Wings, Wind, and World-Wreckers: The Best of Edmond Hamilton

James McGlothin has been providing excellent continuing coverage on Black Gate of Del Rey’s famous “The Best Of…” anthologies that shaped many SF readers in the 1970s. He was kind enough to allow me to take a pile of notes I’d assembled for Del Rey’s The Best of Edmond Hamilton (1976) and do an entry in the series. I also sought the blessing of our editor John O’Neill because Edmond Hamilton is his favorite pulp author and I wanted to feel sure I wasn’t intruding too far into another’s territory. Both James and John are welcome to trash Edgar Rice Burroughs and Godzilla as much as they want after this.

James McGlothin has been providing excellent continuing coverage on Black Gate of Del Rey’s famous “The Best Of…” anthologies that shaped many SF readers in the 1970s. He was kind enough to allow me to take a pile of notes I’d assembled for Del Rey’s The Best of Edmond Hamilton (1976) and do an entry in the series. I also sought the blessing of our editor John O’Neill because Edmond Hamilton is his favorite pulp author and I wanted to feel sure I wasn’t intruding too far into another’s territory. Both James and John are welcome to trash Edgar Rice Burroughs and Godzilla as much as they want after this.

I’ll admit to having absorbed less Edmond Hamilton than I should. I’ve read some of his short fiction, but only one of his novels, The Star Kings (1947), a science-fiction variant on The Prisoner of Zenda that’s about as thrilling as Golden Age space opera gets. (Because John O’Neill will ask, I read the original magazine version of The Star Kings, not the later book revision with the sequel-friendly ending.) I’m more familiar with the work of Hamilton’s wife, Leigh Brackett, one of the great science-fiction writers and one of my favorite authors of all time. Their marriage didn’t lead to frequent collaborations, as the marriage of C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner did. I’m glad Hamilton and Brackett maintained separate writer identities, and the feeling became sharper after reading this selection of what Brackett thought was her husband’s finest short fiction.

I’ve read many of the Del Rey “Best Of…” volumes, but few that I’ve enjoyed as consistently as this one. It’s not only because Hamilton was a superb writer — all the authors in the series were first-rank SF masters — but because of two specific factors.

First, Hamilton’s career was sprawling. Not quite Jack Williamson immense, but it spanned the pre-Golden Age to beyond the New Wave. The deep well of stories from which the editor could pick meant it was impossible to force her to include anything mediocre. Even the least of the stories (“The Monster-God of Mamurth,” “Easy Money”) are worthy for a “Best Of” book.

Second, there’s the editor: Leigh Brackett, someone with special knowledge of the author and whose choices represents a personal interpretation rarely found in collections of any kind. Brackett even included a story she claimed to hate, “The Man Who Returned,” because of her visceral reaction to it. That’s something only a spouse could have done. I agree with Brackett: “The Man Who Returned,” the volume’s only non-speculative-fiction story, is a work of such cemetery misanthropy — a man accidentally entombed alive discovers everyone in his life prefers him dead — that I never want to read it again. That’s impressive.

A tone of bitterness and cynicism pervades many of the stories, which makes them stand out among other 1930s and ‘40s science fiction. What’s surprising is how often Hamilton’s early work upends genre assumptions of the time, such as the grand right of humanity to conquer other worlds and kill their bug-eyed inhabitants. Hamilton confronts space colonialism head-on in “A Conquest of Two Worlds,” only the third story in the volume and one of its best. Hamilton portrays Earth explorers as brutal conquerors who oppress the other races of the solar system in order to filch their resources. The protagonist is an Earthman who turns against his race — and his two childhood friends — to join the final stand of the Jovians. This is a gut-punch story for 1932, the sort of work that showed how advanced many SF concepts already were in the pre-Campbell era.

A tone of bitterness and cynicism pervades many of the stories, which makes them stand out among other 1930s and ‘40s science fiction. What’s surprising is how often Hamilton’s early work upends genre assumptions of the time, such as the grand right of humanity to conquer other worlds and kill their bug-eyed inhabitants. Hamilton confronts space colonialism head-on in “A Conquest of Two Worlds,” only the third story in the volume and one of its best. Hamilton portrays Earth explorers as brutal conquerors who oppress the other races of the solar system in order to filch their resources. The protagonist is an Earthman who turns against his race — and his two childhood friends — to join the final stand of the Jovians. This is a gut-punch story for 1932, the sort of work that showed how advanced many SF concepts already were in the pre-Campbell era.

This cynicism shows up in later stories, such as “After a Judgment Day” and “Requiem,” both taking place after human life no longer remains on Earth. According to Brackett, “Requiem” was a favorite of Hamilton’s, and it does have personalized feeling. A survey mission returns to an uninhabitable Earth for a final farewell before the planet plunges into the Sun. The mission commander develops an attachment to the dying world and becomes its sole mourner when everyone else in a mass media culture views the planet’s death as empty spectacle. Apocalyptic Earth also appears in “Day of Judgment,” although this Gamma World-style setting of mutated, intelligent animals delivers a note of hope when the new rulers of Earth show mercy to the ones who caused the original catastrophe.

The most disenchanted story is the collection lynchpin: “What’s It Like Out There?” Hamilton wrote this story in the early ‘30s, using the same pessimistic view of humanity’s mission to the stars found in “A Conquest of Two Worlds.” No magazine bought it at the time. Almost twenty years later, Hamilton re-wrote it and sold it at Brackett’s insistence. A man returning from the second Mars expedition covers up the depressing failures of the mission with the tales of optimism and faux-heroics his listeners want. What’s it really like out there? It’s awful and costing lives — all in the name of giving Earth a bit of hope and extra uranium. I understand why magazines in the 1930s balked at publishing such a caustic story that eats away at the image of space exploration as a plucky science adventure.

If I had to pick a favorite among the contents, “What’s It Like Out There?” would compete with “Child of the Winds,” “In the World’s Dusk,” and “He That Hath Wings,” which all have an elegiac tone fitting their magazine of first publication, Weird Tales. “In the World’s Dusk” shows the influence of Clark Ashton Smith; the necromantic events at the close of life on Earth would fit easily into Smith’s setting of Zothique. “He that Hath Wings” is a lyrical tragedy about a man born with bronze-hued wings who attempts to live without them for the sake of love. “Child of the Winds” is almost the Platonic ideal form of a Weird Tales story as it combines a pulp explorer yarn with strange fantasy and romance. The ending contains a lingering mystery that, for me at least, is what sets apart the “weird story” from other kinds of fantasy, science fiction, and horror.

I must make special mention of “The Man Who Evolved,” the second oldest story in the collection. By modern standards, this is a creaky tale about a super-science experiment going right while simultaneously going wrong. Most of the time it hovers in the hoary early-SF territory of “scientist explains things to other scientist.” But, it gained pride of place as the opening story in Isaac Asimov’s mammoth Before the Golden Age survey of early SF because it was the first story that stayed in Asimov’s long-term memory. John O’Neill also marks this as the story that hooked him into Hamilton, so there’s obviously something special about it. I’m partial to another mad scientist-explainer story, “Fassenden’s World,” where a scientist creates a micro-sized universe and insouciantly wrecks worlds and kills billions as he toys with them. (Edmond Hamilton was sometimes referred to as the “World Wrecker” by other SF writers because of stories like this and “Thundering Worlds,” where the planet Mercury is used as like a bowling-ball to attack a foe.)

I must make special mention of “The Man Who Evolved,” the second oldest story in the collection. By modern standards, this is a creaky tale about a super-science experiment going right while simultaneously going wrong. Most of the time it hovers in the hoary early-SF territory of “scientist explains things to other scientist.” But, it gained pride of place as the opening story in Isaac Asimov’s mammoth Before the Golden Age survey of early SF because it was the first story that stayed in Asimov’s long-term memory. John O’Neill also marks this as the story that hooked him into Hamilton, so there’s obviously something special about it. I’m partial to another mad scientist-explainer story, “Fassenden’s World,” where a scientist creates a micro-sized universe and insouciantly wrecks worlds and kills billions as he toys with them. (Edmond Hamilton was sometimes referred to as the “World Wrecker” by other SF writers because of stories like this and “Thundering Worlds,” where the planet Mercury is used as like a bowling-ball to attack a foe.)

If I could make a single change to The Best of Edmond Hamilton, it would be to defy Del Rey’s series design of arranging stories in chronological order. I’d flip the positions of the final two, so “The Pro” comes last rather than “Castaway.” Hamilton wrote “Castaway” to order for an anthology about Edgar Allan Poe. It’s an interesting trifle. “The Pro” is a bolder final statement: an old science-fiction writer examines the consequences of his career. The protagonist is an aging pulpster, modeled on Hamilton and other authors he knew from the Golden Age, who sees his futuristic ideas arrive in the present — but with consequences that tear him up emotionally. “The Pro” goes to the heart of the old saw that SF writers paved the way to future innovations. Maybe they did, maybe they didn’t — and if they did, was it something they wanted? In the case of the fictional “Pro,” the answer is an adamant no. The closing moments, where the author softly beats against a shelf of his books and whispers, “Damn you, damn you,” should have dropped the curtain on the collection. It’s a brutally personal moment for a science-fiction writer with a long career.

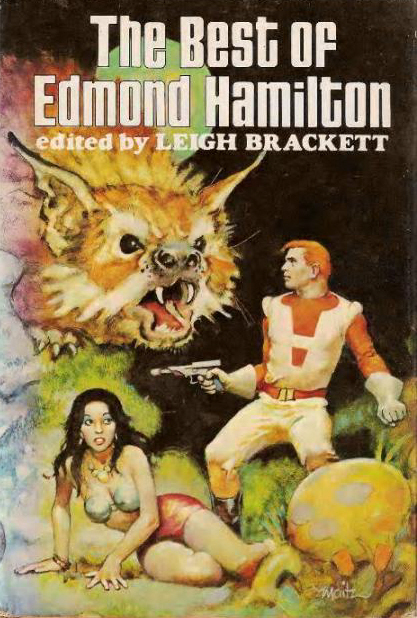

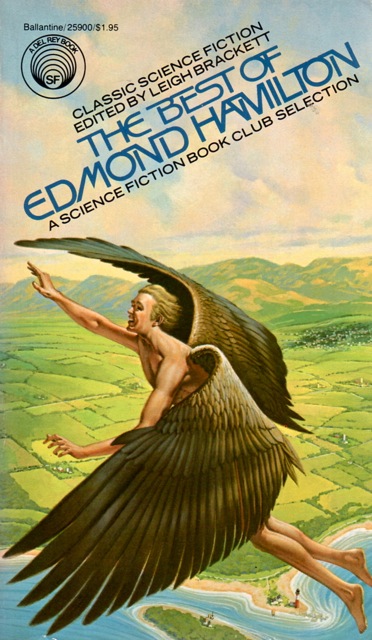

The Best of Edmond Hamilton was first published in April of 1977 in a Nelson Doubleday/SFBC hardback (cover art by Don Maitz), then in a Ballantine/Del Rey paperback in August (cover art by H. R. van Dongen). Hamilton died two months later. This adds a melancholy note to Brackett’s introduction, where she writes about the future great works her husband will create. However, because this collection arrived at the finale of Hamilton’s writing history, it makes an appropriate capstone. The Hamilton-edited The Best of Leigh Brackett was first published in July 1977. Brackett died eight months later. The two volumes are therefore a poignant dual farewell from a husband and wife celebrating each other’s lives and achievements. A husband and wife who were also two of the greatest science-fiction authors of all time.

The complete table of contents:

- Introduction: “Fifty Years of Wonder” by Leigh Brackett

- “The Monster-God of Mamurth” (Weird Tales, 1926)

- “The Man Who Evolved” (Wonder Stories, 1931)

- “A Conquest of Two Worlds” (Wonder Stories, 1932)

- “The Island of Unreason” (Wonder Stories, 1933)

- “Thundering Worlds” (Weird Tales, 1934)

- “The Man Who Returned” (Weird Tales, 1935)

- “The Accursed Galaxy” (Astounding Stories, 1935)

- “In the World’s Dusk” (Weird Tales, 1936)

- “Child of the Winds” (Weird Tales, 1936)

- “The Seeds from Outside” (Weird Tales, 1937)

- “Fassenden’s World” (Weird Tales, 1937)

- “Easy Money” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1939)

- “He That Hath Wings” (Weird Tales, 1938)

- “Exile” (Super Science Stories, 1943)

- “Day of Judgment” (Weird Tales, 1946)

- “Alien Earth” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1949)

- “What’s It Like Out There?” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1952)

- “Requiem” (Amazing Stories, 1962)

- “After a Judgment Day” (Fantastic Science Fiction, 1963)

- “The Pro” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1964),

- “Castaway” (The Man Who Called Himself Poe, 1968)

- Afterword by Edmond Hamilton

Our previous coverage of the Classics of Science Fiction line includes (in order of publication):

Smugglers, Alien Vampires, and Dark Dimensions: The Best of C. L. Moore

Rich Playboys, Mad Scientists, and Venusian Monsters: The Best of Stanley Weinbaum

Vampires, Frozen Worlds, and Gambling With the Devil: The Best of Fritz Leiber

Space Colonies, Interstellar Fleets, and The Martian in the Attic: The Best of Frederik Pohl

A Neglected Master: The Best of Henry Kuttner

A Shaper of Myths: The Best of Cordwainer Smith

The Best of Henry Kuttner

The Best of John W. Campbell

The Best of C M Kornbluth

The Best of Philip K. Dick

The Best of Fredric Brown

The Best of Edmond Hamilton

The Best of Murray Leinster

The Best of Robert Bloch

The Best of Jack Williamson

The Best of Hal Clement

The Best of James Blish

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

I need to find a copy of THE STAR KING, obviously in the original serial!

Yes, I think Hamilton’s cynical — or sorrowful — side shows up a lot in his shorter work particularly, as with “After a Judgement Day”.

I’ve got a copy of the July 1957 IMAGINATIVE TALES with “World of Never-Men” on the cover, right in front of me now. (Just by coincidence — I happened to grab that issue to take with me to Mesa on my current work trip.) I’ll get to that sometime soon!

@Rich, there is an in-print paperback edition of The Star Kings with the original magazine text from a little press called Armchair Fiction. It’s somewhat amateurishly produced as far as the text layout goes, but it is the original Star Kings. I think all the ebook editions are the 1960s rewrite, but John is probably the best person to ask about that.

> John O’Neill also marks this as the story that hooked him into Hamilton, so there’s obviously something special about it.

I haven’t had much success with adult re-reads of my teen SF idols. I still have an extraordinary fondness for pulp adventure, but virtually all the 1930s-era SF I’ve read or re-read in the last ten years has disappointed me. With the exception of Clark Ashton Smith, H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard…. and Edmond Hamilton.

I read “The Man Who Evolved” out loud to my kids a few years ago. I got still got chills, just I did when I first read it 40 years ago.

Great review RH! Given the tone of your review’s last paragraph, I think it would be fitting if you did the review of The Best of Leigh Brackett as well.

I’m almost done with Best of Kornbluth.

@James—Done! I’m thrilled to do Leigh Brackett’s collection as the companion piece. Plus… I kinda like Leigh Brackett.