See, this is my opinion: we all start out knowing magic. We are born with whirlwinds, forest fires, and comets inside us. We are born able to sing to birds and read the clouds and see our destiny in grains of sand. But then we get the magic educated right out of our souls. We get it churched out, spanked out, washed out, and combed out.

And so begins the best piece of writing I’ve come across.

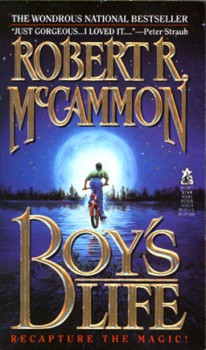

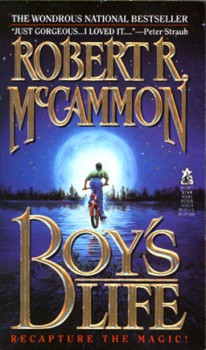

In the seventies and the eighties, Robert R. McCammon was a successful horror author. Usher’s Passing (a sequel to Poe’s classic), Wolf’s Hour (World War II werewolf yarn) and Swan Song (post-apocalyptic epic) were among his excellent works. 1990’s Mine was a different kind of terror tale, as was 1992’s Gone South.

To oversimplify, McCammon wanted to move out of horror and into new genres. And he was told to forget it: to not mess with the formula (shades of Brian Wilson and Pet Sounds). So he wrote two historical novels that weren’t published, and he quit.

A decade later, that first historical book, Speaks the Nightbird finally saw the light of day in 2002 and has spawned seven sequels and one short story collection. The next book is under way. I read the first two and enjoyed them. But they grow continually darker and I quit after book three. Too much for me.

McCammon has written a few other novels and novellas, back in the horror genre. But he returned on his own terms, and not with a major publishing house.

Two thousand is a low estimate of how many books I’ve read, and the single finest piece of writing I’ve ever come across is in the introduction to his 1991’s Boy’s Life. Which isn’t really too surprising, because that is the finest book I’ve ever read; in any genre. It’s not a horror book: it’s a coming-of age tale. It’s a book about the magic of our youth. And what happens to that magic.

One of my favorite authors, Tony Hillerman, said that Fly on the Wall, was his attempt at writing The Great American Novel. He feels he came up short. He would know, though it’s in my Top Five Novels list. But I’m gonna say that Boy’s Life is McCammon’s Great American Novel. And it’s in the running for THE Great American novel You ask me for only one book to read (beyond the Bible), and I’m telling you Boy’s Life.

Here’s the rest of that snippet from the opening that has stayed with me for going on three decades:

…

Read More Read More

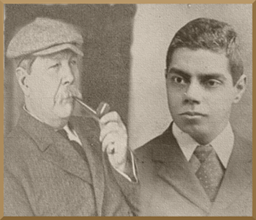

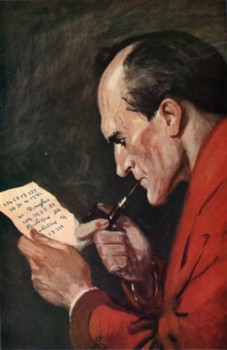

Back on September 29th of last year, I created a linked index of all The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes posts up to that date, plus a few extras that I’d written here at Black Gate. Well, since this column debuted on March 10, 2014 (yep, a year ago tomorrow!), I figured I’d create an index of all the posts written since that first index.

Back on September 29th of last year, I created a linked index of all The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes posts up to that date, plus a few extras that I’d written here at Black Gate. Well, since this column debuted on March 10, 2014 (yep, a year ago tomorrow!), I figured I’d create an index of all the posts written since that first index.