Fantasia 2020, Part IX: Labyrinth of Cinema

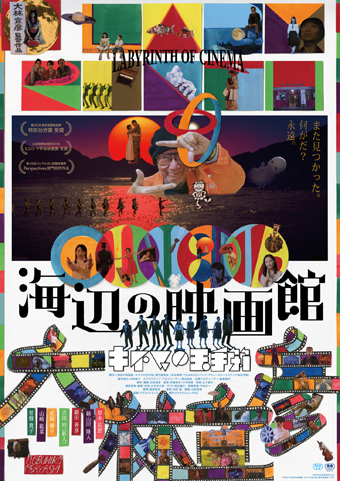

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

It begins in an almost essayistic manner, with the musings of a narrator named Fanta G (Yukihiro Takahashi), floating among memory fragments in a time machine that eventually brings him to the present day and the seaside city of Onomichi (Obayashi’s home). The last cinema in town will be closing at dawn, but before that happens an audience will take in one last picture show. And then some of members of that audience are caught up on the images onscreen — three young men chasing a mysterious teen named Noriko (Rei Yoshida).

The film ranges across the years roughly from 1868 to 1945, talking about Japan’s history, how it played out in film, and how Japanese film itself developed. The decline of samurai and the rise of mass mechanised warfare is seen through a peculiar lens, the garrulous Fanta explaining everything necessary as the film goes along. The characters from the audience take on different roles, playing out different stories across different genres and forms. If the frame concept of the Onomichi movie house is self-consciously surreal, the scenarios that incorporate the audience members grow more serious as the film goes on.

The movie begins with a blitz of images and ideas, introducing concepts at a furious pace to the point that ten minutes in I almost stopped taking notes. Not only do we get Fanta G’s time travelling, and then the cinema, and then an assortment of characters, but we’re told that the film will be referring to the writings of poet Chuya Nakahara (1907-1937), and soon get dance numbers and black-and-white scenes and title cards and even passages like silent film. And a visual approach seemingly based on collage, compositing together images like an odd kind of cartoon. Thankfully, it slows down, and in fact continues to slow as the film goes along. But not before a range of genres appears onscreen — musicals and yakuza films and samurai movies — somehow all coexisting.

Not all of Obayashi’s imagery is clear. For example, one of the audience members who gets drawn into the film is named Mario Baba (Takuro Atsuki), a reference to horror film master Mario Bava; why that director’s mentioned is obscure, at least to me. But then Obayashi plays wildly with film history, and in this Labyrinth of Cinema we also get to see Yasujiro Ozu and John Ford (played by Obayashi himself). As Obayashi arrays history and war on one side, and movies on the other, he draws in culture from every hand.

Not all of Obayashi’s imagery is clear. For example, one of the audience members who gets drawn into the film is named Mario Baba (Takuro Atsuki), a reference to horror film master Mario Bava; why that director’s mentioned is obscure, at least to me. But then Obayashi plays wildly with film history, and in this Labyrinth of Cinema we also get to see Yasujiro Ozu and John Ford (played by Obayashi himself). As Obayashi arrays history and war on one side, and movies on the other, he draws in culture from every hand.

The result is ludicrous but profound, and somehow not wearying. Partly that’s the pacing, blasting us with ideas and then slowing to let us put those ideas in an emotional and narrative context. Partly, maybe, it’s the look of the thing, the theatricality of it. Obayashi uses CG elements with a cheerful lack of concern for plausibility, making sure the artifice of the story’s front and centre, but the fakeness doesn’t make it any less affecting. It’s a movie about movies, and the weird plastic feel makes us notice the form even more.

A lot of the film’s power has to come from its themes — and how it dares explore deep and troubling aspects of human nature with a formal approach based on sheer implausibility. Labyrinth is able to use this eclecticism to present war as waste both through satire and, particularly in the slower second half, as tragedy. Thrilling adventures of samurai being made irrelevant by guns give way to corps of women and brigades of boys giving their lives for nothing in particular; and as war’s cost becomes clear, cinema and storytelling become correspondingly more important. Labyrinth shows us artists who make things real, who cannot stop war but who can tell stories about its pain.

Obayashi, who was born in 1938, has spoken and written about growing up in a militarised environment. For him, as we see in Labyrinth, film is a counterbalance to militaristic propaganda. It does seem to me that there’s a critique here that the movie’s discussion of militarism focusses entirely on what happens within Japan’s borders — there are scenes with Japanese soldiers in Manchuria, and there is an extensive section in the second half depicting the Japanese military occupying the Ryukyu Islands, but in general this is a discussion of militarism that does not deal with imperialism.

Obayashi, who was born in 1938, has spoken and written about growing up in a militarised environment. For him, as we see in Labyrinth, film is a counterbalance to militaristic propaganda. It does seem to me that there’s a critique here that the movie’s discussion of militarism focusses entirely on what happens within Japan’s borders — there are scenes with Japanese soldiers in Manchuria, and there is an extensive section in the second half depicting the Japanese military occupying the Ryukyu Islands, but in general this is a discussion of militarism that does not deal with imperialism.

On the one hand, that’s a large and surprising omission. On the other, I wonder if it doesn’t help focus the film, not just because it keeps its subject manageable, but because it allows Obayashi to discuss material more directly relevant to him and his experience. There is some autobiography in this film, or at least scenes presented as autobiography. And there is the sense of a work of art shaped by the sensibility and experience of its maker, a summing-up of the artist or a part of the artist.

It all cleverly ties together at the end. First by revealing a powerful double-meaning to the name of the old woman serving as the cinema’s projectionist, which links war and cinema. Then with a sort of cosmic zoom-out that explains the use of Fanta the narrator, a move that gives us the sense of scale, hammering home that the cinema builds a universe. Labyrinth of Cinema is an unlikely and daring creation, but it works. You can talk about alienation effects and about metafictions, you can talk about the extended sequences of realist narratives embedded within the frame, you can talk about a lot of things. But, put simply, this is a movie about movies that starts on the surface and moves deeper.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.