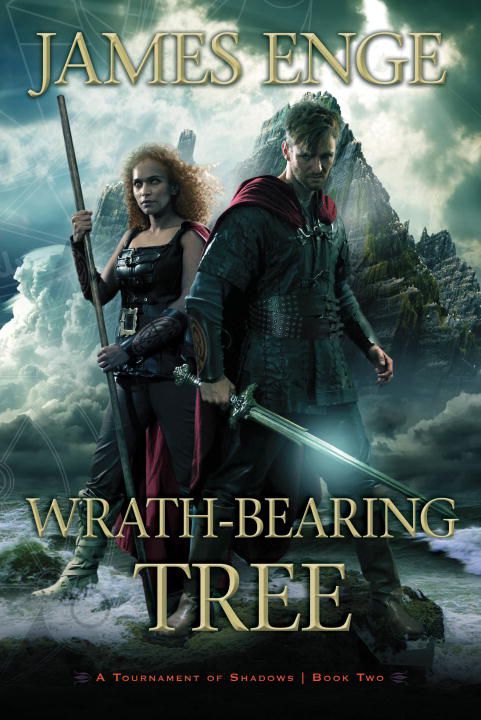

Wrath-Bearing Tree by James Enge

The first time I saw a James Enge novel on the shelf of my local bookstore, I broke into a little dance of jubilation. I’d been reading Enge’s short stories about Morlock the Maker in the pages of Black Gate — this was when BG had literal paper pages — and it was news to me that Enge had made the leap from short fiction to novels.

The first time I saw a James Enge novel on the shelf of my local bookstore, I broke into a little dance of jubilation. I’d been reading Enge’s short stories about Morlock the Maker in the pages of Black Gate — this was when BG had literal paper pages — and it was news to me that Enge had made the leap from short fiction to novels.

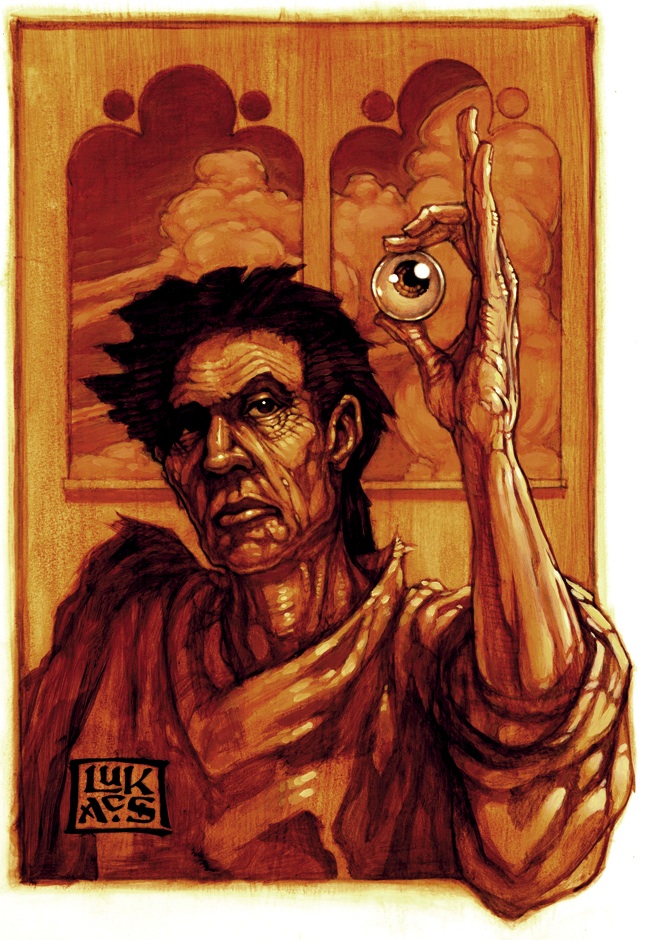

The blurbs on Enge’s books all say some variation on this theme: you will find no other character in fantasy literature, or maybe in literature generally, who is like Morlock the Maker. He’s a traumatized combat veteran who’s still one of his world’s great ass-kickers, yet he’s also an enthusiastically geeky mad scientist. He’s a cynic who will risk all he has to protect innocence where he finds it. He’s wickedly funny, in fewer words of dialogue than should really be possible. Read around in Morlock’s world a while, and you feel pretty soon like you know him, but you can never guess what he’ll do next. A Morlock novel! Could anything be better?

Over the next few years, Enge followed Blood of Ambrose with This Crooked Way and The Wolf Age, and it turned out the one thing better than a Morlock novel was a whole trilogy of Morlock novels.

Over the next few years, Enge followed Blood of Ambrose with This Crooked Way and The Wolf Age, and it turned out the one thing better than a Morlock novel was a whole trilogy of Morlock novels.

I loved the cranky old Morlock, the character whose curmudgeonliness sometimes verged on becoming a superpower, so I am still getting used to Enge’s new Tournament of Shadows trilogy about Morlock’s origin story, which began with A Guile of Dragons and now continues with Wrath-Bearing Tree. As a young man, our hero is every bit as odd, unpredictable, noble, hilarious, tragic, clear-eyed, and difficult as his future self, but he hasn’t yet put the damage on and become the ugly old man we loved in the short stories that became This Crooked Way.

I’ve always had a fascination with Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis that I’ve never been able to explain. Obviously, it’s a visually powerful film and a tremendous influence on

I’ve always had a fascination with Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis that I’ve never been able to explain. Obviously, it’s a visually powerful film and a tremendous influence on