In 500 Words or Less: The Language of Beasts by Jonathan Oliver

|

|

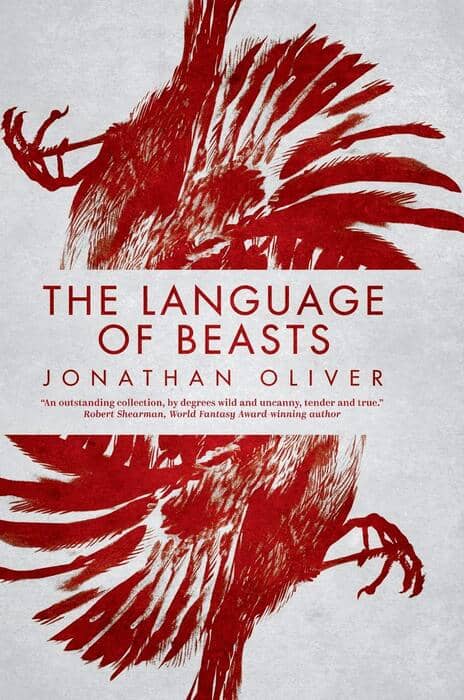

The Language of Beasts

By Jonathan Oliver

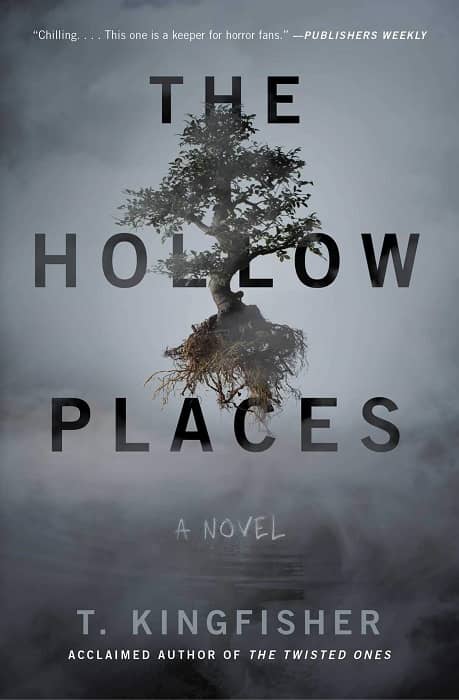

Black Shuck Books (392 pages, $25.99 hardcover, $8.99 eBook, October 1, 2020)

Cover by Simon Parr

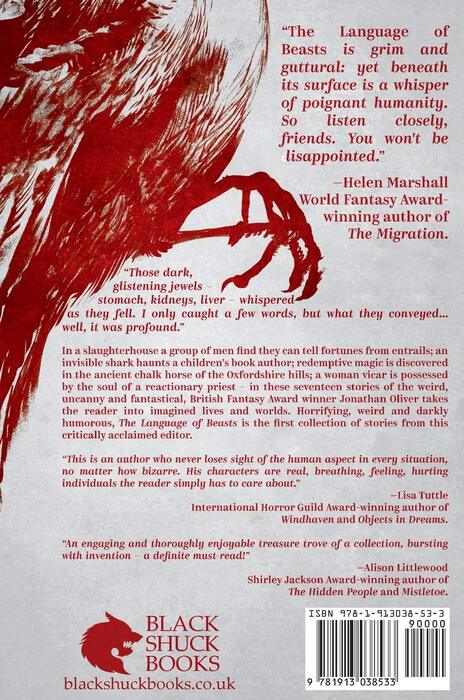

We’re approaching Halloween, so let’s talk horror and the weird! I was looking at earlier reviews of Jonathan Oliver’s debut collection The Language of Beasts and what I found interesting is how often it’s described as both horrific but heartfelt – keeping people up at night by speaking to our humanity. And it’s true. (All of it, Han.) There have been so many accolades already for this collection that I’m not even sure what else I can add, but I’ll try.

One of my issues with modern horror is how creators keep leaning into the freaky, bloody, disgusting parts of the genre, which isn’t my thing. Jon’s stories do the opposite; you could replace the horrific with something else “spec” and the core of the story would be the same. They’re about characters with deep backstories that affect their entire life; people facing some of the worst traumas imaginable, made worse because they’re experiences we know are too common. “Tea and Sympathy” starts with a young woman whose husband dies suddenly of a heart defect, and then leads to his spirit returning to her using men who are near death. The body-snatching and haunting isn’t the part that got to me: it’s the knowing that, at barely thirty-one, if something happens to me I would want to do everything in my power to make sure my partner was okay, even at the expense of the soon-to-be-deceased. That’s a startling realization to grapple with, but making you consider things like that is one of the most powerful aspects of Jon’s writing.