New Treasures: The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker

I always find it interesting when mainstream publishers like Putnam, Harper, and Grove Press decide to publish a fantasy novel. Usually they do it badly, producing something that both fantasy fans and the general public scorn. Every once in a while they hit a home run, though — as Pocket did with Mark Helprin’s Winter Tale, for example, one of the most cherished fantasy novels of the 80s, or Grove Press accomplished just last year with G. Willow Wilson’s Alif the Unseen, which won the World Fantasy Award in October.

I always find it interesting when mainstream publishers like Putnam, Harper, and Grove Press decide to publish a fantasy novel. Usually they do it badly, producing something that both fantasy fans and the general public scorn. Every once in a while they hit a home run, though — as Pocket did with Mark Helprin’s Winter Tale, for example, one of the most cherished fantasy novels of the 80s, or Grove Press accomplished just last year with G. Willow Wilson’s Alif the Unseen, which won the World Fantasy Award in October.

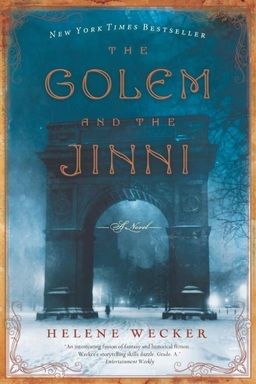

So I was intrigued enough to plunk down 15 bucks for Helene Wecker’s first novel, The Golem and the Jinni, a literary fantasy that blends Jewish and Arabian folklore in a tale of a chance meeting between two mythical beings in turn-of-the-century New York. The reviews have been kind, and it seems to be achieving a measure of early success.

Chava is a golem, a creature made of clay, brought to life to by a disgraced rabbi who dabbles in dark Kabbalistic magic and dies at sea on the voyage from Poland. Chava is unmoored and adrift as the ship arrives in New York harbor in 1899. Ahmad is a jinni, a being of fire born in the ancient Syrian desert, trapped in an old copper flask, and released in New York City, though still not entirely free.

Ahmad and Chava become unlikely friends and soul mates with a mystical connection. Marvelous and compulsively readable, Helene Wecker’s debut novel The Golem and the Jinni weaves strands of Yiddish and Middle Eastern literature, historical fiction and magical fable, into a wondrously inventive and unforgettable tale.

The Golem and the Jinni was published by Harper Perennial on December 31, 2013. It is 512 pages, priced at $15.99 in trade paperback and $10.99 for the digital edition.

See all of our recent New Treasures articles here.