Man of Steel vs. Man of Metal

Back in 1870, the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser newspaper bannered on its front page the arrival in New York of a troupe of French champion strongmen, including Monsieur D’Atelie: the “Man of Steel.” The article described him as:

33 years of age, and rather slightly built. He has a prepossessing, benevolant expression of countenance. His specialty is lifting objects with his teeth, including a live horse by means of a band round its body. D’Atalie weighs 150 pounds.

D’Atalie is the first person I’ve found to bear the sobriquet “man of steel,” although its metaphorical uses go much farther back. He certainly wouldn’t be the last. A certain Russian communist adopted the name Stalin in 1912, which can be translated as “man of steel,” and who was fairly well known by the 1930s.

Another “man of steel” made his first appearance in 1938, on the cover of Action Comics #1. Assiduous readers of Action Comics #6, later in 1938, could have caught a newspaper headline from the Daily Star (the Daily Planet wouldn’t get mentioned until 1940) describing this mystery figure as a “man of steel”. Superman and “Man of Steel” have been inextricably interlinked for 81 years.

Writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster were science fiction fans since their early teens. They loved every wild gadget and weird landscape that the pulp magazines served up, robots unquestionably among them. Siegel wrote a robot story for his high school newspaper. One of their very first strips, “Federal Men,” which started in New Comics in 1936, featured a gigantic robot looming over the city skyscrapers, an image as iconic and as influential as Superman. The only question was how soon they would introduce a robot in a Superman strip, matching the figurative man of steel with a literal one.

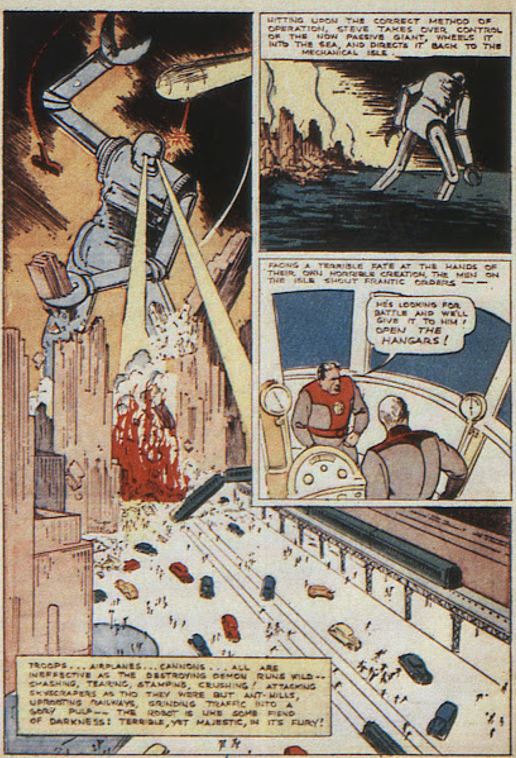

Those who had 1942 in the office pool won the pot. World’s Finest Comics #6, Summer 1942, had the Man of Steel square off against Metalo, dubbed here the “Man of Metal.” (Notice that even in 1942, Superman was suspicious enough that the police think he might be involved in the crimes actually committed by Metalo.)

|

|

Disappointingly, Metalo is just a proto-Iron Man rather than a true robot. Superman kills him with ease.

“Superman doesn’t kill!” I can hear you gasp. Oh yeah, then how do you explain these panels?

That’s clearly a roundhouse punch that’s knocking Metalo into the lava. Superman flies off assuming that “the world is rid of that terrible Metalo.” He can’t know that Metalo saved himself by grasping a protruding edge and vowing that “in our next encounter — he’ll pay for it!”

The big blue boy scout doesn’t have pockets, so it’s a good thing Metalo never shows up again in the Golden Age. They don’t even go Dutch on a check.

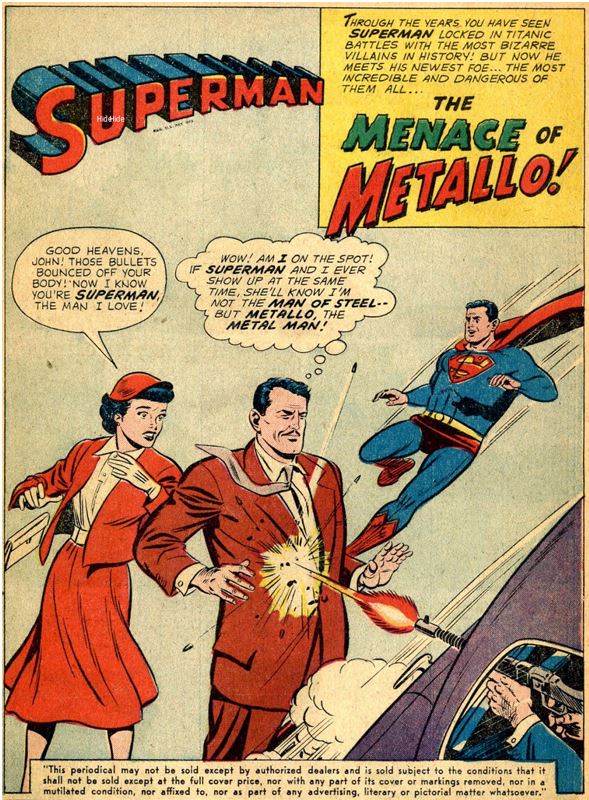

The Silver Age brought a different side of robots to a brief flicker of existence. Superheroes had taken a double blow after WWII. They fell out of favor among older readers who preferred the more adult crime and horror comics, while a flood of kiddie comics appeared to attract younger readers. DC made their remaining superheroes light and fluffy, aimed at about a ten-year-old audience, but still got tarred by the broad brush of the anti-comic forces. A Comics Code was established in 1954. Superman would no longer kill, even by accident or implication.

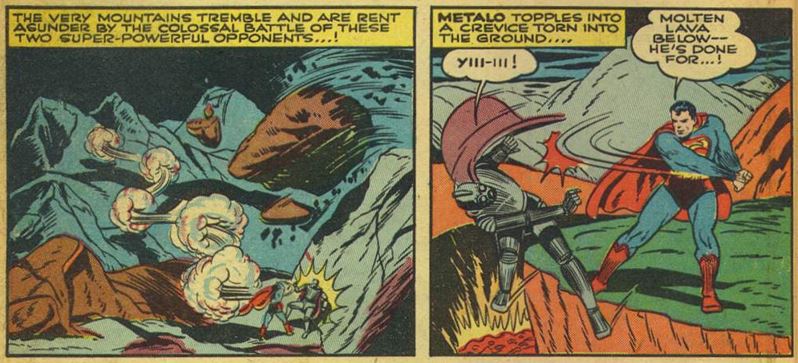

Superboy generally found adventures in the mythic small-town America of good and noble white people, little different from the protagonists in the children’s section of a library. The June 1956 issue, #49, was a touch darker, an odd anomaly.

Superboy is once again called upon to save the world, this time from a comet that, if it hit the sun, would cause huge explosions, destroying the earth. (Borrowing words from science with total disregard to their actual meaning had always been endemic in comics.) A single puff destroys the comet but Superboy encounters a cloud of kryptonite-containing cosmic dust and falls onto a convenient asteroid, a Robinson Crusoe of space, but with less hope of survival. Surrounded by kryptonite closing in on him, he will die within a week.

Having given readers the literary cue, Superboy must now discover his man Friday. Of all the asteroids in all the solar systems of the universe, this one has a robot, a Kryptonian robot yet, named Metallo with two “l”s. As a native of Krypton, Metallo is super-powered under a yellow sun and is equally vulnerable to kryptonite. (Think about this. Would a Kryptonese locomotive stop in its tracks if they were made from kryptonite?) Jumping quickly past the fact that the asteroid not only has a breathable atmosphere but contains trees with edible fruit – Superboy apparently needs to eat and drink – a miracle ending must be pulled out of a hat. Since Superboy’s name is in the title, Metallo gallantly sacrifices his life, as all good robots eventually do for the superior humans. At the last moment he seals the sleeping Superboy in a lead-lined capsule and uses his super-strength to hurl it to Earth. There’s not a dry eye in the house.

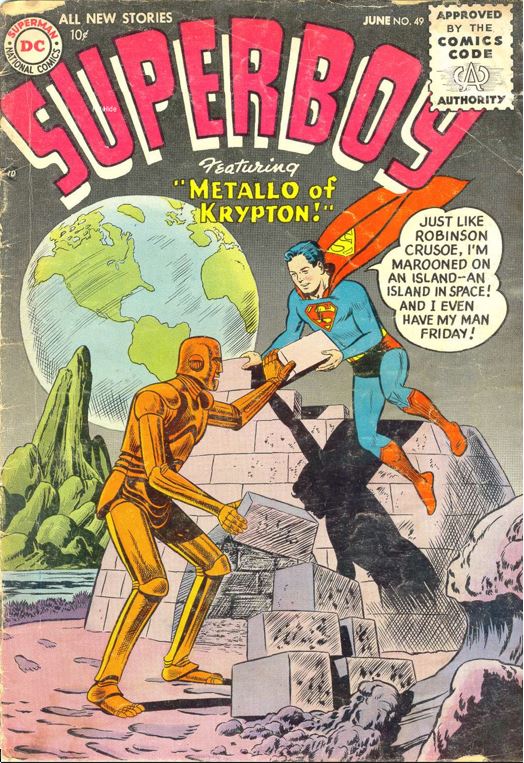

Superman was so fantastically, instantly popular that a Superman newspaper comic strip – a medium ten times more prestigious than comic books – was launched within a year of his debut. Still going in 1958, the daily strip was read by millions, far overshadowing the comic books. (A legion of superhero writers and artists worked on the strip. My best guess is that Bill Finger wrote this series over Curt Swan’s art.) A five-month daily series started in December when a car crashes in the hills outside of Metropolis. The victim, named John Corben, is near-death. No ordinary surgery can save him. He’s found by no ordinary doctor. The kindly Professor Vale puts his brain into a superstrong metallic body.

Corben, nicknamed Metallo, is a conscienceless crook; when he learns that the uranium capsule powering his mechanical heart needs constant replacement (apparently a unique isotope with a half-life of a day), he has no qualms about stealing all he requires. He even takes a science reporter job at the Daily Planet so he can legitimately scout out sources. And when his metal body blocks bullets meant for Lois Lane, the starry-eyed girl reporter immediately assumes that he is Superman and lets her long-standing love for Supe pour all over Metallo, who now can’t do wrong in her eyes.

Worse, Metallo discovers the one element that will permanently power his heart. Unless you’re a ten-year-old, you’ve already guessed that element is kryptonite. Superman is doomed, and so is Lois, who knows Corben’s secret and must die. Supe has some kryptonite in a lead safe, which Metallo steals. Don’t do it, Metallo! It’s a trick! The glowing bauble is a fake. When Metallo tries to fly off, he plunges to his death. Superman has killed again. No, seriously. Corben’s brain is still in the metallic body, remember.

Comic strips weren’t subject to the Comic Code; they were watched over by the newspaper syndicate and held to standards that required serious adventure strips to be as family-friendly as Disney. Death had to be by misadventure. No telling how this one slipped through. Perhaps everyone was blinded by the use of the word “robot.”

But not the Comic Code censors. Metallo’s story was retold in the May 1959 Action Comics, #252 by Robert Bernstein and Al Plastino. Although shortened and condensed, the comic book faithfully followed the original until the ending. Metallo takes fake kryptonite kept for a magazine photo shoot, not a trap laid out by Superman. His subsequent heart failure is therefore his own doing.

That Metallo also disappeared for many years. Perhaps his comic book appearance was merely a quicky fill-in story. Action #252 is the issue that introduced Supergirl to the DC Universe. Nothing else penetrated.

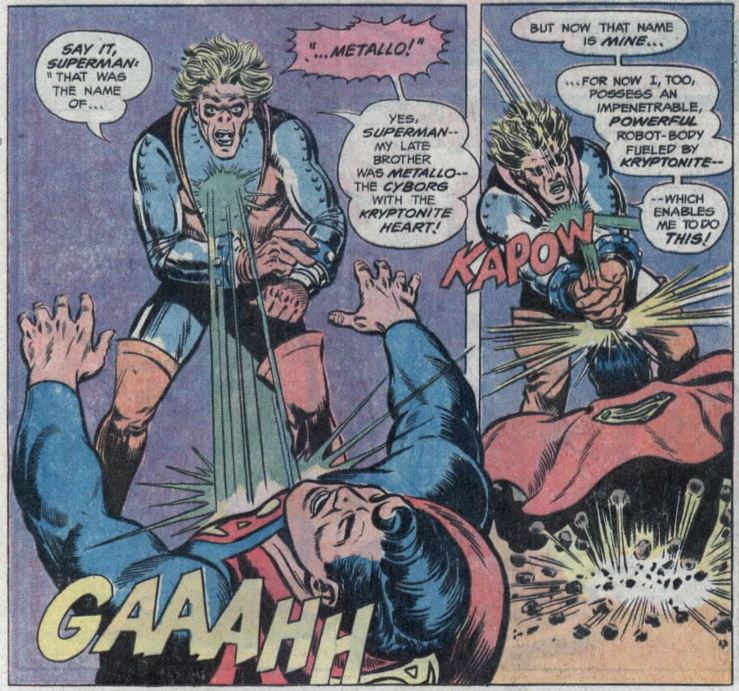

Almost two decades passed before Metallo resurfaced, or at least a Metallo did. In Superman #310, April 1977, John’s brother Roger Corben undergoes a similar operation. Not only has the art advanced, so has the science. The new Metallo is properly called a cyborg rather than a robot.

Just as in the last panel of the original Metalo story, this Metallo is also revealed not to have died after he apparently “self-destructs.” Not that it did him much good. His only other appearance came as a cameo in Superman #418, April 1986, when he is swiftly dispatched by Superman XS (an alien standing in for Supe, while he battles an enemy in another galaxy). (Databases slot this Metallo under Roger Corben, but his given name is never mentioned in the issue.)

By the 1980s, a wave of nostalgia rolled through comics, making Golden Age material that once seemed old-fashioned, poorly-drawn, and thuddingly-written dreck now glisten with a patina of age.

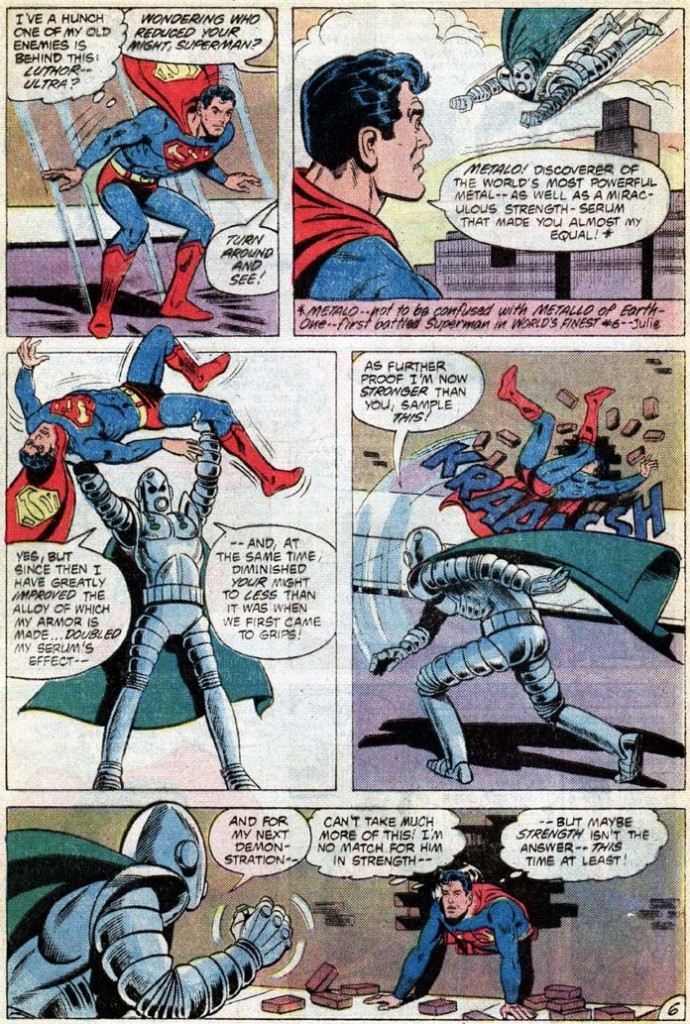

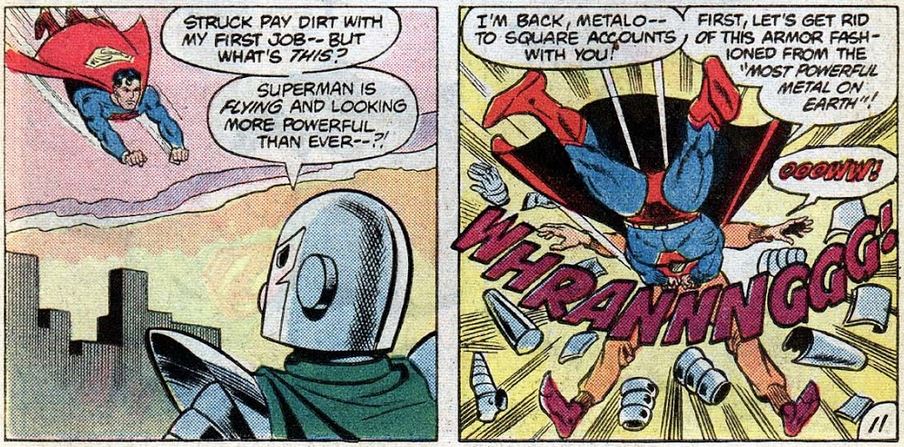

Or so I assume from The Superman Family #217, April 1982. At that time, several reboots ago, the Golden Age heroes had been explained away as living in an alternate universe, on Earth-Two. That’s how there could be two different Flashes, two different Green Lanterns, and two Supermen who seemed superficially identical but actually had crucial differences. Writer E. Nelson Bridwell pretended everyone knew the complete history of Superman in the pre-WWII era for a tale called “Back to Square One” that brought the old one “l” Metalo back for a last hurrah. Metalo zaps Supe with a power drainer, making the Man of Metal stronger than the Man of mere Steel.

With Lois’ encouragement (on Earth-Two they are married and he is the editor of the Daily Planet) he duplicates the course of muscle-building that explains away his rise from the relative shortage of superpowers he displayed in the first year of Action Comics to the unbeatable, supersonic powerhouse he became a few years later. After 48 hours of unrelenting bodybuilding, he’s more than a match for any mere strongman.

All that, and he writes his own story of victory under Lois’ name while she takes a well-deserved nap after two exhausting days of coaching.

Even in those naive 1980s, the growing multiples of alternate worlds made necessary by DC incorporating all its modern innovations along with the various comic lines they’d bought up over the years meant that keeping continuity straight was beyond any normal reader or, worse, writer. Crisis on Infinite Earths, starting in 1985, was a year-long crossover reboot that killed off hundreds of characters and brought the DC Universe down to a single continuity, from which it could re-establish the characters from scratch.

Alan Moore ended the almost five decades of Superman with the classic imaginary story “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” which ran in Superman #423 and Action Comics #583, the last issues of those ancient titles. Set in 1997, it envisioned a world without Superman after his worst enemies ganged up on him. A squadron of Roger Corben-style Metallos, everyday people converted into cyborgs, were among them.

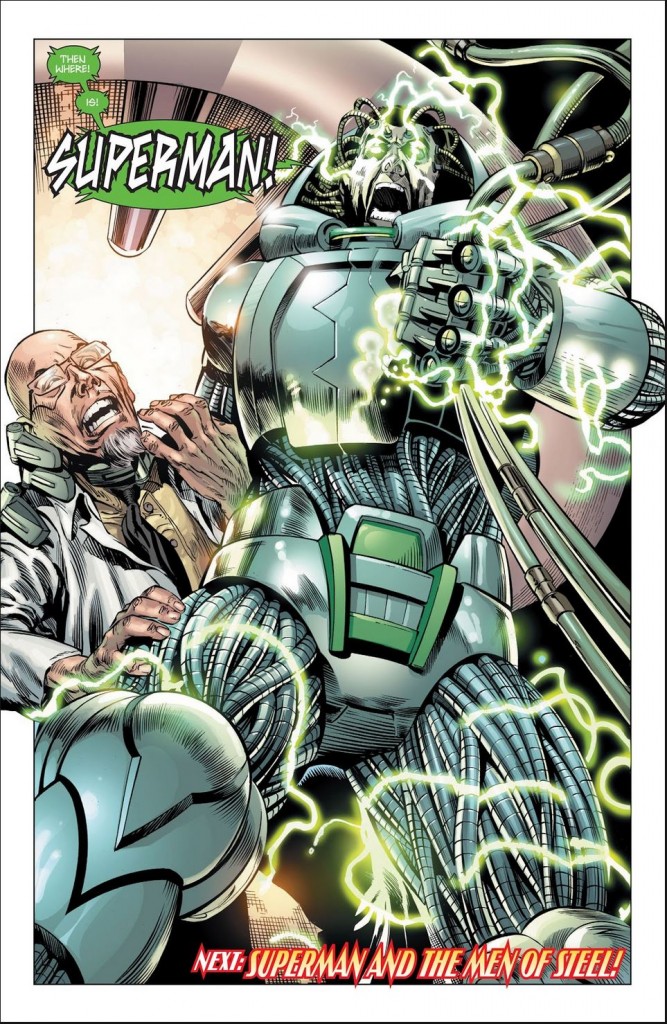

John Byrne got the plum job of re-imagining Superman, starting with a six-issue miniseries called The Man of Steel. A new title, Superman Vol. 2, #1, cover-dated January 1987, started the character in his new life. Guess who received the honor of being Superman’s first great superpowered foe? Yes, it’s the man with the kryptonite heart, the Man of Metal, the one and only John Corben, bigger, stronger, and deadlier.

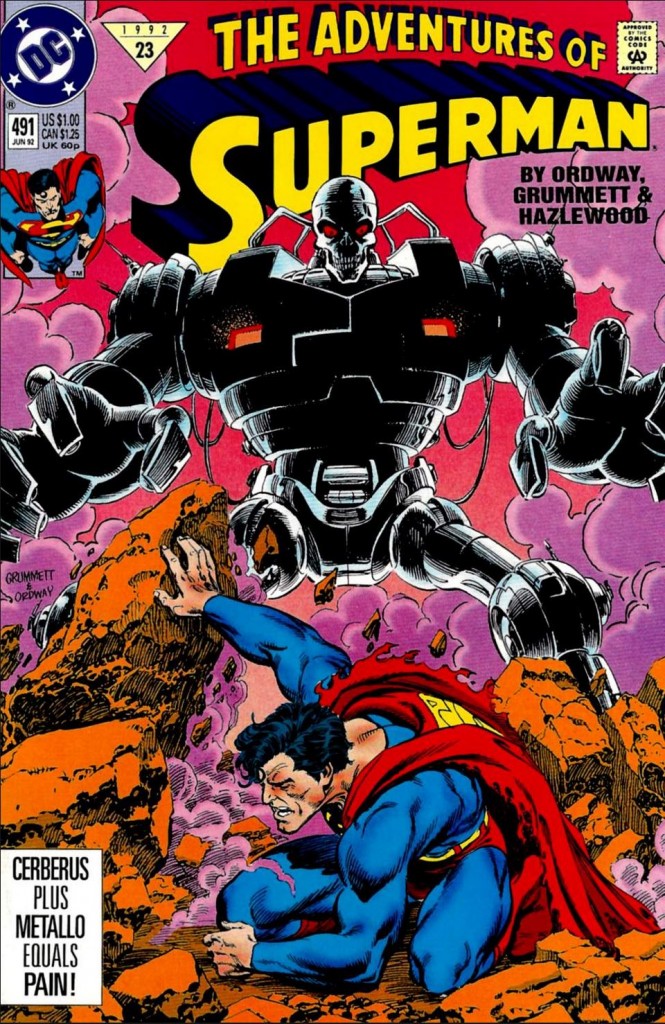

The reboot got rebooted a decade later, and again a decade after that, and maybe half a dozen times since, pureeing the classic and rethought Supermen in outlandish ways. I doubt anyone in existence, including the DC editors and historians, have managed to read every issue of every title in DC’s now near-century of history. That’s what Wikis are for, and the many databases that are devoted to DC characters remind us that Metallo, in many shapes and forms and identities, most of them called John Corben, has been resurrected in the comic books and television shows and cartoons and wherever else superheroes are sold. He even became Lois’ personal guardian recently. These two examples are from Adventures of Superman #491, June 1992 (having continued the numbering of Superman vol. 1) and Action Comics vol. 2, #3, January 2012.

|

|

As long as there’s a Superman, a Man of Steel, there will be a robot, a Man of Metal, to oppose everything he stands for. Robots, after all, cannot be killed. They will outlive us all.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Telelux and Rastus: Westinghouse’s Forgotten Robots. His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is scheduled for a Summer release.