Goth Chick News: The (Trend-Setting) House on Haunted Hill

House on Haunted Hill (Allied Artists, 1959)

In 2019 (aka “the Time Before”) one of the quintessential horror movies of our time celebrated its 60th birthday. The House on Haunted Hill (1959) starring Vincent Price, Carol Ohmart, Alan Marshal and Julia Mitchum was not only critically acclaimed in its own time, but still has an 88% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes today. Filmed for $200K over the course of 14 days in 1958, the film has netted over $1.5M and counting, thanks to video rentals and streaming. Ironically, its 40th anniversary remake in 1999, starring Geoffrey Rush and Famke Janssen cost $37M to make and has only netted $43M to date worldwide, making the original House proportionally the clear winner with fans.

What you may not know is the many ground-breaking elements of the film which still influence entertainment and promotion today. To start, director William Castle was the original master of guerilla marketing. His technique first appeared with his movie Macabre (1958) but due to its success, it was replicated with House a year later. Mr. Castle offered $1,000 Lloyd’s of London insurance policies for those brave enough to watch his horror film. However, if anyone with the policy by the died of fright during the movie, that person’s next of kin would be paid $1,000. In addition to this, Castle had select theater owners station nurses in their lobbies and park hearses outside. Castle himself said it was a shame no one actually expired during his movies as it would have been exceptional publicity. Today, directors such as J.J. Abrams (Super 8) and J.A. Bayona (Jurassic World; Fallen Kingdom) have taken such gimmicks even further to promote their films. Just Google the name of the movie and “guerilla marketing” to see the examples.

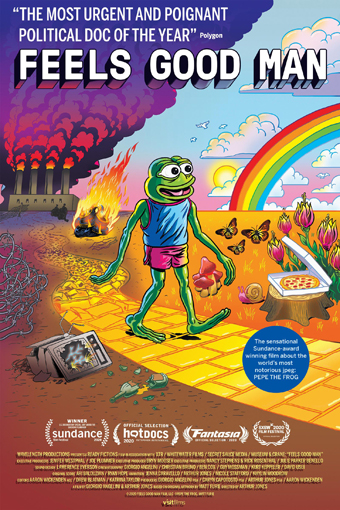

I try to keep an eye on comics, but like many people my first exposure to Pepe the Frog was as a poorly-drawn meme spouting racism. I remember reading about Pepe’s comics origin, but the name of Matt Furie, the cartoonist who created him, remained a piece of trivia. As did his comic Boy’s Club, where the frog first appeared. Now there’s a documentary telling the whole story of Furie, Pepe, and Boy’s Club — a tale of politics, appropriation, and how art can be used in ways the artist could not imagine, for worse and for better.

I try to keep an eye on comics, but like many people my first exposure to Pepe the Frog was as a poorly-drawn meme spouting racism. I remember reading about Pepe’s comics origin, but the name of Matt Furie, the cartoonist who created him, remained a piece of trivia. As did his comic Boy’s Club, where the frog first appeared. Now there’s a documentary telling the whole story of Furie, Pepe, and Boy’s Club — a tale of politics, appropriation, and how art can be used in ways the artist could not imagine, for worse and for better.  One of the genuinely wonderful things about covering a film festival is occasionally getting to be among the first audiences for a movie trying something new. That is, being an early viewer of a movie that does things unlike other movies, and getting to make one’s own mind up on whether those things work. Movies at a festival have often not had a critical consensus formed around them, and have not yet been defined by other writers or had their influences mapped out. You as the viewer are alone with the thing, almost contextless, in a way that’s rare these days.

One of the genuinely wonderful things about covering a film festival is occasionally getting to be among the first audiences for a movie trying something new. That is, being an early viewer of a movie that does things unlike other movies, and getting to make one’s own mind up on whether those things work. Movies at a festival have often not had a critical consensus formed around them, and have not yet been defined by other writers or had their influences mapped out. You as the viewer are alone with the thing, almost contextless, in a way that’s rare these days. Watching a film festival at home instead of in theatres raises a question that’s become a much-debated point over the last couple of years: is the experience of viewing a movie on a TV screen essentially different and essentially lesser than watching the same movie in a theatre? I don’t think there’s a single answer to this question. Different movies and different viewers and different circumstances will create better or worse scenarios. I think it is probably safe to say that the theatrical experience has much more sensory power; that the powerful sound system and the controlled environment and the full dark of a theatre will usually be more immediately overwhelming to a viewer. But it’s reasonable to wonder if a movie that relies on sheer sensory power can be called ‘a good movie.’

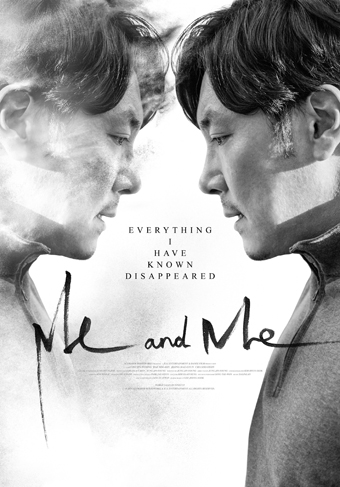

Watching a film festival at home instead of in theatres raises a question that’s become a much-debated point over the last couple of years: is the experience of viewing a movie on a TV screen essentially different and essentially lesser than watching the same movie in a theatre? I don’t think there’s a single answer to this question. Different movies and different viewers and different circumstances will create better or worse scenarios. I think it is probably safe to say that the theatrical experience has much more sensory power; that the powerful sound system and the controlled environment and the full dark of a theatre will usually be more immediately overwhelming to a viewer. But it’s reasonable to wonder if a movie that relies on sheer sensory power can be called ‘a good movie.’ Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) was one of the greatest samurai and greatest swordfighters ever to live. By his own account, he fought over sixty duels and won all of them. Stories about Musashi have been told and retold over the centuries, notably including the great novel Musashi (1935-39) by Eiji Yoshikawa. Films about him have proliferated, the most famous likely being Hirohi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-55) starring Toshiro Mifune as Musashi.

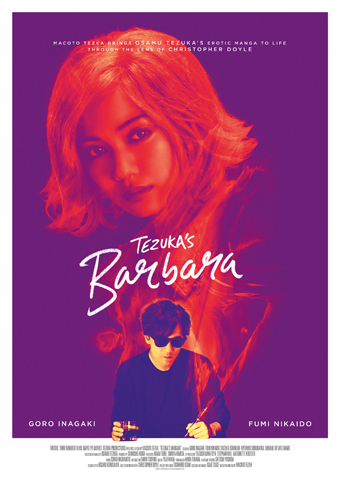

Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) was one of the greatest samurai and greatest swordfighters ever to live. By his own account, he fought over sixty duels and won all of them. Stories about Musashi have been told and retold over the centuries, notably including the great novel Musashi (1935-39) by Eiji Yoshikawa. Films about him have proliferated, the most famous likely being Hirohi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-55) starring Toshiro Mifune as Musashi. The chain of inspiration behind a work of art can be stunning to behold. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffman was a musician, critic, and fiction writer in the early nineteenth century whose surreal and gemlike short stories are wonders of early fantasy. Some of those stories were worked into the libretto of Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les contes d’Hoffmann. Adapted to films at least three times, most notably by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951, Offenbach’s work would inspire the great manga creator Osamu Tezuka in 1973. A

The chain of inspiration behind a work of art can be stunning to behold. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffman was a musician, critic, and fiction writer in the early nineteenth century whose surreal and gemlike short stories are wonders of early fantasy. Some of those stories were worked into the libretto of Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les contes d’Hoffmann. Adapted to films at least three times, most notably by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951, Offenbach’s work would inspire the great manga creator Osamu Tezuka in 1973. A  Day 6 of Fantasia 2020 started for me with a panel on folk horror. While you can find the

Day 6 of Fantasia 2020 started for me with a panel on folk horror. While you can find the

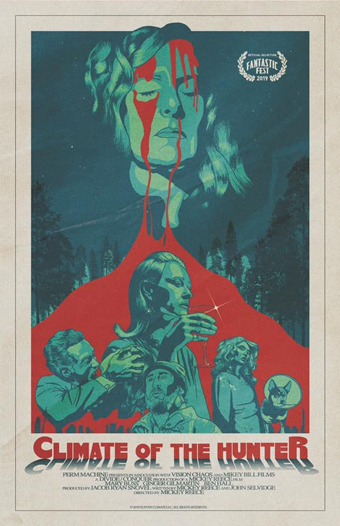

Mickey Reece is a musician turned underground filmmaker with over two dozen features to his credit. In 2019 he came out with Climate of the Hunter, which he directed and wrote with John Selvidge. It streamed on-demand at this year’s Fantasia Festival, and it’s billed as a cross between old-fashioned movie melodramas in the style of Douglas Sirk — what is sometimes called a “

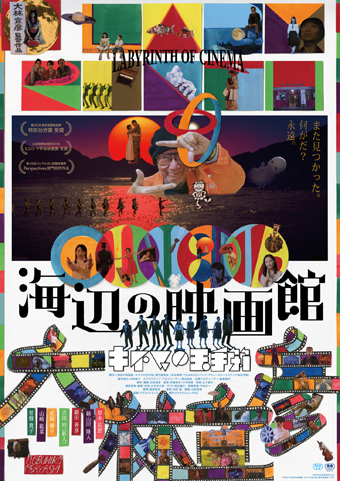

Mickey Reece is a musician turned underground filmmaker with over two dozen features to his credit. In 2019 he came out with Climate of the Hunter, which he directed and wrote with John Selvidge. It streamed on-demand at this year’s Fantasia Festival, and it’s billed as a cross between old-fashioned movie melodramas in the style of Douglas Sirk — what is sometimes called a “ Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.