Fantasia 2020, Part VI: The Jesters: The Game Changers

I had a light schedule on the third day of Fantasia, as I tried to finish off some other business. But at 4 PM I sat down to watch the presentation of the festival’s Lifetime Achievement Award to John Carpenter. The ceremony was necessarily less than what it usually was, but the question-and-answer session that followed was rich and generous. I was particularly intrigued when Carpenter was asked about projects he regretted being unable to make, and he said that he’d tried to get Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination to screen but had been unable to get the script structure to work — and now suspects the book’s unfilmable. You can find the entire discussion here.

I had a light schedule on the third day of Fantasia, as I tried to finish off some other business. But at 4 PM I sat down to watch the presentation of the festival’s Lifetime Achievement Award to John Carpenter. The ceremony was necessarily less than what it usually was, but the question-and-answer session that followed was rich and generous. I was particularly intrigued when Carpenter was asked about projects he regretted being unable to make, and he said that he’d tried to get Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination to screen but had been unable to get the script structure to work — and now suspects the book’s unfilmable. You can find the entire discussion here.

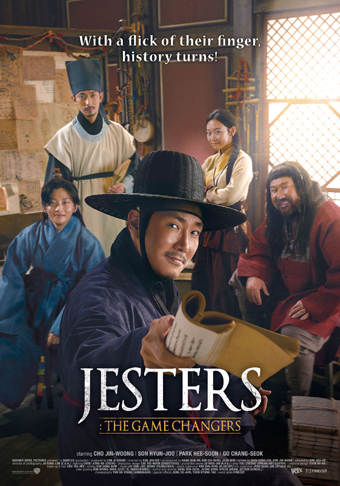

That evening I sat down to watch a Korean movie called Jesters: The Game Changers. Bundled with it was a short, “Yonorang” (작은 뼈), a visually stylish film directed by Kim Sangdong and written by Lee Sohyun. It’s a mostly dialogue-free story told in 8 minutes, incorporating monsters and swordfights and betrayal. The chronology’s fractured, too, and I found the relationship of the various scenes difficult to parse at one viewing. This is too bad, as it looks lovely (a little like Samurai Jack, but more stylised), and moment-by-moment the drama was palpable. I just couldn’t fit the pieces of the story together.

Jesters: The Game Changers (Gwang-dae-deul: Poong-moon-jo-jak-dan, 광대들: 풍문조작단) was directed by Kim Joo-ho from a script by Kim Jin-wook and Shin Jin-wook. It’s a somewhat-comic historical adventure story with fantasy touches set in the fifteenth century. King Sejo has usurped the country from his nephew and as the movie opens, all across the land jesters — wandering actors — are staging a popular play about the usurpation and the execution of six loyal ministers. Sejo orders the execution of the treasonous jesters, while his chief minister, Han Myung-Hee (Son Hyun-Joo) recruits a team of jesters of his own to present alternative facts and make the people believe that Sejo is the true anointed ruler.

The film follows the troupe as they alternatively propagandise for Sejo and then are alienated from the tyrannical monarch. The leader of the troupe, and the central character of the film, is Deok-ho (Cho Jin-woong, from, among other places, Kundo and Assassination), whose group includes an exiled painter (Yoon Park), a failed fortuneteller (Kim Seul-Gi), an acrobat (Kim Min-Suk), and a puppeteer (Ko Chang-Seok). They concoct incredible stage effects to simulate miracles, sometimes on vast scales, and the set-pieces the film gives us are structured around the inventive if improbable use of period technology to create these illusions. It’s not exactly clockpunk, in that the technology’s a step earlier than clockwork, but they do use things like magic lanterns — in devices that look surprisingly like modern movie projectors.

There’s a casual relationship here to actual history, but the important point is that the story works as an adventure piece. The theatrical miracles are clever, shown in enough detail that we understand how the jesters do what they do, without ever bogging the movie down in minutiae or self-indulgence. Crucially, the ‘miracles’ come at structurally significant points of the story, setting up plot elements and establishing character, as well as building to a major climax.

There’s a casual relationship here to actual history, but the important point is that the story works as an adventure piece. The theatrical miracles are clever, shown in enough detail that we understand how the jesters do what they do, without ever bogging the movie down in minutiae or self-indulgence. Crucially, the ‘miracles’ come at structurally significant points of the story, setting up plot elements and establishing character, as well as building to a major climax.

The humour’s more erratic. There’s probably either too much that’s too broad, or else too little. The movie’s not an outright comedy, using jokes to flavour the adventure instead of the other way around. But as it stands those jokes have a tendency to deflate the story, defusing tension. They’re a bit too obviously reassuring, too much a direct statement of what kind of story we’re seeing. If there were either more humour, or if it were used with a little more restraint, the movie might have been more gripping, funnier, or both. (The comedy’s also occasionally in poor taste — a running gag about a guy pissing himself, a fat joke to close the movie, stuff like that.)

Still, it doesn’t sap the momentum of the film, which is probably the important thing. The pacing’s always strong, occasionally slowing down for dramatic scenes, but usually maintaining a high energy that carries us through the complex plans of the jesters with wit and panache. The film also maintains a sense of tension, of things mattering; it opens with the execution of three rebel jesters, for instance, and so maintains a balance of comedy and danger as a good adventure story must. The plot’s engagingly varied, too, moving the troupe along a path of growing political awareness — first they work for the tyrant to save themselves, then things change, and all along there’s a good element of intrigue. The truth behind Sejo’s accession comes out slowly and effectively; which is to say backstory and exposition are worked into the plot in good dramatic fashion.

Character isn’t the most important thing in a story like this, but even so it’s the weak link of Jesters. Deok-ho comes across fine, which is necessary, but the other members of the troupe are merely sketched in. The fortuneteller’s arc in particular feels underdeveloped, while a subplot about one of the troupe quitting in disgust never quite lands because the character isn’t given the space to breathe. Even a bit about an old injury of Deok-ho’s never quite adds up to anything. It feels like there’s a scene or two missing, perhaps trimmed to get the running time down to 107 minutes.

Character isn’t the most important thing in a story like this, but even so it’s the weak link of Jesters. Deok-ho comes across fine, which is necessary, but the other members of the troupe are merely sketched in. The fortuneteller’s arc in particular feels underdeveloped, while a subplot about one of the troupe quitting in disgust never quite lands because the character isn’t given the space to breathe. Even a bit about an old injury of Deok-ho’s never quite adds up to anything. It feels like there’s a scene or two missing, perhaps trimmed to get the running time down to 107 minutes.

Still, what’s here is quite fine. The colour sense in particular is effective and helps carry the movie; set design, costumes, and so forth keep a constant visual interest, with the jesters given bright eye-catching clothing that sets them apart from the rest of their world. The visual tableaux they create are also almost otherworldly in their sheer spectacle. That’s appropriate for a movie about the power of movies — which is what this is, in an odd way.

The kinds of lights and projection techniques the jesters use make their miracles a form of the miracle of cinema. They create special-effects extravaganzas while living within one. And he point of that broader story is clear, that artists can and must tell the stories that matter to them; which may mean telling stories to anaesthetise the people’s discontent, or it may mean awakening them. Deok-ho’s particularly proud of his troupe being the only commoners who don’t obey the rules. So the film describes a conflict of two stories, one justifying Sejo’s reign and one critical of him, and the winner will not be which is truer but which is told better.

These ideas are always clear. This isn’t a terribly subtle movie. Neither is it one that’s mainly concerned with the weight of its themes. There’s enough there for you to chew on, enough for the movie to be able to say it’s about something more than just pretty pictures, and that’s enough. There’s value in a movie that fulfills the promises it makes, and Jesters does just that. It’s exactly the kind of movie it looks like it is, and exactly the kind of movie it wants to be.

These ideas are always clear. This isn’t a terribly subtle movie. Neither is it one that’s mainly concerned with the weight of its themes. There’s enough there for you to chew on, enough for the movie to be able to say it’s about something more than just pretty pictures, and that’s enough. There’s value in a movie that fulfills the promises it makes, and Jesters does just that. It’s exactly the kind of movie it looks like it is, and exactly the kind of movie it wants to be.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.