Clockwork Angels III. Hope is What Remains to be Seen

Today, July 1, is the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth anniversary of the date the British North America Act came into effect, which effectively established the modern country of Canada. We still celebrate that as our national holiday: Canada Day. So it’s only appropriate that I’m posting now about three men who have together been named as official Ambassadors of Music by the Canadian government, who have been made Officers of the Order of Canada, and who have as a group won the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award. I’m talking about Rush, and after two posts recapping their career (the first here, the second here), I’ll finally be writing about their new album, Clockwork Angels.

Today, July 1, is the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth anniversary of the date the British North America Act came into effect, which effectively established the modern country of Canada. We still celebrate that as our national holiday: Canada Day. So it’s only appropriate that I’m posting now about three men who have together been named as official Ambassadors of Music by the Canadian government, who have been made Officers of the Order of Canada, and who have as a group won the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award. I’m talking about Rush, and after two posts recapping their career (the first here, the second here), I’ll finally be writing about their new album, Clockwork Angels.

It’s a long album, over 66 minutes, and tells a single story. Although reminiscent of some of their older songs, not least due to lyricist Neil Peart’s use of themes and images that’ve clearly fascinated him for years, it’s also new ground for the band, who have never before created a fully-fledged concept album. Clockwork Angels is a steampunk epic in 12 songs, with accompanying passages of narrative prose that help to tie the story together. A novelization’s forthcoming in September by author Kevin J. Anderson, in collaboration with Peart.

To reiterate something I said in the first of these posts: this is a brilliant album. It’s lyrically and musically complex, constantly challenging, a treasure trove of ideas that’s impossible to assimilate in a single listen. The conceptual and narrative structure works, and lends the album a distinct feel — literally, a novelistic (and novel) sensibility. The relation of the songs, the recurrence of symbols that both resonate with the album’s story and derive from earlier in Peart’s career, gives Clockwork Angels significant thematic depth.

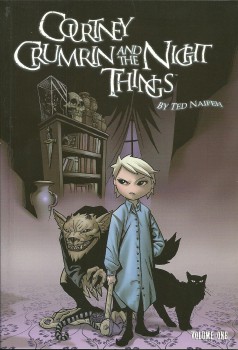

Be honest. If you had magical powers when you were a teenager, what would you have done? How long would you have walked the path of righteousness before cursing the school bullies? Before casting a spell to make yourself popular? Before just flat-out killing bad people? Would you have made friends with elves … or goblins?

Be honest. If you had magical powers when you were a teenager, what would you have done? How long would you have walked the path of righteousness before cursing the school bullies? Before casting a spell to make yourself popular? Before just flat-out killing bad people? Would you have made friends with elves … or goblins? Honeyed Words

Honeyed Words

Who would think at the start of the summer that Brave was concealing more of its plot and themes than

Who would think at the start of the summer that Brave was concealing more of its plot and themes than