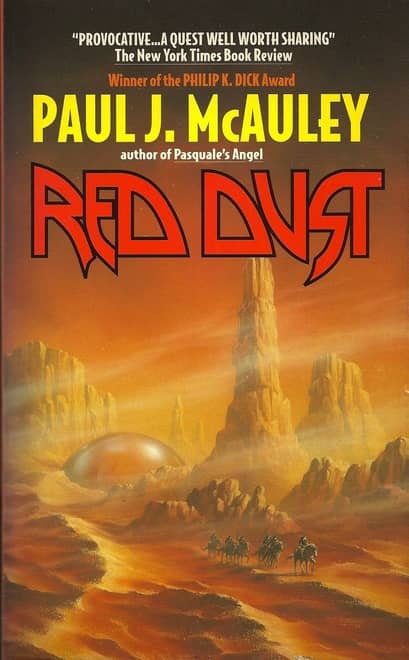

Vintage Treasures: Red Dust by Paul J. McAuley

|

|

Paul J. McAuley was the first book reviewer for Black Gate, way back in 2000-01. His first novel, the far-future space opera Four Hundred Billion Stars (Del Rey, 1988) won the Philip K. Dick Award, the sequels Of the Fall and Eternal Light appeared in 1989 and 1991.

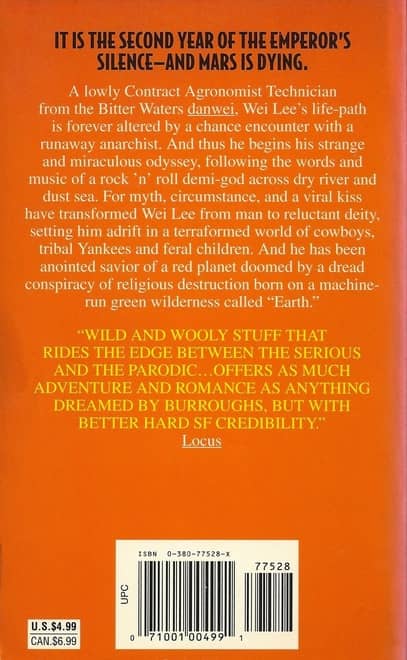

His first standalone novel Red Dust, set on a far-future Mars colonized by the Chinese, was published by Gollancz in the UK in 1993 and AvoNova in the US in 1995. It was packed with big ideas and technologies that are still being explored in SF today, including personality downloads, biotech, virtual reality, nanotech, A.I, and a lot more. Kirkus Reviews raved, saying:

An extraordinary saga.. Seven hundred years hence, a depopulated Earth is ruled by the Consensus eco-fanatics who allow nothing to change; on Jupiter, a self-aware probe calling itself the King of the Cats broadcasts rock music and propaganda; various dwindling groups of dissenters inhabit the asteroid belt; and Mars, habitable but slowly reverting to dust and drought and populated mostly by Chinese, is ruled by a committee of ruthless old men called the Ten Thousand Years, who, in a secret pact with the Consensus, have agreed to let Mars die in return for personal immortality. Young technician Wei Lee, who believes himself beholden to his great-grandfather, one of the Ten Thousand Years, stumbles upon a spaceship crashed in the dust… McAuley’s Mars is at once satisfyingly familiar and disquietingly alien: cultural contrasts, persuasive inventions, and constant surprises are set forth with a weird yet compelling logic. Superb.

The novel has never been reprinted in the US, but copies are still fairly easy to find online. I bought the brand new copy above on eBay for $4 two months ago. It was published by AvoNova in November 1995; it is 392 pages, priced at $4.99 in paperback. The cover is by Tim Jacobus. A digital edition was published by Gollancz/Orion in 2010. Our previous coverage of Paul J. McAuley includes his recent Choice Series and his Confluence novels.