Are Some “Classics” Best Neglected?: Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier

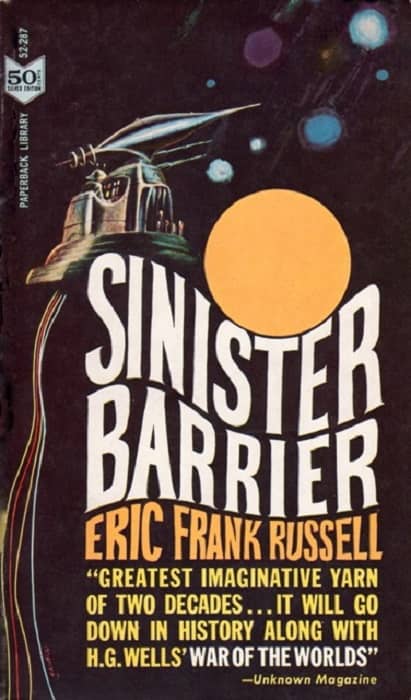

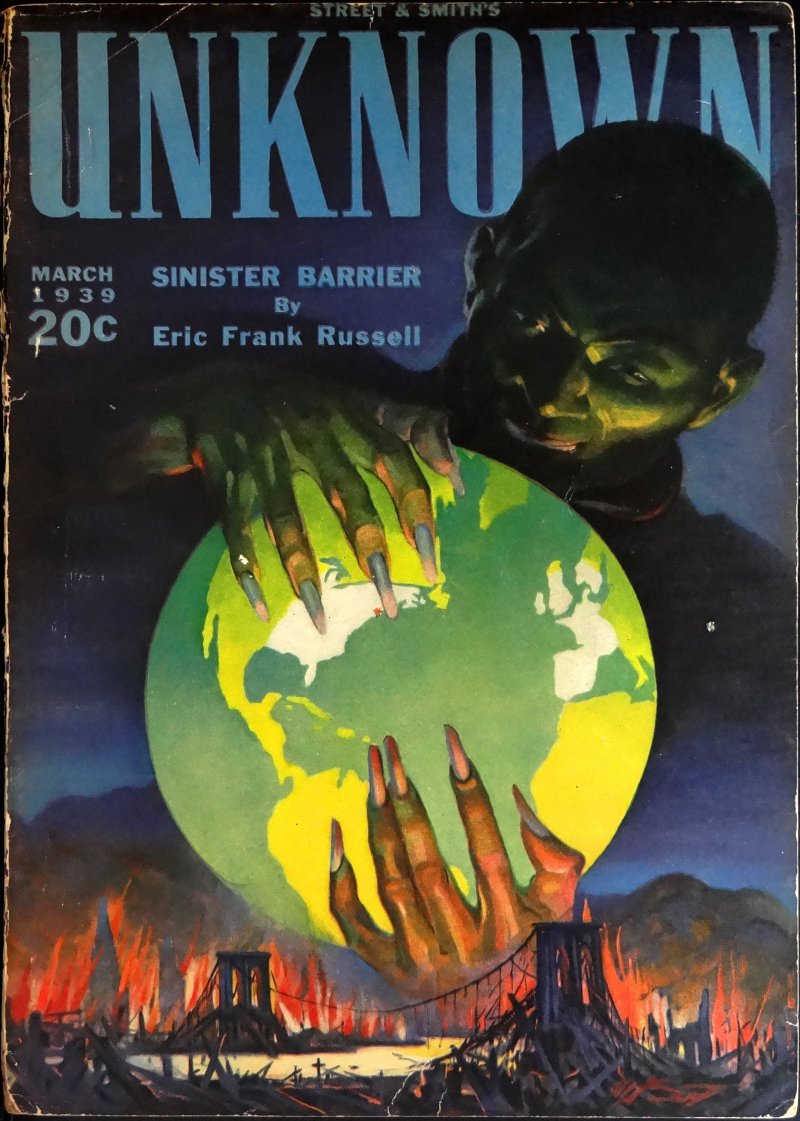

Sinister Barrier by Eric Frank Russell; Magazine version: Unknown, March 1939.

Cover art H. W. Scott. (Click to enlarge)

Sinister Barrier

by Eric Frank Russell

UK: World’s Work (135 pages, 5/-, hardcover, 1943)

US: Fantasy Press (253, $3.00, hardcover, 1948)

Here’s an early “classic” of science fiction that I came across in a used bookstore in Oakland early last year. I say “classic” with quotes because I had heard of the title for years, but hadn’t recalled ever seeing a copy. Indeed, the invaluable isfdb.com indicates that while it was included in an omnibus from NESFA Press in 2001, there hasn’t been a separate English language edition of the book since Ballantine Del Rey issued it in 1986, nearly 35 years ago. Hmm, why would this be?

Well, because it’s a terribly written book, dated both in language and in plotting and in its sexual and racial attitudes, exhibiting all the worst features of pulp writing, and far worse than the works of, say, Asimov and Heinlein that have survived from that era. That would be the reason modern publishers haven’t kept it in print. If it’s a classic in any way, it’s for its striking conceptual premise, and then only in its historical context. More on that in a bit.

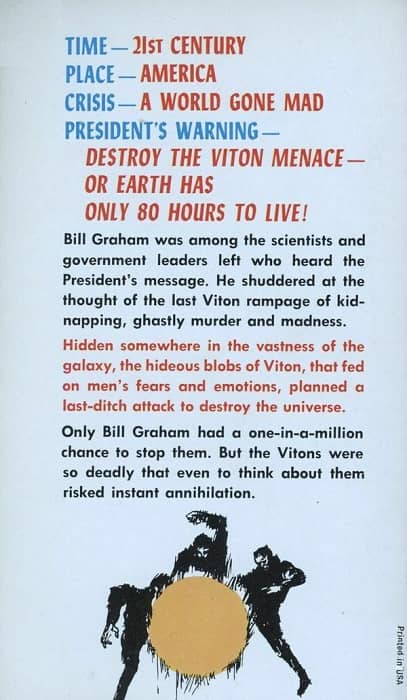

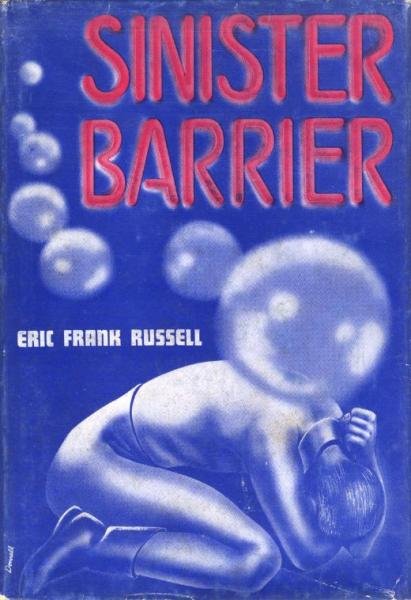

Sinister Barrier by Eric Frank Russell; World’s Work, 1943.

Cover art uncredited. (Click to enlarge)

Let’s set the context of the book first. Published as a book first in the UK by World’s Work in 1943, and then in the US by Fantasy Press in 1948 (the edition I found in the used bookshop, a library discard copy; see photos below), it had been serialized earlier in the very first, March 1939, issue of Unknown magazine, John W. Campbell’s fantasy companion to Astounding. In fact it was the lead story, featured on the cover, of that first issue, though it would come to be atypical of the magazine’s content; it was a straightforward science fiction story, in contrast to the more sophisticated fantasy content that the magazine became known for.

Just from reading the first few pages of this book, I had two immediate thoughts.

First, none of the encyclopedia entries for this book — e.g. SFE, Wikipedia — indicate how badly written it is, at least by modern standards. It’s awful, on a sentence by sentence basis. The prose is exaggerated, in a pulpish comic-book sense; words are used helter-skelter, with too many that don’t all go together in ways no careful writer would ever consider. Of course those encyclopedias rarely make comments, good or bad, about style or tone; their summaries are almost always limited to the work’s speculative content (and, at Wikipedia, to an extent, plot).

Second: thus, when we read about how “literary” critics of the 1950s and ‘60s sneered at science fiction as sub-literary trash, we have to admit that they were surely right in many cases. We can tell they could distinguish the better from the worse, as in the attitude “If it’s SF, it’s not good, if it’s good, it’s not SF” (first stated in so many words by Robert Conquest in one of his Spectrum anthologies). The counterpart of the critics’ attitude was that SF readers at the time apparently couldn’t tell the difference between better and worse, or simply didn’t care, since there were relatively few SF novels at the time, and they all needed to be supported. The first genre critics who did distinguish between the bad and the good were Damon Knight and James Blish, in their columns and reviews during the 1950s (later assembled into books); most infamously, Knight tore apart a popular work by A.E. van Vogt (another writer I have trepidation about revisiting).

So, to the book.

Gist

Alien beings manipulate and “own” humanity for nefarious reasons, which include feeding off human pain and anguish while at the same time shielding humanity from contact with other aliens. As famous scientists die or commit suicide, investigators pursue clues, in a wild romp with racist overtones, until a gizmo is invented to destroy the aliens.

Take

This is pulp SF, painful to read by any kind of contemporary sensibility, its theme an example of the kinds of conspiracy theories that have always, it seems, pervaded culture. The book is of historical significance, to scholars or to readers who prefer such writing, but cannot be recommended to most modern readers.

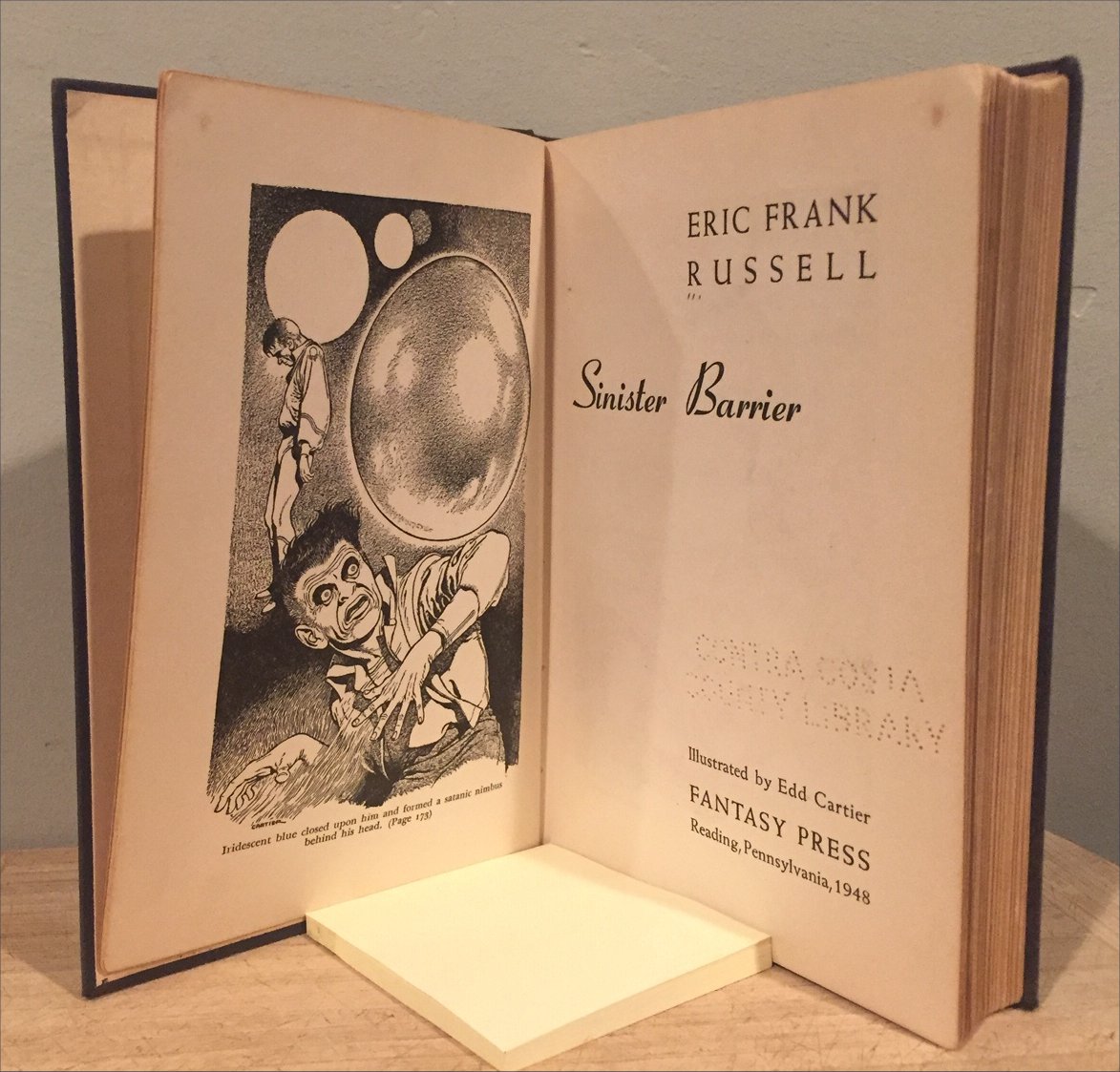

Sinister Barrier by Eric Frank Russell; Fantasy Press, 1948.

Cover art A. J. Donnell. (Click to enlarge)

Summary

Sinister Barrier claims its historical significance in SF history for its theme and for its popularity at the time. The 1948 Fantasy Press hardcover, perhaps because the earlier 1939 serial was already so well-known, even gives away the premise in the author’s foreword! Which is this: “we’re property.” That is, the human race is owned and manipulated by unseen beings, for their own purposes. And this explains how virtually every mysterious event you can think of from throughout history — and here Russell draws heavily on the work of Charles Fort (about whom Damon Knight wrote a book!) — can be explained as machinations of these unseen beings for the purpose of inciting violent emotions in humans, which is what these ethereal energy beings feed upon, or to prevent humans from detecting their existence. It’s the ultimate conspiracy theory SF novel: all sort of unrelated mysteries have a single explanation! A secondary premise of the book is that these energy beings may have cordoned Earth off from extraterrestrial contact, in effect saying “Keep off the grass.”

The story begins, in the year 2015, with a series of similar incidents in the early pages in which eminent scientists abruptly go mad and commit suicide. Bjornsen, Sheridan, Luther, then Mayo, who leaps out of a building, and Webb, who fires gun blasts at the wall of his office before collapsing. We eventually gather that they have detected or suspected parts of this unknown control of humanity. But the prose interrupts.

Page 5 (the first page of the novel, about Professor Peder Bjornsen):

Raising his hands, he pushed, pushed futilely at thin air. Those distorted optics of his, still preternaturally cold and hard, yet brilliant with something far beyond fear, followed with dreadful fascination a shapeless, colorless point that crept from window to ceiling. Turning with a tremendous effort, he ran, his mouth open and expelling breath soundlessly.

Page 7b, about Doctor Hans Luther:

Carrying his deceptively plump body at top speed across his laboratory, he raced headlong down the stairs, across the hall.

Deceptively? (And of course the grammar implies the carrying extends to the stairs and hall, despite the first phrase.)

Page 10.8:

Leaving the window open, he searched hastily through the papers littering the dead professor’s desk, found nothing to satisfy his pointless curiosity.

Pointless? I’d think his curiosity is entirely justified.

Page 26.8:

Wohl refrained from further comment while he concentrated on handling his machine. William Street slid rapidly toward them, its skyscrapers resembling oncoming giants.

The street is moving?

Several times, for example 12.2, we have this “said bookism” (if you’re not familiar with the term, see Turkey City Lexicon — A Primer for SF Workshops):

’What?’ ejaculated Graham.

Later, page 99b:

Whizzing high over jagged points of the Rockies which speared the red dawn, the pilot levelled off. Graham gaped repeatedly as he suppressed more yawns, stared through the plastiglass with eyes whose utter bleariness failed to conceal their underlying luster.

(I might mention that when I posted some of these samples on Facebook, I got a couple comments defending the prose as perfectly transparent, and better than the modern lit’ry stuff.)

|

|

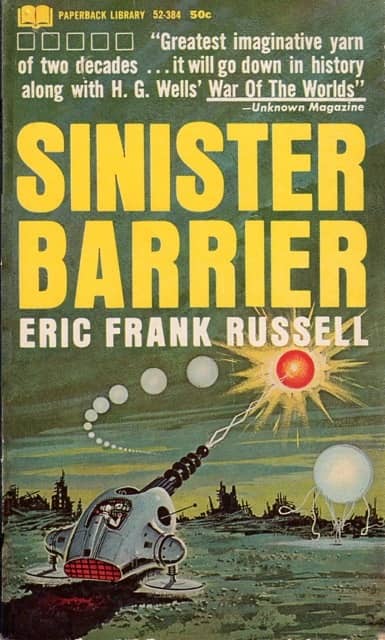

Sinister Barrier by Eric Frank Russell; Paperback Library, 1964. Cover by Jack Gaughan. (Click to enlarge)

OK then, this is antique, pulp SF. We already know the premise, How is it played out?

The story gets underway as a banker, Sangster — because his bank has funded Mayo and Webb in their research — assigns one of his men, Bill Graham – because, in a coincidence typical of pulp fiction, he witnessed Mayo’s suicide jump — to investigate. Graham teams up with a police investigator, Art Wohl, and the story has them follow lead after lead, at first to find other scientists who’ve committed suicide, then about the strange combination of iodine and other chemicals on their bodies, and to an asylum where the author indulges in some speculation about schizophrenics (p37). Graham is promoted to official government Intelligence, which entails him receiving an encoded identity ring. The next lead, about a Professor Beach in Silver City, Idaho, is frustrated by the abrupt destruction of the entire city.

The narrative alternates between car chases (with an extraordinary one in Chapter 2 about two-wheeled gyrocars outmaneuvering old four-wheel “jalopies” on a “skyway” accessed by a corkscrew ramp from the surface, with passengers pressed back and forth (long before anyone had thought of seatbelts), and gathering evidence that research into expanding the range of human visual perception — the “sinister barrier” of the title — has revealed previously unseen creatures perceptible only via infrared. (This was long before astronomers devised instruments to see IR, UV, etc.).

Pages 87-88:

The scale of electro-magnetic vibrations extends over sixty octaves, of which the human eye can see but one. Beyond that sinister barrier of our limitations, outside that poor, ineffective range of vision, bossing every man jack of us from the cradle to the grave, invisibly preying on us as ruthlessly as any parasite, are our malicious, all-powerful lords and masters—the creatures who really own the Earth!

(This is the one insight I give this story credit for: the realization that humans do not perceive everything there is to perceive. Cf. E.O. Wilson and others.)

Once this discovery is made; what to do? The unseen manipulators, whom someone dubs Vitons, trigger the “Asian races” to start a world war, and much chaos ensues.

Reflecting racist attitudes of his time, Russell posits that Asiatic races are especially susceptible to suicidal group thinking, as on page 49, with remarks about the Malaysians, the Japanese, the Hindus:

What was that subtle, unidentified essence in the human make-up which occasionally caused Malaysians to run amok, foaming at the mouth, kriss in hand, intent on wholesale and unreasoning slaughter? What other essence, similar but not the same, persuaded the entire nature of Japanese to view ceremonial suicide with cold-blooded equanimity? What make fanatical Hindus gladly cast themselves to death before the lumbering juggernaut?

This story-line is a version of the yellow peril theme unfortunately common in popular fiction of the early 20th century.

Then follow lots of scenes of bombings and mayhem, from the New York City setting. Later the Vitons abduct victims, rather than simply killing them, and return them to Earth as “dupes” (in a prefiguring of stories like Heinlein’s Puppet Masters and Finney’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers) to kill suspect humans. These Vitons are telepathic, you see, but only over short distances, and they can’t distinguish one human from another, only whether a human has perceived too much and is dangerous to them.

Various experts are gathered to work on weapons to destroy the Vitons, and because of the Viton’s limited range of perception, they work in underground labs. Their progress is statused in passages of technical jargon. This was an era of SF in which it was still possible to appeal to readers’ home-workshop understanding of optics or chemistry or radio electronics to justify the inventions the author imagines.

P201:

It was the iodine that made the difference. Methylene blue was the catalyst causing fixation of an otherwise degeneratable rectifier. He agreed that mescal served only to stimulate the optic nerves, attuning them to a new vision, but the actual cause was iodine.

P239:

Here, a worker bent over a true-surfaced peralumin disk and silver-plated it by wire-process metallization. While his electric arc sputtered its rain of minute drops, another worker close by plated another disk with granulated silver by-passed into an exoacetylene flame and thus blast-driven into the preheated surface. Any method would do so long as there was someone capable of doing it with optical accuracy.

Their efforts succeed, of course. The story ends as a method of destruction of the Vitons is discovered, and the world war evaporates.

The End.

Sinister Barrier by Eric Frank Russell; frontispiece and title page, Fantasy Press, 1948.

Illustration by Edd Cartier. (Click to enlarge)

Comments

Of course we can’t not notice the social and sexual attitudes of the era, as reflected in this book. (Yet another reason modern publishers would be very careful if reissueing a book like this.) There is a single female character in the book, a Dr. Harmony Curtis, introduced on page 22 as the half-sister of the deceased Webb, who is met with leers between Graham and Sangster. Then p24:

Dr. Curtis had a strict, professional air of calm efficiency which Graham liked to ignore. She had also a mop of crisp black curls and a curvaceousness which he liked to admire with frankness she found annoying.

Later, p76, Graham tries to distract himself from Viton detection by thinking of her.

He drew a woman from his memory, let his mind enjoy her picture, the curl of her crisp, black hair, the curve of her hips, the tranquil smile, which occasionally lit her heart-shaped face. Doctor Curtis, of course. Being male, he had no trouble in considering her unprofessionally. She’d no right to expert status anyway; not with a form like that!

No right!

The war over, Graham and Harmony conclude the story. There is a genuine insight here, about a change in the human condition:

“Up there, Harmony, are the stars,” he continued. “There may be people out that way, people of flesh and blood like us, friendly people who’d have visited us long ago but for a Viton ban. Hans Luther believed they’d been warned to keep off the grass. Forbidden, forbidden, forbidden—that was Earth.” He studied her again. “Every worthwhile thing forbidden, to those folk who’d like to come here, and to us who were imprisoned here. Nothing permitted except that which our masters considered profitable to themselves.”

“But not now,” she murmured.

“No, not now. We can emote for ourselves now, and not for others. At last our excitements are our own.”

This echoes any number of conceptual breakthrough events in SF, in which the true nature of reality becomes available.

The final page quickly closes to a budding romance. (I’ve read titles by E.E. Smith and Hugo Gernsback from this era that ended in actual marriage!)

“Has it struck you that in the truest sense we’re now alone?”

“We–?”

“Her face turned toward him, her eyebrows arched.

“Maybe this isn’t the place,” he observed, “but at least it’s the opportunity!” He bent her across his lap, pressed his lip on hers.

She pushed at him, but not too hard. After a while, she changed her mind. Her arm slid around his neck.

The End.

|

|

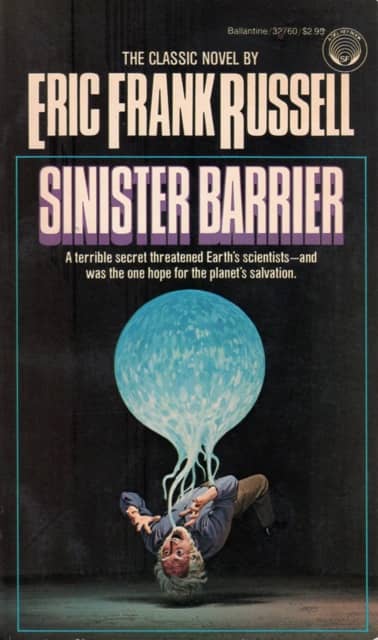

Paperback editions: Paperback Library, 1966 (artist unknown), Del Rey/Ballantine, 1986 (Ralph McQuarrie)

Conclusions

I have some general conclusions, not about this book so much as about how to approach “classic” science fiction works.

There’s some debate recently about the “canon wars,” which I don’t want to address directly but about which these comments may apply.

First, it’s obviously not true that the early, time-honored “classics” of science fiction are better than works by current writers who supposedly don’t realize they are reinventing classic SF ideas. While it’s true that in science, no one would get points for re-discovering relativity, say, science fiction isn’t science, it’s more of an art, and in art the same ideas can and often need to be reinterpreted anew by each generation.

Second, these time-honored “classics” of science fiction still exist, and can be respected, in their historical context. They should not be dismissed; they should not be “cancelled” in the manner of the current “cancel” culture; they should be respected as artifacts of their time, even if they may be of interest only to readers with historical perspective rather than casual readers who mightn’t appreciate those historical contexts.

And third, it’s worth recognizing that, not just science fiction history, but the history of particular authors, show extreme ranges of quality and context, moreso I suspect than typical mainstream authors. The book discussed here was an early Russell work. Isaac Asimov, in his earliest stories beginning around the same time, 1939, exhibited pulpish prose tendencies that he left behind within a few years. John Brunner and Robert Silverberg come to mind as writers whose early novels bore little resemblance to their later mature works.

Addendum

On this same theme, I perhaps inadvisably announced on Facebook, a week and half ago, that the next book I would review for Black Gate would be Edgar Pangborn’s West of the Sun. I chose it because Pangborn is an historically significant author, and West of the Sun was his first novel, and it along with a couple later works had been issued in handsome new hardcover editions by Old Earth Books beginning in 2001, which publisher Michael Walsh had kindly sent me.

Alas, I got through about a third of the book, and found it too much work to read. Because of prose. To put the nicest spin: it strikes me as amateur. Too many sentences with semicolons; confusing pronoun references; non sequiturs from one paragraph to the next; italicized inner thoughts of one character or another often in 1950s vernacular; and by 1/3 of the way in, too many aliens terms and names to keep track of. I bailed. Which I rarely do for any work of fiction.

And yet — Pangborn went on to write Davy and The Company of Glory, which I read years ago. I suspect that, like Asimov, like Russell, Pangborn learned to write better as his career progressed. His 1955 novel, A Mirror for Observers, won the International Fantasy Award! So I’ll try that one next.

A previous version of this review appeared at Views from Crestmont Drive in January 2019.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Chad Oliver’s The Winds of Time. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

I don’t tie myself in knots about the social sins of dead writers; as L.P. Hartley said, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” But Sinister Barrier is a very hackneyed piece of prose. I never found Russel’s snappy, faux-American tough guy diction at all convincing.

Supposedly SINISTER BARRIER was the reason Campbell founded UNKNOWN. He wanted to publish it, didn’t think it was really Science Fiction.

As for Pangborn — I haven’t read WEST OF THE SUN. But A MIRROR FOR OBSERVERS is wonderful. (It’s the book that should have won the Hugo that “They’d Rather Be Right” won (assuming you ignore THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING.)) And while WEST OF THE SUN was Pangborn’s first SF novel, he had published a mystery novel before, way back in 1930, as by “Bruce Harrison”.

Are you reading this because Alec Nevala-Lee has an incredibly high opinion of it?

https://nevalalee.wordpress.com/2016/04/07/astounding-stories-4-sinister-barrier/

In a later entry he said it’s his single favorite science fiction novel!

No, though I do remember his comment about the book in his own 2019 book about Campbell, et al; I have to wonder if he’s read the book recently. If he’s sincere, then for me this casts into doubt all his other opinions.

Thomas Parker pretty much wrote what I was thinking. Tried to read this book three times, found it an unpleasant slog.

On the other hand, I found Russell’s WASP to be quite entertaining.

Mark, thanks for the signpost, will avoid that route.

Another excellent review.

I settled down to read Sinister Barriers when I got the Selected Novels of EFR. That would have been sometime in the last ten years, I think. I can’t remember ever being so underwhelmed by a piece of pulp-era fiction. I guess if Unknown really owed its existence to this novel, I’m glad the novel was written. But, sheesh.

Of the Russell novels I’ve read, only Wasp really stands out, and even it is a tad long for the point it has to make. EFR was best at shorter lengths, I think.

Mirror for Observers I remember as being pretty good, though; I look forward to your review of that.

Has anyone noted the similarities of SINISTER BARRIER and Liu Cixin THREE BODY PROBLEM. Not a comparison of literary quality, but in terms of plot and themes.

I came here because I just read the plot and immediately thought of 3 body problem and googled to see if anyone else made that connection

Had read Liu’s “Ball Lightening” and in the midst of reading Sinister Barrier.Both involve the the use of ball lightening to disguise the presence of an alien race amongst earthlings.Can’t be a coincidence!

To be specific, Spectrum II: A Second Science Fiction Anthology (anth 1962), Robert Conquest:

“Sf’s no good,” they bellow till we’re deaf.

“But this looks good.” – “Well then, it’s not sf.”