names, Rube Goldberg’s Boob McNutt. Even Blondie heads a strip that’s 99.9% about Dagwood.

Probably the most famous female comic strip heroine is Little Orphan Annie. Digging into archives brings up a roster of mostly forgotten others: Ella Cinders, Etta Kett, Winnie Winkler, Invisible Scarlet O’Neil, Little Annie Rooney, Dixie Dugan, Betty, Nancy, and Dimples, a roster that will bring few images to mind.

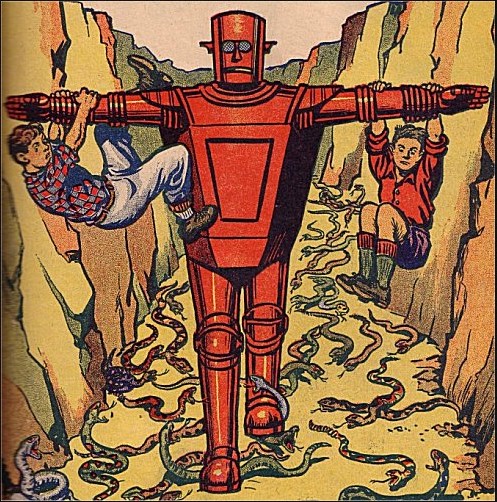

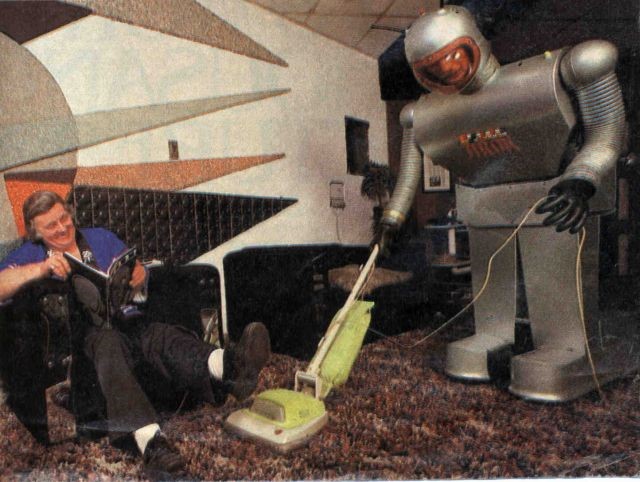

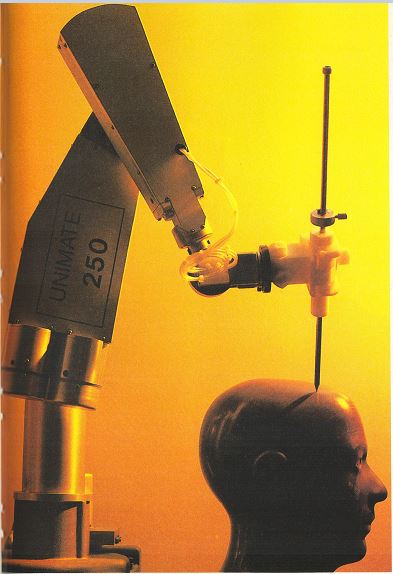

Only a handful of comic strips ever ran a major series starring robots, and those were mostly in the male-oriented science fiction strips. Two rare exceptions occurred in Invisible Scarlet O’Neil and Ella Cinders, but both robots were drawn and referred to as males. (How do you sex a robot? The top set of swimmerets on a female’s tail are soft, translucent, and crossed at the tips. A male’s swimmerets are bony, opaque, and point up toward his body. Sorry. That’s how you sex a lobster. You sex robots by the length of their hair and the size of their breasts, just like humans. Check below if you don’t believe me.) Finding a strip with a female star going up against a female robot is the rarity of rarities.

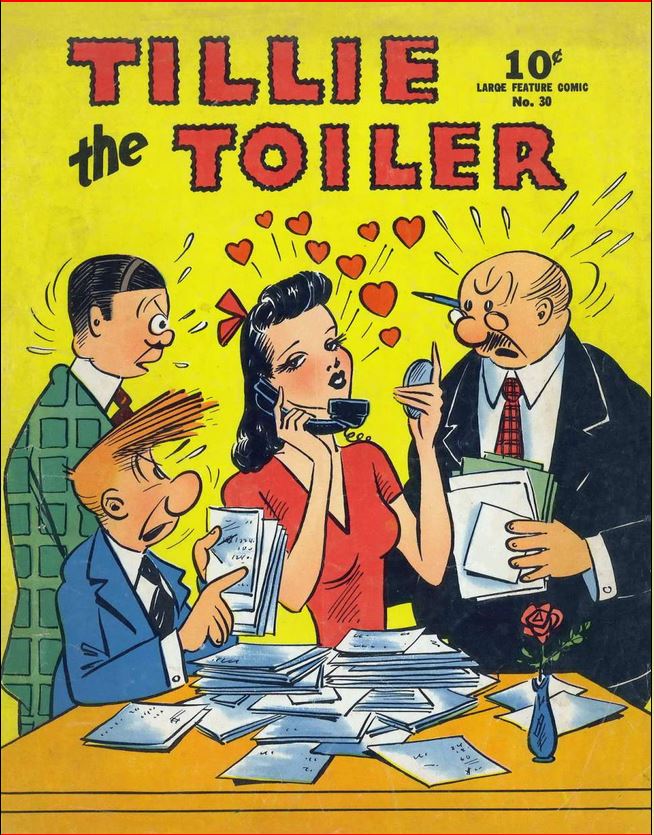

Today’s unique find is Rosie the Robot in Tillie the Toiler. (Not the far more famous Jetson’s Rosie. Rosie is to girl robots what Robbie is to boy robots: hideously overused.)

…

Read More Read More

![1937-10-17 San Francisco Examiner [American Weekly 3] A Whole World of Metal Men, The Last Robot](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/1937-10-17-San-Francisco-Examiner-American-Weekly-3-A-Whole-World-of-Metal-Men-The-Last-Robot.jpg)